Page last updated: February 2024

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Head and Neck Cancers - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2024 edition). This webpage was last updated in February 2024.

Expert content reviewers:

This information is based on international and Australian clinical practice guidelines for head and neck cancers. It was developed with the help of a range of health professionals and people affected by head and neck cancer:

- A/Prof Martin Batstone, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon and Director of the Maxillofacial Unit, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD

- Polly Baldwin, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA

- Martin Boyle, Consumer

- Dr Teresa Brown, Assistant Director Dietetics, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Honorary Associate Professor, University of Queensland, QLD

- Dr Hayley Dixon, Head, Clinical Support Dentistry Department, WSLHD Oral Health Services, Public Health Dentistry Specialist, NSW

- Head and Neck Cancer Care Nursing Team, Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC

- Rhys Hughes, Senior Speech Pathologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Dr Annette Lim, Medical Oncologist and Clinician Researcher – Head and Neck and Non-melanoma Skin Cancer, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Dr Sweet Ping Ng, Radiation Oncologist, Austin Health, VIC

- Deb Pickersgill, Senior Clinical Exercise Physiologist, Queensland Sports Medicine Centre, QLD

- John Spurr, Consumer

- Kate Woodhead, Physiotherapist, St Vincent’s Health, Melbourne, VIC

- A/Prof Sue-Ching Yeoh, Oral Medicine Specialist, University of Sydney, Sydney Oral Medicine, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW.

Treatment for head and neck cancer is often difficult both physically and emotionally, and it will take some time to recover. Side effects can be temporary, long-lasting or permanent, and some will need ongoing management and treatment.

Talk to your treating team for more information and support.

Your guide to best cancer care

A lot can happen in a hurry when you’re diagnosed with cancer. The guide to best cancer care for head and neck cancer can help you make sense of what should happen.

It will help you with what questions to ask your health professionals to make sure you receive the best care at every step.

Read the guide

Common side effects

Mouth problems

Some head and neck cancer treatments can cause mouth sores, ulcers and saliva changes. These problems can make eating difficult, but there are ways to manage them.

Mouth sores and ulcers

Mouth sores and ulcers are a common side effect of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. This is known as oral mucositis. The sores can form on any soft tissue in your mouth and make eating, swallowing and talking difficult.

This is usually short term and goes away as you recover from treatment. Your doctor can give you medicines to reduce the pain when you eat, drink or speak.

Your speech pathologist and dietitian can suggest foods to reduce discomfort. You may need to choose softer foods and nourishing fluids.

If you are unable to eat and drink enough to stay well nourished, you may need a feeding tube to support you during treatment and recovery.

Dry mouth and saliva changes

Radiation therapy to the head or neck area and surgery that affects the salivary glands can reduce the amount of saliva in your mouth, make your mouth dry or make your saliva thick and sticky. This is known as xerostomia and it is often long-lasting.

Xerostomia can make chewing, swallowing and talking difficult. A dry mouth can also make it harder to keep your teeth and mouth clean, which can increase the risk of tooth decay.

Fatigue

Fatigue for people with cancer is different from tiredness, as it may not go away with rest or sleep.

It is common to feel very tired during or after treatment, and you may lack the energy to carry out day-to-day activities.

For some people, fatigue continues for months or years after treatment ends.

Learn more

Taste, smell and appetite changes

Having treatments to the head, neck and mouth area may affect your sense of taste and smell.

Some treatments can change the way the salivary glands work and affect the flavour of food. It is important to try to keep eating well so your body gets enough nourishment.

Try experimenting with different textures, temperatures and presentations to make food more enjoyable. You could also try to do distract yourself by watching TV or reading a book while eating.

It can take several months for your sense of taste and smell to return to normal, and this may affect your appetite. A speech pathologist may be able to teach you a technique to help you regain your ability to smell.

In some cases, taste changes may be permanent.

Swallowing difficulties

Chewing and swallowing involves your lips, teeth, tongue and the muscles in your mouth, jaw and throat working together.

Many people with a head and neck cancer have difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) before, during or after treatment, which may be short term or long term.

Being able to swallow is important to ensure you are eating and drinking enough. Signs that swallowing is difficult include:

- taking longer to chew and swallow

- taking longer to eat a meal than your family and friends

- coughing or choking while eating or drinking

- food sticking in your mouth or throat

- pain when swallowing.

