Our children, teens and young adults information is currently under review. For cancer information and support, please contact our cancer nurses on 13 11 20. For information relating to paediatric cancer types, treatment and care, see The Royal Children’s Hospital and the Paediatric Integrated Cancer Services (PICS) websites, or speak with your doctor.

Day to day life for a child with cancer can be very difficult both for the child and those caring for them. Parents and the patient can face many challenges and changes. At times parents may feel overwhelmed and unsure about what the future holds. Knowing what to expect and who to get support from can help the family cope throughout treatment.

Nutrition and diet

The physical and emotional side effects of having cancer and its treatment can cause several changes to a child’s ability and desire to eat. Physical side effects that can alter a child’s eating patterns may include:

- Loss of appetite

- Feeling or being sick (nausea and vomiting)

- Bowel changes (diarrhoea or constipation)

- Weight gain

- Sore mouth

- Altered sense of taste

- Feeling tired all the time and not having the energy to eat

How cancer and its treatment affect a child emotionally may also affect their eating habits. Some children who are upset, frightened or anxious will not want to, or feel able to eat.

The medical team, including the dietitian, will work closely with the child and family to ensure maintenance of a good level of nutrition during their treatment.

For more information regarding eating well, please refer to:

Fatigue (tiredness)

Fatigue is one of the most common side effects of cancer treatment. It can be acute (short lasting) or chronic (long lasting).

It can be difficult to understand how tired someone having cancer treatment sometimes feels. Whilst a child may not seem to be doing much to make them tired, their body is working hard to fight the cancer and manage the effects of the treatment. Children can become exhausted and have no energy. Fatigue can sometimes carry on long after treatment has finished. Plan appropriate rest periods during the low energy times.

Children having radiotherapy to the brain usually want to sleep a lot. Doctors call this somnolence.

The following may help to manage fatigue and sleepiness:

- Minimise the number of visitors at any one time (visitors are great but too many can be exhausting too!).

- Offer food and drink regularly to keep up energy levels.

- Allow periods of rest.

- Encourage low energy activities such as reading, watching TV.

- Help with activities of daily living (bathing, dressing, and eating) during very low energy times.

- Avoid outings that require walking long distances/crowds and busy places.

- Create a calm, comfortable and reassuring environment both at home and in hospital.

For more information about fatigue you can read the following:

Blood counts

Children with cancer usually need to have regular blood tests. This is to check their blood counts (red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets) are staying within normal limits during their treatment. There are three main types of blood cells:

- Red blood cells - These carry oxygen around the body. If they become too low, known as anaemia, a child can become breathless, very tired and generally unwell.

- White blood cells - These cells help fight infection in the body. If they become too low, known as neutropaenia, a child will be more susceptible to getting infections. This can be very dangerous when a child is having cancer treatment.

- Platelets - These cells are important for blood clotting. If they get too low it can cause serious problems with bleeding.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy can cause changes to all these blood cells which may lead to infections, bleeding and tiredness. Understanding blood counts, and how to prevent complications if they become low, is an important part of caring for a child.

Hair loss

Nearly all children diagnosed with cancer lose their hair at some stage from treatment. The amount of hair loss will depend on the type of treatment. Hair loss generally begins two to three weeks after chemotherapy starts. The hair may all come out overnight, or take several weeks. It can range from severe thinning to complete baldness and can include body hair, eyebrows and eyelashes. Hair will always grow back but it may look different.

It can be distressing and upsetting to lose hair. Using hair wraps, bandanas and hats can help a child until their hair grows back. Cancer Council Victoria offers a free wig service that some teenage children may want to use.

Mouth and dental care

Some chemotherapy drugs can cause mouth sores such as ulcers or infections. Radiotherapy to the head and neck area can also cause mouth problems. The child’s doctor should be notified of changes in the mouth or throat such as:

- sores

- ulcers or changes in saliva or problems with eating and swallowing

- red or white patches in the mouth

- coated white tongue or

- bleeding gums

Dental problems should be discussed with a child’s doctor before seeing the dentist. If a child needs any dental work, the dentist needs to be notified that the child is having cancer treatment.

School issues

It is important for both the patient and parents to maintain contact with the child’s school, teachers and school friends whilst having cancer treatment. Continuing to engage a child during treatment in learning may be challenging at times, but it is also an important part of recovery. Writing a letter or meeting with the Principal or key teachers at the school early on in a child’s illness helps open the lines of communication. Visiting programs may be available to help educate and inform the child’s school friends and teachers.

