Page last updated: February 2026

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Head and Neck Cancers - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2026 edition). This webpage was last updated in February 2026.

Expert content reviewers:

This information is based on international and Australian clinical practice guidelines for head and neck cancers.

All updated content has been clinically reviewed by A/Prof Martin Batstone, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon and Director of the Maxillofacial Unit, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD.

This edition is based on the previous edition, which was reviewed by the following panel:

- A/Prof Martin Batstone, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon and Director of the Maxillofacial Unit, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD

- Polly Baldwin, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA

- Martin Boyle, Consumer

- Dr Teresa Brown, Assistant Director Dietetics, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Honorary Associate Professor, University of Queensland, QLD

- Dr Hayley Dixon, Head, Clinical Support Dentistry Department, WSLHD Oral Health Services, Public Health Dentistry Specialist, NSW

- Head and Neck Cancer Care Nursing Team, Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC

- Rhys Hughes, Senior Speech Pathologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Dr Annette Lim, Medical Oncologist and Clinician Researcher – Head and Neck and Non-melanoma Skin Cancer, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Dr Sweet Ping Ng, Radiation Oncologist, Austin Health, VIC

- Deb Pickersgill, Senior Clinical Exercise Physiologist, Queensland Sports Medicine Centre, QLD

- John Spurr, Consumer

- Kate Woodhead, Physiotherapist, St Vincent’s Health, Melbourne, VIC

- A/Prof Sue-Ching Yeoh, Oral Medicine Specialist, University of Sydney, Sydney Oral Medicine, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW.

Head and neck cancers may be treated in different ways, depending on the type, location and stage of the cancer, your general health and what is important to you.

The key treatments for head and neck cancers are:

- surgery

- radiation therapy

- chemotherapy

- immunotherapy

- targeted therapy

You may have one or more treatments, and may be able to have new treatments through clinical trials.

Treatment will be tailored to your situation. Most head and neck cancers and some complex skin cancers of the head and neck should be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT) in a specialised head and neck cancer centre.

Preparing for treatment

It is important to look after your health before treatment begins. This will help you cope with side effects and can improve treatment outcomes.

- Stop smoking – aim to quit before starting treatment. See your doctor or call the Quitline on 13 7848.

- Begin or continue an exercise program – exercise will help build up your strength for recovery.

- Improve your diet and nutrition – a dietitian can suggest ways to get the right nutrition before, during and after treatment, which will help maintain your weight and muscle mass, improve your strength and energy levels, and may mean the treatment works better.

- Avoid alcohol – alcohol irritates mouth sores from the cancer or treatment.

- See a dentist – treatments for head and neck cancer can affect your mouth, gums and teeth. Your specialist may refer you to a dentist or oral medicine specialist who understands the treatments you will be having. You will need a full check-up and an oral health care plan covering any dental work you need and how to care for your mouth.

- Consider the costs – there can be extra costs during cancer treatment. Your health care providers should talk to you about how much you’ll pay for tests, treatments, medicines and hospital care. This is called informed financial consent.

Your guide to best cancer care

A lot can happen in a hurry when you’re diagnosed with cancer. The guide to best cancer care for head and neck cancer can help you make sense of what should happen.

It will help you with what questions to ask your health professionals to make sure you receive the best care at every step.

Read the guide

Surgery

The aim of surgery is to completely remove the cancer and preserve the functions of the head and neck area, such as breathing, swallowing and talking.

The surgeon will cut out the cancer and a margin of healthy tissue, which is checked by a pathologist to make sure all the cancer cells have been removed. Often some lymph nodes will also be removed.

Thinking about having surgery to your head and neck area can be frightening. Talking to your treatment team can help you understand what will happen. You can also ask to see a social worker or psychologist for emotional support before or after the surgery.

Removing lymph nodes

If the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in your neck, or it is highly likely to spread, your surgeon will probably remove some lymph nodes. This operation is called a neck dissection or lymphadenectomy.