Treatment that may cause swallowing difficulties

- Surgery to the jaw, mouth or throat areas – this may make chewing and swallowing difficult because tissue has been removed or reconstructed, or because the surgery has caused dry mouth.

- Surgery to the larynx or pharynx – surgery to the larynx or pharynx may cause food to go down the wrong way into the lungs. This is known as aspiration and signs include coughing during or after swallowing, increased shortness of breath during or after a meal and recurrent chest infections.

- Radiation therapy – this can cause dry mouth, pain, and changes to the strength of the muscles and nerves used in swallowing. These effects could be worse if you have chemotherapy at the same time as radiation therapy (chemoradiation).

Swallowing test

You may have a test before and after treatment to look at what happens when you swallow. A speech pathologist uses a movie-type x-ray known as a videofluoroscopic swallow study or modified barium swallow study to check that foods and liquids are going down the correct way.

You may also have a test called a fibre-optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing during a nasendoscopy to see how well you can swallow. The test results will help the treatment team plan how any swallowing issues are treated.

How to eat when swallowing is difficult

- See a speech pathologist for ways to change your chewing and swallowing action to help reduce discomfort or food going down the wrong way (aspiration). They can also show you swallowing exercises, ways to change your posture and how to adjust the consistency of food to make it easier to swallow.

- Continue to eat and drink whenever possible throughout your treatment to keep your swallowing muscles moving and working. This will reduce the likelihood of long-term swallowing problems.

- Ask your doctor to recommend medicines that relieve discomfort when swallowing. Some of these medicines come as mouth rinses.

- If it is hard to swallow fluids without choking, a speech pathologist can advise ways to thicken supplement drinks.

- Talk to a dietitian to make sure you are getting enough nutritious food and drink.

- See the recipes in two free online books from Griffith University – From Treatment to Table and Beyond the Blender: Dysphagia Made Easy.

Using a feeding tube

As a result of surgery or radiation therapy, you may find eating and swallowing uncomfortable or difficult. A feeding tube may be inserted either before, during, or after your surgery or radiation therapy to help you get the nutrition you need. This tube is usually temporary, but sometimes it is permanent.

It is important to avoid losing a lot of weight during treatment and to have enough kilojoules and fluids. If you can’t swallow medicines, check with your doctor, nurse or pharmacist whether these can also be given through the feeding tube.

Your health care team will explain how to:

- care for the tube to prevent it leaking or becoming blocked

- avoid infections – this may include washing your hands before using the tube, and keeping the tube and your skin dry

- monitor for signs that the tube needs to be replaced

- handle issues such as what to do if the tube falls out – while this is very rare it is important to let your treatment team know immediately if this happens

- ensure the tape is secure, especially after a shower – if it’s not secure, the tube can be accidentally bumped out of place.

If you have a feeding tube, it is still important to brush your teeth and keep your mouth clean even though you are not eating or drinking.

The thought of having a feeding tube can be frightening, and it is common to have a lot of questions. Getting used to a feeding tube takes time. Talking to a dietitian or nurse can help, and a psychologist or counsellor can provide emotional support and suggest ways to cope.

Types of feeding tubes

Temporary feeding tube

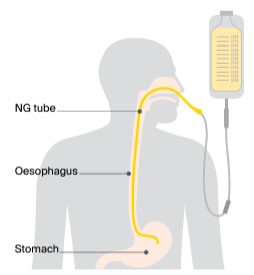

A thin tube is put into a nostril, then down the throat and oesophagus into the stomach. This is called a nasogastric or NG tube. It is mostly used if you need a feeding tube for a short time (e.g. the days or weeks after surgery when you can’t eat).

A doctor may put in an NG tube during an operation when you are asleep or a nurse or doctor may put in or remove the NG tube while you’re awake. A spray is usually used to numb the area to make it less uncomfortable to insert the tube. You will be given specially prepared liquid nutrition through this tube.

Long-term or permanent feeding tube

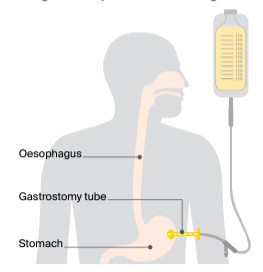

A tube is inserted through a hole in your belly into the stomach. This is called a gastrostomy tube. It may be used if you need a feeding tube for a longer time, such as during a recovery period from radiation therapy or after a very big operation.

