You will usually begin by seeing your doctor, who will examine your testicles and scrotum for a lump or swelling. Some people may find this embarrassing, but doctors are used to doing these examinations. It will only take a few minutes.

If the doctor feels a lump that might be cancer, you will have an ultrasound. If the lump looks like a tumour on the ultrasound, you will have a blood test and are likely to be referred to a specialist called a urologist. The urologist may recommend removal of the testicle to confirm the diagnosis.

Ultrasound

An ultrasound is a painless scan that uses soundwaves to create a picture of your body. This is a very accurate way to tell the difference between fluid-filled cysts and solid tumours. It can show if a tumour is present and how large it is.

The person performing the ultrasound will spread a gel over your scrotum and then move a small device called a transducer over the area. This sends out soundwaves that echo when they meet something dense, like an organ or a tumour. A computer creates a picture from these echoes. The scan takes about five to ten minutes.

Blood tests

Blood tests can check your general health and how well your kidneys and other organs are working. The results of these tests will also help you and your doctors make decisions about your treatment.

Tumour markers

Some blood tests look for proteins produced by cancer cells. These proteins are called tumour markers. If your blood test results show an increase in the levels of certain tumour markers, you may have testicular cancer.

Raised levels of tumour markers are more common in mixed tumours and non-seminoma cancers. It is possible to have raised tumour markers due to other factors, such as liver disease or blood disease. Some people with testicular cancer don’t have raised tumour marker levels in their blood.

There are three common tumour markers measured in tests for testicular cancer:

- alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) – raised in some non-seminoma cancers

- beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) – raised in some non-seminoma and seminoma cancers

- lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) – raised in some non-seminoma and seminoma cancers.

Doctors will use your tumour marker levels to assess the risk of the cancer coming back after surgery, and this helps them plan your treatment. If the diagnosis of testicular cancer is confirmed after surgery, you will have regular blood tests to monitor tumour marker levels throughout treatment and as part of follow-up appointments.

Tumour marker levels will drop if your treatment is successful, but they will rise if the cancer is active. If this happens, you may need more treatment.

Surgery to remove the testicle

The only way to be sure of the diagnosis is to surgically remove the affected testicle and examine it in a laboratory. The surgery to remove a testicle is called an orchidectomy or orchiectomy. In most cases, the surgeon needs to remove only one testicle.

For other types of cancer, a doctor can usually make a diagnosis by removing and examining some tissue from the tumour, which is called a biopsy. Doctors don’t usually biopsy the testicle because there is a small risk that making a cut through the scrotum can cause cancer cells to spread.

A specialist called a pathologist looks at the removed testicle under a microscope. If cancer cells are found, the pathologist can tell which type of testicular cancer it is and provide more information about the cancer, such as whether and how far it has spread (the stage). This helps doctors plan further treatment.

It is rare for both testicles to be affected by cancer at the same time. If they are both removed, you will no longer produce testosterone and will probably be prescribed testosterone replacement therapy.

'Before having one of my testicles removed, I went to the sperm bank as a safeguard. But after 2 years, I was able to father a child normally.’ DJ

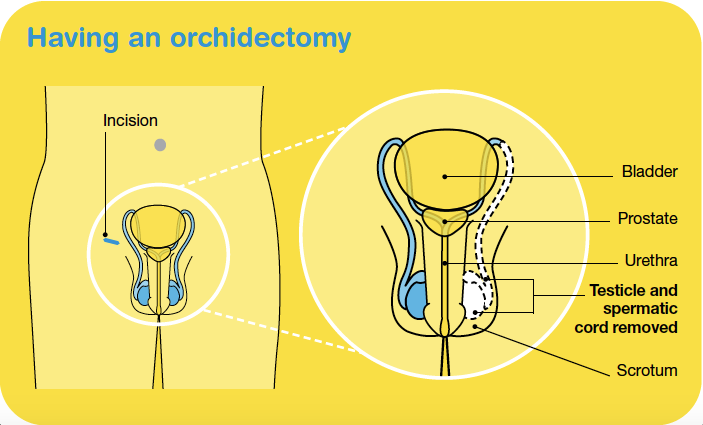

Having an orchidectomy

You will be given a general anaesthetic, then the urologist will make a cut (incision) in the groin above the pubic bone. The whole testicle is pulled up and out of the scrotum through this cut, as well as the spermatic cord because it contains blood and lymph vessels that may act as a pathway for the cancer to spread to other areas of the body. The scrotum is not removed but will no longer contain a testicle.

The operation takes about 60 minutes. After the orchidectomy, you can usually go home the same day, but you may need to stay in hospital overnight.

What to expect after surgery

After an orchidectomy, you will have some pain and discomfort for several days and need to take care while you recover. You will have a few stitches to close the incision, which will usually dissolve after several weeks. There may be some bruising around the wound and scrotum. The scrotum can become swollen if blood collects inside it (intrascrotal haematoma). Both the bruising and the haematoma will disappear over time.

For the first couple of weeks, it’s best to wear underwear that provides cupping support for the scrotum, which is available at most pharmacies. You’ll probably be advised to avoid strenuous activities, such as heavy lifting and vigorous exercise, for six weeks. You should be able to try some gentle exercise, drive after two to four weeks and go back to work when you feel ready.