Most often lymph nodes are removed from one side of the neck, but sometimes they need to be removed from both sides. A neck dissection may be the only surgery needed, or it may be part of a longer head and neck operation.

The surgeon will make a cut under your jaw and sometimes down the side of your neck. You will often have a small tube (drain) in your neck to remove fluids from the wound for a few days after the surgery.

A neck dissection may affect how your shoulder moves and your neck looks after surgery. A physiotherapist can help improve movement and function.

How the surgery is done

Different surgical methods may be used to remove the cancer. Your doctor will advise which method is most suitable for you. The options may include:

- endoscopic surgery – a rigid instrument with a light and camera is inserted through the nose or mouth to see and remove some cancers, particularly from the nose and sinuses.

- transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) – a microscope (usually with a laser attached) is used through the mouth to remove cancers, particularly of the larynx and lower throat.

- transoral robotic surgery (TORS) – the surgeon uses a 3D telescope and instruments attached to robotic arms to reach the cancer through the mouth. It is often used for oropharyngeal cancers.

- open surgery – the surgeon makes cuts in the skin of the head and neck to remove cancers. It is used for larger cancers and those in difficult positions. Part of the upper and lower jaw or skull may need to be removed and then replaced or reconstructed.

Minimally invasive surgery such as endoscopic, TLM and TORS usually means less scarring, a shorter hospital stay and faster recovery. However, these types of surgery are not possible in all cases, and open surgery is often the best option.

Reconstructive surgery

After open surgery, you may need reconstructive surgery to rebuild your tongue, mouth or jaw and help with speech and swallowing, and to improve how the area looks. It is usually part of the operation to remove the cancer, but is sometimes done later.

In reconstructive surgery, a combination of skin, muscle and sometimes bone is used to rebuild the area. This can be taken from another part of the body and is called either a “free flap” or a “regional flap”.

Occasionally synthetic materials such as silicone and titanium are used to re-create bony areas or other structures in the head and neck, such as the palate. This is called a prosthetic.

Surgery for oral cancer

The type of surgery depends on the cancer’s size and location. Localised cancers can be treated by removing part of the tongue, mouth or lip.

For larger cancers, the surgery will affect a bigger area and you may need reconstructive surgery so you can continue to chew, swallow or speak.

Some tumours can be removed through the mouth, but you may need open surgery for larger tumours. Different types of oral surgery include:

- glossectomy – removes part or all of the tongue

- mandibulectomy – removes part or all of the lower jaw (mandible)

- maxillectomy – removes part or all of the upper jaw (maxilla).

Surgery for pharyngeal cancer

Pharyngeal cancers are treated differently depending on which part of the pharynx is affected.

Surgery is used for many oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Nasopharyngeal cancers are usually treated with chemotherapy, radiation therapy or chemoradiation, and rarely treated with surgery.

Small oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers can often be treated with minimally invasive surgery, sometimes followed by radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

If the cancer is large or advanced and surgery is an option, it is more likely to be open surgery through a cut in the neck.

Surgery is often followed with radiation therapy and possibly chemotherapy. If surgery is not possible due to the size or location of the tumour, radiation therapy or chemoradiation is usually given instead.

Different types of pharyngeal surgery include:

- hypopharyngectomy – removes part of the hypopharynx (lower throat)

- pharyngolaryngectomy – removes all of the larynx and part of the pharynx; this surgery is less common and is similar to a total laryngectomy

- oropharyngectomy – a less common surgery that removes some of the oropharynx (the part of the throat behind the mouth).

Surgery for laryngeal cancer

If laryngeal cancer is at an early stage, you may have surgery to remove part of the larynx (partial laryngectomy).

The surgery may be minimally invasive or open. It often takes up to six months for the voice to recover. In some cases, the changes to the voice may be permanent.

If the cancer has advanced and chemoradiation isn't an option, you may need open surgery to remove the larynx (total laryngectomy). This operation removes the whole larynx and separates the windpipe (trachea) from the food pipe (oesophagus).