Depending on the way the tube is inserted, it may be done while you’re awake or under anaesthetic. The tube may be inserted by endoscope (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or PEG tube), using an x-ray (radiologically inserted gastrostomy or RIG tube), or surgically (surgical gastrostomy).

Malnutrition and weight loss

Some side effects may make eating difficult, which can cause you to lose weight. Even a small drop in your weight, especially over a short period of time, may put you at risk of malnutrition.

Unplanned weight loss and malnutrition can affect how you respond to treatment, and side effects may be more severe and your recovery slower. You can be malnourished even if you are overweight.

Learn more

Changes to speech

The ability to talk can be affected by surgery and radiation therapy. This may be because of side effects such as swelling and irritation, because of a tracheostomy or laryngectomy, or because other structures have been removed.

You may find it hard to speak clearly or notice that your speech is slurred, or you may find your voice has changed. The extent of any changes will vary depending on the location of the cancer, how advanced it was, and the treatment you had.

How to manage speech changes

- Talking will take time and practice – it’s natural to feel distressed, frustrated and angry at times. You will need to get used to the way your new voice sounds.

- Try non-verbal ways to communicate – gesture, point, nod, smile, mouth words, write things down or ring a bell to call people.

- Use a computer, tablet, mobile phone or notebook to write and send notes.

- Work with a speech pathologist to improve your speech and learn ways to communicate with family and friends. They may give you some exercises to improve the strength and range of motion of the lips, tongue, jaw and larynx.

- Encourage family and friends to be honest if they don’t understand you and to learn new ways to communicate with you. Ask them not to avoid conversation even if it is difficult at first. They may need to be patient and give you time to respond.

- It can be frustrating and difficult when you can't communicate. It may help to have someone you trust to advocate for you or explain what you're trying to say.

- Speak to a counsellor or psychologist if you are finding it difficult to cope with speech changes.

- The National Relay Service can help you make phone calls.

Breathing changes

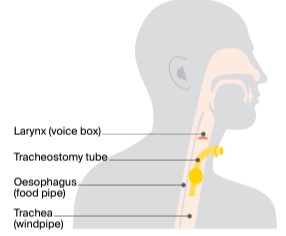

Some people treated for head and neck cancer need a tracheostomy. This is an alternative airway created in the front of the neck so they can keep breathing freely.

Having a tracheostomy

A small cut in the lower neck allows a tube to be inserted into the windpipe. This can be used for breathing during and after surgery when the mouth or throat becomes swollen.

It is usually removed within one week of surgery once the swelling has gone down. In some cases, a tracheostomy is needed for longer or even during radiation therapy, but this is uncommon.

The thought of a tracheostomy may be confronting and scary – talk to your treatment team about how you are feeling and ask them to explain why it is needed. Initially you may not be able to speak, but you will be supported by your treatment team, especially the speech pathologist and physiotherapist.

Once the tracheostomy tube is removed, the hole in your neck normally closes within days. During this time, your voice may be weak and breathy, but will return to normal when the hole closes.

Having a laryngectomy

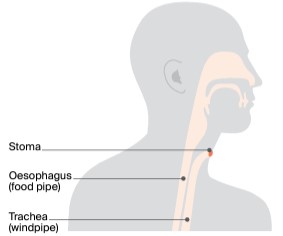

If you have a total laryngectomy, a permanent stoma or breathing hole will be created in your lower neck at the time of the surgery. This will be discussed with you before surgery so you know exactly what to expect, including how you will speak again.

If you need a permanent stoma, the speech pathologist and nurses will teach you how to look after it.

If the larynx (voice box) is removed, there are various ways to speak:

- Voice prosthesis speech – the surgeon makes an opening between your trachea and oesophagus (tracheoesophageal fistula or puncture). A small voice prosthesis (or valve) is inserted to direct air from your trachea to the oesophagus. This will allow you to speak clearly in a low-pitched, throaty voice.

- Mechanical speech – a battery-powered device (electrolarynx) is used to create a mechanical voice. The device is held against the neck or cheek or placed inside the mouth. You press a button on the device to make a vibrating sound.

- Oesophageal speech – you swallow air and force it up through your oesophagus to produce a low-pitched sound. This method can be difficult and you will need training.