Stay in close contact with the child’s teachers, use the teachers within the hospital setting and ask the child’s friends to visit and do school work with them. All of this can help keep the child active in their education. Providing regular updates about a child’s progress and possible return to school will be an advantage for everyone.

Depending on the child’s age there maybe difficulties upon returning to school. Issues such as hair loss, weight loss, weight gain, speech problems, changes in appearance due to surgery, loss of concentration and the ability to learn as well as they could before may all be experienced. Fatigue can be an ongoing issue for many cancer patients long after their treatment finishes.

For more information regarding how schools and parents can support children receiving treatment for cancer please:

Physical activity

Children may not feel like playing, exercising or being active during cancer treatment. This is normal and usually for a good reason. Having cancer and its treatment is exhausting for most people, including children. They may be feeling sick, have a fever or low blood cell count.

Whilst it is important to allow children to rest where possible, it is also important to know when to encourage exercise. Prolonged inactivity can lead to feeling more tired and can lead to other problems such as muscle weakness and low mood.

Where possible, and when appropriate, encourage activity. Involvement in the daily routines of family activity such as cutting up vegetables for dinner, folding washing and playing games can help. Walking, bike rides and light exercise can have a positive effect during their treatment. Avoid strenuous exercise and always check with the child’s doctor before doing any new exercise program. There may be days when all a child wants to do is sleep, other days they will be happy to be quite active.

Pain

Children undergoing treatment may have some pain because of the treatment or the cancer itself.

Why does cancer cause pain?

Pain happens when nerves detect damage to the body and send a message to the brain, causing the sensation of pain to occur. Pain is useful when it helps you avoid doing something risky, like putting your hand in very hot water. With cancer and other illnesses, it can alert you to the fact that there is a problem, like a tumour growing. Pain can also be experienced due to the effects of treatment. Pain in cancer can happen for different reasons:

- a tumour can press on a nerve or affect the way an organ works

- chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy can cause pain

- nerves can ‘carry' pain around the body, so pain can sometimes be felt in a place well away from the thing that is causing it. This is called ‘referred' pain.

How does a child know how to describe how their pain feels?

For very small children watching their facial expressions, movements and the way they cry can indicate levels of pain. Older children will usually be able to tell you about their pain. It is important to find out where the pain is, the type of pain (burning, shooting, cramping, throbbing, stabbing, dull, sharp, constant, aching.) and what makes it worse (movement, eating, breathing) or better (changing position, resting, pain killing medications). Changes in behaviour, such as isolation, mood changes and loss of appetite can indicate a child is in pain.

For older children, asking them to rate their pain on a scale of 1 to 10 can be helpful. If their pain is mild - similar to a minor headache that you know will go away soon - they might rate it 1 or 2. The other end of the scale, 9 or 10, is very severe pain – and could be the worst thing they could experience. Always tell the child’s doctor if pain changes suddenly or becomes more severe.

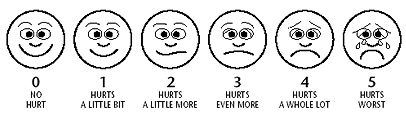

Small children may benefit from using drawings with facial expressions to communicate their level of pain. Some children may be afraid to talk about their pain or not know what words to use. Speak at an age-appropriate level to the child to find out about their pain. For example, ‘is it just a little ouch like when you knock your hand on the table or is it a big ouch like when you fall down and cut your knee or much worse than that?”. Children will find it easier to tell you about their pain if you give examples.

Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, which can be used with children as young as 3 years old is also used with some children. It works in a similar way to using a number scale for the older child to rate their pain. Each face has an expression on it and a number associated with that expression. The faces are numbered 0 to 5 with 0 meaning no pain at all and 5 being the worst pain of all.

From Wong, D.L., Hockenberry-Eaton, M., Wilson, D., Winkelstein, M.L., Ahmann, E., DiVito-Thomas, P.A.: Whaley and Wong's Nursing Care of Infants and Children, ed. 6, St. Louis, 1999, p. 2040. Copyrighted by Mosby, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

For more information about cancer pain and its treatment:

Please note that the information on these international websites is about pain and cancer in general and not specific to children.