After this surgery, you will permanently breathe through a hole in the front of your neck called a laryngectomy stoma.

Because this surgery removes the voice box, you won’t be able to speak in the same way. A speech pathologist will teach you new ways to talk and communicate.

If you have a total laryngectomy, part or all of your thyroid gland may be removed (thyroidectomy).

The thyroid produces thyroxine (T4), the hormone that controls your metabolism, energy levels and weight, so you may need to take thyroid hormone replacement tablets every day for the rest of your life. Talk to your doctor for more details.

Surgery for nasal or paranasal sinus cancer

Your doctor may advise you to have surgery if the tumour isn’t too close to your brain or major blood vessels.

The type of surgery will depend on where the tumour is and, if you have paranasal sinus cancer, which sinuses are affected. You will often need to have reconstructive surgery as well.

Nasal and sinus cancers are often close to the eye socket, brain, cheekbones and nose. Your surgeon will talk to you about the most suitable approach and whether any other parts of the head or neck may need to be removed to get the best outcome.

Different types of surgery for nasal and sinus cancer include:

- maxillectomy – removes part or all of the upper jaw (maxilla), which may include the upper teeth, part of the eye socket and/or the nasal cavity.

- skull base surgery – also known as a craniofacial resection, this surgery removes part of the nasal cavity or sinuses. It is often done endoscopically through the nose, but a cut along the side of the nose may be needed.

- orbital exenteration – removes the eye and may also remove tissue around the eye socket.

- rhinectomy – removes part or all of the nose.

The surgeon will consider how the operation will affect how you look, and your ability to breathe, speak, chew and swallow.

If your nose, or a part of it, is removed, you may get an artificial nose (prosthesis) or the nose may be reconstructed using tissue from other parts of your body.

Surgery for salivary gland cancer

Most salivary gland tumours affect one of the parotid glands, which sit in front of the ears. Surgery to remove part or all of a parotid gland is called a parotidectomy.

The facial nerve runs through the parotid gland. This nerve controls facial expressions and movement of the eyelid and lip.

If it is damaged during surgery, you may be unable to smile, frown or close your eyes. This is known as facial palsy, and it will usually improve over several months.

In some cases, the facial nerve needs to be cut so the cancer can be removed. This will affect how your face looks and moves. There are various procedures that can help improve this, such as using a nerve from another part of the body (nerve graft).

If the cancer affects a gland under the lower jaw (submandibular gland) or under the tongue (sublingual gland), the gland will be removed, along with some surrounding tissue.

Nerves controlling the tongue and lower part of the face may be damaged, causing some loss of function.

What to expect after surgery

How you feel after surgery will vary greatly depending on your age, general health, how large an area is affected and whether you also have reconstructive surgery.

Your surgeon can give you a better idea of what to expect after the operation.

Staying in hospital

How long you stay in hospital depends on the type of surgery you have, the area affected, and how well you recover.

Surgery to remove some small cancers can often be done as a day procedure. Recovery is usually fast and there are often few long-term side effects.

Surgery for more advanced cancers often affects a larger area, can involve reconstructive surgery and may last all day.

You may need care in the intensive care unit before being transferred to the ward, and side effects may be long term or permanent.

Once you return home, you may be able to have nurses visit to provide follow-up care.

Side effects

Most surgeries for head and neck cancer will have some short-term side effects, such as discomfort and a sore throat. Recovery after a larger surgery may be more challenging, especially at first.

Depending on the type of surgery you’ve had, after a period of recovery, you may not have any ongoing issues. However, some people do need to adjust to permanent changes after head and neck surgery.

Long-term side effects can include:

- reduced energy levels

- difficulty eating (e.g. chewing or problems with teeth)

- speech changes

- breathing changes

- change in appearance

- changes to intimacy and your sex life

- vision and hearing changes

- pain, numbness, swelling (lymphoedema) or less movement in the area.