Living with a tracheostomy or stoma

Having a tracheostomy or stoma is a big change and takes some getting used to. Your specialist, nurse or speech pathologist can explain ways to manage the following concerns:

- caring for the tube or stoma – you will be shown you how to clean and care for the tracheostomy tube or stoma.

- coping with dry air – the air you breathe will be much drier since it no longer passes through your nose and mouth, which normally moistens and warms the air. This can cause irritation, coughing and extra mucus coming out of the tracheostomy tube or stoma. There are products available that cover the stoma or attach to the tracheostomy tube to provide heat and moisture for the windpipe.

- swimming and bathing – you will need to use a special stoma cover to avoid water getting into the windpipe, even in the shower. If you have a laryngectomy stoma, you may not be able to go swimming.

Pain, numbness and stiffness

Ongoing pain, numbness and restricted movement in the head and neck area may lead to distress, low mood, fatigue or reduced appetite. Speak to your treatment team about ways to manage pain and regain movement.

If you have lymph nodes removed from your neck, you may have some nerve damage that makes your neck feel tight and numb, and your shoulders feel stiff and painful.

Some chemotherapy drugs can cause nerve damage that leads to tingling, pain or numbness in the hands and feet. Nerve damage is often temporary but can be permanent.

Not being able to fully open the mouth or jaw is called trismus,and can affect eating, speaking and oral hygiene.

A speech pathologist or physiotherapist can help improve motion, and can give you medicines to reduce pain.

Other physical changes

Changes to appearance

Many types of surgery for head and neck cancer will cause temporary or permanent changes to the way you look. For example:

- Weight loss – it is common to lose weight during treatment and it can be hard to put it back on.

- Feeding tube – people who need a feeding tube or tracheostomy tube may feel self-conscious.

- Scars – improved surgical methods mean that most people won’t have major scarring. Surgeons will try to hide scars in skin creases in the neck or on the face, and the scars usually fade over time. Scars from radiation therapy may change the colour or texture of the skin.

- Face – in some cases, removing the cancer means removing an eye or part of the jaw, nose, ear or skin. Some people have reconstructive surgery using tissue from another part of the body, while others may have a prosthesis.

- Jaw and teeth – for certain cancers, your surgeon will need to cut through your jaw (mandibulotomy) and reconstruct it with a plate. This involves a cut through your chin and lip, and the scars will be noticeable for some time. If you have lost teeth due to cancer treatment, you may be able to have further surgery to replace or reconstruct them.

- Swelling – surgery or radiation therapy can damage lymph nodes, and this can cause swelling known as lymphoedema.

Give yourself time to get used to any physical changes. Some changes may be temporary and improve with time. Talk about how you are feeling with someone, such as a family member, friend, social worker, occupational therapist or psychologist.

Book into a free Look Good Feel Better workshop and learn how to use skin care, hats and wigs to restore appearance and self-esteem.

Impact on sexuality and intimacy

Head and neck cancer can affect your sexuality in both emotional and physical ways. Reduced interest in sex (low libido) is common and if your appearance has changed, you may worry that you are less sexually attractive or you may be grieving the loss of how you used to look.

Treatment for head and neck cancer sometimes causes side effects such as dry mouth, bad breath, thick and sticky saliva, poor tongue and lip movement, facial palsy, scars, or a stiff neck and jaw. These side effects can all make kissing and oral sex difficult or less pleasant.

Surgery to the mouth may reduce feeling in the tongue or lips. This can affect the enjoyment and stimulation from kissing, but feeling should return in 12–18 months. If your speech is altered, this may affect your self‑esteem and ability to express yourself during sex.

You or your partner may be afraid of having sex if the cancer was HPV-related. Talk to your doctors if you are concerned about the risk of passing on HPV to a long-term or new partner.

Some people choose to express their feelings in other ways, such as cuddling, holding hands or touching cheek-to-cheek. You may wish to talk to a psychologist or sexual health professional, by yourself or with a partner, to help you find ways to adapt to any sexual changes.

Vision changes

If the cancer is in your eye socket, the surgeon may have to remove your eye (orbital exenteration). The empty eye socket will be replaced by a sphere of tissue from another part of your body. This keeps the structure of the eye socket.