Losing a testicle may cause some people to feel embarrassed or depressed, or could lead to low self-esteem. It may help to talk about how you are feeling with someone you trust, such as a partner, friend or counsellor. You can also call Cancer Council on 13 11 20.

Your ability to get an erection and experience orgasm should not be affected by the removal of one testicle, but some people find it takes time to adjust. As long as the remaining testicle is healthy, losing one testicle is unlikely to affect your ability to have children (fertility). While it is rare, if you have both testicles removed, you will become infertile. Speak to your doctor before surgery if you are wanting to have children in the future.

Having a prosthesis

You may decide to replace the removed testicle with an artificial one called a prosthesis. The prosthesis is a silicone implant similar in size and shape to the removed testicle. There are different brands, and some feel firmer than others.

Whether or not to have a prosthesis is a personal decision. If you choose to have one, you can have the operation at the same time as the orchidectomy or at another time. Your urologist can give you more information about your options.

Further tests

If the removal of your testicle and initial tests show that you have cancer, you may have further tests to see whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes or other organs. These tests may also be used during or after treatment to check how well the treatment has worked. They can include:

- CT scan – You may have a computerised tomography (CT) scan of your chest, abdomen and pelvis. Sometimes this is done before the orchidectomy. A CT scan uses x-rays to take pictures of the inside of your body and then compiles them into one detailed, cross-sectional picture.

- MRI scan – In some circumstances, such as if you have an allergy to the dye normally used for a CT scan, you may instead have a magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) scan. An MRI scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed pictures of areas inside the body.

- PET–CT scan – You may also be given a positron emission tomography (PET) scan combined with a CT scan. You will be injected with a small amount of a glucose (sugar) solution containing some radioactive material, which helps cancer cells show up more brightly on the scan.

All tests and scans have risks and benefits which you should discuss with your doctor.

Staging

The tests below will help to show whether and how far the cancer has spread (the stage). There are several staging systems for testicular cancer, but the most commonly used is the TNM system. The TNM scores and the levels of tumour markers in the blood are used to work out an overall stage for the cancer. Stage 1 means that the cancer is found only in the testicle (early-stage cancer). Stage 2 and above mean that the cancer has spread outside the testicle to the lymph nodes in the abdomen or pelvis, or to other areas of the body.

TNM staging system

| T (tumour) |

describes whether the cancer is only in the testicle (T1) or has spread into nearby blood vessels or tissue (T2, T3, T4) |

| N (nodes) |

describes whether the cancer is not in any lymph nodes (N0) or has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1, N2) |

| M (metastasis) |

describes whether cancer has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0) or whether cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes, organs or bones (M1) |

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease. To assess your prognosis, your doctor will consider:

- your test results

- the type of testicular cancer you have

- the stage of the cancer

- other factors such as your age, fitness and medical history.

Testicular cancer has the highest survival rates of any cancer (other than common skin cancers).Regular monitoring and review (surveillance) is a major factor in ensuring good outcomes, so it’s vital that you attend all your follow-up appointments (see Follow-up appointments).

Key points

- Your doctor will examine your testicles, scrotum and groin for a lump or swelling.

- An ultrasound will create a picture of your scrotum and testicles. This is a quick and painless scan.

- Blood tests will look for proteins (tumour markers) in your blood that may indicate cancer. Some people with testicular cancer do not have raised tumour marker levels.

- Some people will have a CT scan before surgery.

- In most cases, the only way to diagnose testicular cancer with certainty is to remove the testicle. This operation is called an orchidectomy. An orchidectomy is also the main treatment for testicular cancer that has not spread.

- After an orchidectomy, you will have side effects such as pain and bruising. These will ease over time. Wearing scrotal support underwear will help.

- You may choose to replace the removed testicle with a silicone implant (prosthesis).

- If the removal of the testicle shows that you have cancer, you will probably have more tests to see whether the cancer has spread.

- You will usually have a CT scan and repeat tumour marker blood tests after the orchidectomy. Some people may have other scans.

- The doctor will tell you the stage of the cancer, which describes whether and how far the cancer has spread through your body.

- Testicular cancer usually has an excellent long-term prognosis. It is very important, however, to attend regular follow-up appointments.

Understanding Testicular Cancer

Download our Understanding Testicular Cancer booklet to learn more.

Download now

Expert content reviewers:

Dr Benjamin Thomas, Urological Surgeon, The Royal Melbourne Hospital and The University of Melbourne, VIC; A/Prof Ben Tran, Genitourinary Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and The University of Melbourne, VIC; Dr Nari Ahmadi, Urologist and Urological Cancer Surgeon, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; Helen Anderson, Genitourinary Cancer Nurse Navigator, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD; Anita Cox, Youth Cancer – Cancer Nurse Coordinator, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD; Dr Tom Ferguson, Medical Oncologist, Fiona Stanley Hospital, WA; Dr Leily Gholam Rezaei, Radiation Oncologist, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, NSW; Dheeraj Jain, Consumer; Amanda Maple, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA; Jessica Medd, Senior Clinical Psychologist, Department of Urology, Concord Repatriation General Hospital and Headway Health, NSW.

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Testicular Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2023 edition). This webpage was last updated in August 2023.