Page last updated: December 2025

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Testicular Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2025 edition). This webpage was last updated in December 2025.

Expert content reviewers:

This information was developed with help from a range of health professionals and people affected by thyroid cancer:

- A/Prof Peter Grimison, Medical Oncologist, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, NSW

- Marc Diocera, Genitourinary Nurse Consultant, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- A/Prof Peter Heathcote, Urologist, Brisbane Urology Clinic, QLD

- Dr Michael Huo, Radiation Oncologist, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD

- A/Prof Joseph McKendrick, Medical Oncologist, Epworth Eastern Hospital, VIC

- Dr Tonia Mezzini, Sexual Health Physician, East Obstetrics and Gynaecology, SA

- Dominic Oen, Clinical Psychologist, Bankstown Cancer Centre, NSW

- Dr Benjamin Thomas, Urological Surgeon, The Royal Melbourne Hospital and The University of Melbourne, VIC

- Paul Zawa, Consumer

What is testicular cancer?

Cancer that starts in the cells of a testicle is called testicular cancer or cancer of the testis (which means one testicle). Usually, it affects only one testicle, but sometimes both are affected.

As testicular cancer grows, it can spread to lymph nodes in the abdomen (belly) or to other parts of the body, such as other lymph nodes, lungs or liver. It does not spread to the other testicle.

About the testicles

The testicles (also called testes) are part of the male reproductive system, which also includes the penis and prostate. They are two small egg-shaped glands that sit in the scrotum.

The testicles make and store sperm. They also make the hormone testosterone, which is responsible for the development of male characteristics, such as facial hair, a deeper voice and sex drive (libido).

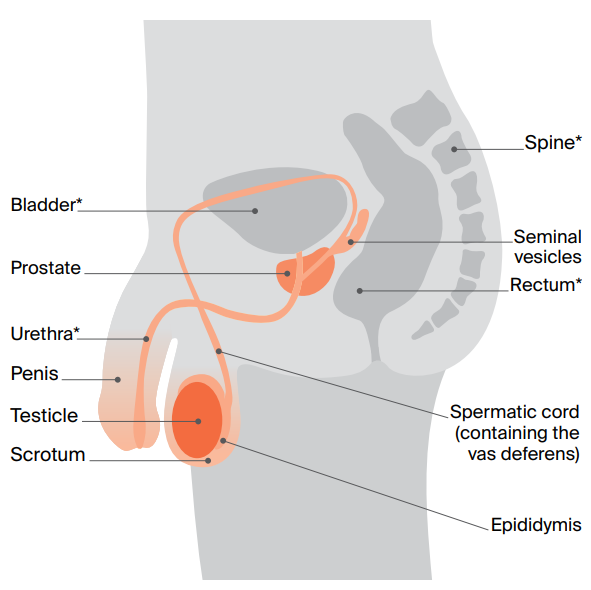

The male reproductive system

- Epididymis – a tube behind each testicle that stores immature sperm

- Spermatic cord – contains blood vessels, nerves, lymph vessels and the vas deferens

- Vas deferens – a long tube that carries mature sperm to the urethra to prepare for ejaculation

- Scrotum – a pouch of skin that holds the testicles

- Seminal vesicles – glands that produce fluid that carries sperm

- Prostate – a gland that produces fluid that helps nourish and protect sperm

- Urethra (not part of the reproductive system) – a tube that runs from the bladder and through the prostate to take urine (pee) out of the body

How common is testicular cancer?

Testicular cancer is not common overall, but it is the most common cancer diagnosed in men aged 20–39 (apart from skin cancers).

About 1026 people in Australia are diagnosed with testicular cancer each year, which is about 1% of all cancers in men.

Anyone with a testicle can get testicular cancer, including men, transgender women, non-binary people and people with intersex variations.

See LGBTQI+ people and cancer for more information.

Learn more about cancer statistics and trends

Types of testicular cancer

The most common testicular cancers are called germ cell tumours. There are two main types:

- Seminoma tumours – tend to develop more slowly than non-seminoma tumours. They usually occur between the ages of 25 and 45, but can occur at older ages.

- Non-seminoma tumours – tend to develop more quickly than seminoma cancers and are more common in late teens and early 20s. There are four main subtypes: teratoma, choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumour and embryonal carcinoma.

A testicular tumour can also include a mix of seminoma and non-seminoma cells, or a combination of the different types of non-seminoma cells. This is called a mixed germ cell tumour and is treated the same as non-seminoma cancer.

A small number of testicular tumours start in cells that make up the supportive (structural) and hormone producing tissue of the testicles. These are called stromal tumours.

The two main types are Sertoli cell tumours and Leydig cell tumours. They are usually benign (not cancer) and are removed by surgery.

What is GCNIS?

Most testicular cancers begin as a condition called germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS). In GCNIS, the cells are abnormal, but they haven’t spread outside the area where the sperm cells develop.

GCNIS is not cancer, but it may develop into cancer. GCNIS has similar risk factors to testicular cancer and is hard to diagnose because there are no symptoms. It can only be diagnosed by testing a tissue sample.

Some GCNIS cases will be carefully monitored (this is called active surveillance), while other cases will be treated with radiation therapy or surgery to remove the testicle.

Risk factors

The causes of testicular cancer are largely unknown, but certain factors may increase your risk of developing it.

Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about any of the following risk factors:

- having germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS)

- diagnosed with testicular cancer previously – if you previously had cancer in one testicle, you are slightly more at risk of developing cancer in the other

- undescended testicles – having undescended testicles at birth increases the risk

- family history – if your father or brother has had testicular cancer, you are slightly more at risk (2%) of developing testicular cancer

- infertility

- HIV or AIDS

- hypospadias – a condition when the opening of the urethra is on the underside of the penis. People born with this condition have a slightly higher risk of developing testicular cancer

- intersex variations – some types of intersex variations, such as partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, can increase the risk of developing testicular cancer.

Symptoms

In some people, testicular cancer does not cause any noticeable symptoms, and it may be found during tests for other conditions. When there are symptoms, the most common ones are:

- a lump or swelling in the testicle (often painless)

- a change in the size or shape of the testicle.

Less common symptoms include a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum or unevenness between the testicles; a pain or ache in the lower abdomen, testicle or scrotum; swollen or tender breast tissue; back pain; or stomach-aches.

Not everyone with these symptoms has testicular cancer. However, it is important to have any lump in your testicles or any ongoing symptoms checked by your doctor.

Understanding Testicular Cancer

Download our Understanding Testicular Cancer booklet to learn more.

Download now