Later you can be fitted for an artificial eye, which is painted to look like your remaining eye and surrounding tissue. The eye is like a large contact lens that fits over the new tissue in the eye socket.

You will still be able to see with your remaining eye, but your depth perception and peripheral vision won’t be as good. You will usually still be able to drive and play sport, but it may take time to get used to the changes. Before you start driving again, tell your driver licensing authority about the changes in your vision, as there may be restrictions you have to follow.

Hearing loss

Some treatments for head and neck cancer can affect your hearing. Certain chemotherapy drugs can cause hearing loss. Sometimes the first sign of this is ringing in the ears (tinnitus), so let your doctors know if you experience this.

Radiation therapy can damage the internal structure of the ear, causing fluid to build up behind the eardrums and leading to loss of hearing. Some surgeries to the head and neck, especially for nasopharyngeal cancer, can cause temporary or permanent hearing loss.

Ask your treatment team whether you are at risk of hearing loss and if you should have your hearing tested after treatment ends.

Lymphoedema

If lymph nodes have been removed in a neck dissection or damaged by radiation therapy, it may prevent lymph fluid from draining properly. The fluid can build up and cause swelling in the neck, face and throat. This is known as lymphoedema. It can be temporary or permanent and may change your appearance.

People who have had surgery followed by radiation therapy to the neck are more at risk, especially if both sides of the neck are treated, as well as those who have had a lot of lymph nodes removed. Symptoms of lymphoedema are easier to manage if the condition is treated early.

Sometimes the swelling and other signs of lymphoedema can take months or years to develop, although some people who are at risk never develop the condition.

Life after treatment

After treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread.

You may have blood tests and imaging scans, as well as physical and visual examinations of your head and neck.

You will receive continued support from a speech pathologist, dietitian, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, psychologist and social worker if you need it. You may also be asked to see your dentist regularly.

For some people, head and neck cancer does come back after treatment (recurrence). Sometimes this will be another cancer of the head and neck, but it can also be the original cancer that has spread.

The treatments you are offered will vary depending on your previous treatments and it is important that you are reviewed by an experienced multidisciplinary team.

Question checklist

Asking your doctor questions will help you make an informed choice about your treatment and care. You may want to include some of the questions below in your own list:

Diagnosis

- What type of head and neck cancer do I have?

- Has the cancer spread? What do the staging numbers mean?

- Are the latest tests and treatments for this cancer available in this hospital?

- Will a multidisciplinary team be involved in my care?

- Are there clinical guidelines for this type of cancer?

Treatment

- What treatment do you recommend? What is the aim of the treatment?

- Are there other treatment choices for me? If not, why not?

- I’m thinking of getting a second opinion. Can you recommend anyone?

- How long will treatment take? Will I have to stay in hospital?

- Are there any out-of-pocket expenses not covered by Medicare or my private health cover? Can the cost be reduced if I can’t afford it?

- How will we know if the treatment is working?

- Are there any clinical trials or research studies I could join?

Side effects

- What are the possible side effects of the treatment? Will they be permanent?

- Will I have a lot of pain? What will be done about this?

- Can I work, drive and do my normal activities while having treatment?

- Will the treatment affect my sex life and fertility?

- Are there any complementary therapies that might help me?

- Will my face or neck have significant scarring or will I look different?

- Will I need to have a tracheostomy or stoma? Will my speech be affected?

- How will my eating be affected? Will I need a feeding tube?

- What kind of rehabilitation can I have?

After treatment

- How often will I need check-ups after treatment?

- If the cancer returns, how will I know? What treatments could I have?

Seeking support

A cancer diagnosis can affect every aspect of your life. You will probably experience a range of emotions – fear, sadness, anxiety, anger and frustration are all common reactions. Cancer also often creates practical and financial issues.

There are many sources of support and information to help you, your family and carers navigate all stages of the cancer experience, including:

- information about cancer and its treatment

- access to benefits and programs to ease the financial impact of cancer treatment

- home care services, such as Meals on Wheels, visiting nurses and home help

- aids and appliances

- support groups and programs

- counselling services.

The availability of services may vary depending on where you live, and some services will be free but others might have a cost.

To find good sources of support and information, you can talk to the social worker or nurse at your hospital or treatment centre, or get in touch with Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Understanding Head and Neck Cancers

Download our Understanding Head and Neck Cancers booklet to learn more.

Download now