Caring for a child with cancer

Caring for someone with cancer can be very stressful, particularly when it is a child. The child with cancer may be experiencing distressing emotions about their cancer diagnosis, side effects from treatment and mood changes from the effects of medications. It is very important that carers of children with cancer look after themselves during this time. Having time out, a cup of coffee with a friend, and sharing worries and concerns with someone not involved in the child’s care are useful strategies.

Cancer Support Groups are usually open to patients and carers. Support groups can offer the chance to share experiences and ways of coping. There are a range of support services for children with cancer and their carers such as home help and visiting nurses. These are provided by local councils and the Royal District Nursing Service.

Call Cancer Council on 13 11 20 to:

- be linked with another parent by telephone.

- be sent a carer’s kit so that you can find out about financial assistance and other resources.

Play time for the child with cancer

Children love to play and it is often when they are at their happiest. Play remains very important for a child with cancer and should be encouraged throughout treatment. The following websites provide helpful ideas about play.

- The Starlight Foundation has set up an online community designed for young people and their families living with a serious illness such as cancer. LiveWire.org.au

- The Royal Children’s Hospital has developed a list of educational apps and websites a patient can play whilst in hospital. It is arranged by age groups.

Practical and financial issues (finance, child care, travel, insurance)

Many children’s cancer organisations also offer practical assistance.

Including:

- Financial assistance: may be available for transport costs to medical appointments, prescription medicines, or through benefits or pensions – social workers can offer assistance

- Home nursing care: available through district nursing, or the local palliative care service – usually the doctor or hospital arranges this.

- Home care services: aids and appliances: contact the hospital social worker, occupational therapist or local council.

After treatment finishes

When treatment finishes, a range of emotions including relief, excitement, and apprehension can be experienced. Whilst it is a time of celebration, some people are surprised to find that they can be feeling a bit fearful too. Fearful about what the future holds, if the cancer will come back and of returning to everyday life without continuous hospital contact. This is all normal, it is important to get the help when treatment has finished.

Parents and carers may have some of the following questions after treatment finishes:

- Frequency of check ups

- What to do if a child develops a fever

- Cancer and the impact of children learning

- When to return to school

- Who to contact for questions and concerns

- When to get immunisations

- Coping with fear of the cancer coming back

- Travel insurance for the recovering child

For further information:

- The Coming off treatment handbook has been developed by the Paediatric Integrated Cancer Service (PICS) to support families when their child completes treatment.

Late effects of childhood cancer treatment

Major advances in treatment over the past two decades have improved survivorship and because more children are surviving, doctors now know that some cancer treatments can cause problems later in life - have ‘late effects’ - on the person’s health and well being. Watching out for these problems with long-term follow up care ensures that, if problems do arise, they are dealt with early.

Childhood cancer survivors are at risk of developing several possible late effects from their cancer treatment. This does not mean all children who have had cancer treatment will develop late effects. The risk will depend on several factors such as:

- the type of cancer the child had

- which treatments were given and the doses

- the age when receiving the treatments

The following are examples of the main types of problems that can happen later in life after childhood cancer treatment. The child’s doctor is the best person to ask about the possible late effects specific to the child being treated.

Heart or lung problems

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy can cause problems later in life with the heart and lungs, regular heart scans and tests are required.

Growth and development problems

Radiotherapy treatment can cause problems with bone growth.

Learning difficulties

Most children will not have long-term problems with learning after their cancer treatment. However, some children, especially those who have had treatment for a brain tumour, may have learning difficulties. They may need special attention at school to help them keep up with their studies.

Sexual development and fertility issues

Some treatments will affect a child’s sexual organs and functioning in both girls and boys. This can lead to having an effect on sexual development and ability to have children (their fertility). Treatments that may have this effect include:

- radiotherapy to the brain, lower abdomen/pelvic area

- certain chemotherapy drugs

- total body irradiation

- surgery on the ovaries, womb or testes

Developing a second cancer

For a very small number of children who have a childhood cancer there is the risk they will develop another different type of cancer (second cancer) later in life. Having regular appointments with a local general practitioner throughout life is essential for all survivors of childhood cancer.

Expert content reviewers:

Cancer Council Victoria with assistance from The Paediatric Integrated Cancer Service (PICS), parents and staff from the Oncology units at both The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne & Monash Children's, Monash Health, Melbourne and OnTrac, Peter Mac Victorian Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Service.