Ask your treatment team about what side effects you can expect. Tell them if you experience any side effects that worry you or are ongoing.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. For head and neck cancer, it is most often given with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT).

A technique called intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) targets the radiation precisely to the cancer, which reduces treatment time and causes as little harm as possible to nearby healthy tissue.

- As the main treatment – for some pharyngeal and laryngeal cancers, radiation therapy will be the main treatment, with the aim of destroying the cancer while maintaining normal speech, swallowing and breathing. Sometimes chemotherapy will also be used to make the radiation work better (chemoradiation). Radiation treatment usually is given daily for 7 weeks for most head and neck cancers, but this may vary from person to person.

- After surgery – radiation therapy is often used after surgery for head and neck cancers (adjuvant treatment). The aim is to destroy any remaining cancer cells and reduce the chance of the cancer coming back. You will probably start radiation therapy as soon as your wounds have healed and you’ve recovered your strength, which should be within 6 weeks. Adjuvant radiation therapy is sometimes given together with chemotherapy (chemoradiation). This is usually given for about 6–7 weeks, but may vary person to person.

Before radiation therapy, you meet with a radiation oncologist to work out whether radiation therapy is right for you. You will have a planning session with a CT scan to show the exact area that needs the radiation.

External beam radiation therapy

Having radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is carefully planned to make sure enough radiation reaches the cancer, while as little as possible reaches healthy organs and tissues.

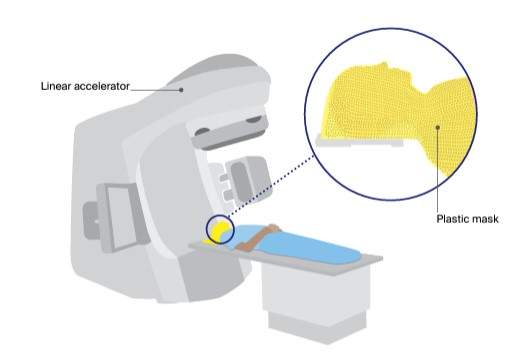

During treatment sessions, you will lie on a table under a machine called a linear accelerator, which precisely delivers the radiation.

The treatment is painless and is usually given Monday to Friday for 6–7 weeks. You usually won’t need to stay in hospital.

Wearing the mask

You wear the plastic mask for about 10–20 minutes at each session. It helps you keep still and makes sure the radiation is targeted at the same area at each treatment session.

You can see and breathe easily, but it may feel strange and confined at first. Tell the radiation therapists if you have claustrophobia or the mask makes you feel uncomfortable – you can talk to someone or may be offered medicine to help you relax.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation therapy side effects vary depending on the area treated, the number of sessions, and whether it is combined with chemotherapy. Side effects often get worse 1–3 weeks after treatment ends and then start to improve.

Some side effects may last longer, be ongoing or appear several months or years later. Some may be permanent. It is important to talk to your treatment team if you have any concerns or questions on how the treatment may affect you.

The most common short-term and long-term side effects are listed below.

- During or immediately after treatment – Short-term side effects can include fatigue, mouth sores, taste changes, nausea, loss of appetite, mouth infection (oral thrush), dry mouth, thick saliva and phlegm, swallowing difficulties, skin redness, burning and pain in the area treated, breathing difficulties and weight loss.

- Ongoing – Longer-term or permanent side effects may include dry mouth, thick saliva, difficulties with swallowing and speech, changes in taste, fatigue, muscle stiffness, neck swelling, appetite and weight loss, mouth infection (oral thrush), hoarseness, dental problems such as tooth decay and gum disease, difficulty opening the mouth, and hair loss.

- Aspiration – Some people develop a temporary or ongoing problem where fluid or food enters the windpipe (trachea) while swallowing. This is called aspiration and it can cause coughing, lung infections such as pneumonia and, sometimes, difficulty breathing).

- Thyroid damage – If the treatment damages the thyroid, it can cause an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism). This can be managed with thyroid hormone replacement tablets.

- Osteoradionecrosis of the jaw – Radiation therapy can damage blood vessels, reducing the blood supply to the area treated. Occasionally, the bone starts to die, leading to pain, infection and fractures. This is known as osteoradionecrosis, or ORN. About 5–7% of people who have radiation therapy to the head and neck develop ORN of the jaw. It can occur months or years later, most commonly after having dental work such as the removal of teeth, when the bone is unable to heal itself. This is why you will usually see a dentist before your cancer treatment, so any dental issues can be treated before there is a risk of ORN.

It is very important to tell your dentist that you have had radiation therapy before beginning any dental work. Treatment for ORN may include antibiotics, other medicines or surgery.

To help the bone heal, some people may also have hyperbaric oxygen treatment (breathing in concentrated oxygen in a pressurised chamber).

"I had never seen a mask like this and I had never heard about its purpose. A combination of listening to music, light sedation and support from a psychologist helped a great deal." JULIE

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells.

You will usually receive chemotherapy by injection into a vein (intravenously), although it is occasionally given as tablets. How often you have chemotherapy sessions will depend on the treatment plan.

Chemotherapy may be given for a range of reasons:

- in combination with radiation therapy (chemoradiation), to increase the effects of radiation

- before surgery or radiation therapy (neoadjuvant chemotherapy), to shrink a tumour

- after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy), along with radiation therapy, to reduce the risk of the cancer returning

- as palliative treatment to relieve symptoms such as pain.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can affect the healthy cells in the body and cause side effects. Everyone reacts differently to chemotherapy, and effects will vary according to the drugs you are given. Some people may have few side effects, while others have many.

Not all chemotherapy causes nausea. Your medical oncologist or nurse will discuss likely side effects, including how these can be prevented or controlled with medicine.

Common side effects can include tiredness and fatigue; nausea and/ or vomiting; tingling or numbness in fingers and/or toes (peripheral neuropathy); changes in appetite and loss of taste; diarrhoea or constipation; hair loss; low red blood cell count (anaemia); hearing loss; ringing in the ears (tinnitus); lower levels of white blood cells, which may increase the risk of infection; and mouth sores.

Keep a record of the names and doses of your chemotherapy drugs handy. This will save time if you become ill and need to go to the hospital emergency department.

Other drug therapies

Some head and neck cancers – most commonly those that have come back – may be treated with other drug therapies that reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic therapies).

These may include targeted therapy and immunotherapy, which work in different ways to chemotherapy. They can be combined with other treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy targets specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. Tests may be done on a biopsy sample to look for these specific features.

Each targeted therapy drug works on a particular feature, and the drug will only be given if the cancer cells have that feature.

For some head and neck cancers, targeted therapy drugs are occasionally used when people cannot take the standard chemotherapy drug or the cancer is advanced.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. The main type of immunotherapy drugs used in Australia are called checkpoint inhibitors. They help the immune system to recognise and attack cancer cells.

Checkpoint inhibitors may be used to treat some types of advanced head and neck cancer.

New targeted therapy and immunotherapy drugs are often studied in clinical trials. Ask your doctor if this is an option for you.

Learn more

Palliative treatment

In some cases of very advanced head and neck cancer, the medical team may talk to you about palliative treatment. This aims to improve your quality of life by managing the symptoms without trying to cure the disease.

When used as palliative treatment, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or other drug therapies can help manage pain and other symptoms, and may also slow the spread of the cancer.

Head and neck cancer clinical trials

Cancer clinical trials are research studies that test whether a new approach to prevention, screening, diagnosis, or treatment works better than current methods and is safe.

There are clinical trials for head and neck cancers open to recruitment in Victoria. This list shows the most recently updated head and neck cancer studies on the Victorian Cancer Trials Link (VCTL).

Visit the VCTL to find more head and neck cancer clinical trials.