Page last updated: February 2025

The information on this webpage has been adapted from Understanding Targeted Therapy - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2025 edition). This webpage was last updated in February 2025.

Expert content reviewers:

This information was developed with help from a range of health professionals and people affected by cancer who have had targeted therapy. We thank the reviewers of this booklet:

- A/Prof Rohit Joshi, Medical Oncologist, Calvary Central Districts and Lyell McEwin Hospital, and Director, Cancer Research SA

- Jenny Gilchrist, Nurse Practitioner – Breast Oncology, Macquarie University Hospital, NSW

- Jon Graftdyk, Consumer

- Sinead Hanley, Consumer

- Lisa Hann, 13 11 20 Consultant, SA

- Dr Malinda Itchins, Thoracic Medical Oncologist, Royal North Shore Hospital and Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW

- Gay Refeld, Clinical Nurse Consultant, Breast Care, St John of God Subiaco Hospital, WA

- Prof Benjamin Solomon, Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Helen Westman, Lung Cancer Nurse Consultant, Respiratory Medicine and Sleep Department, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW

Targeted therapy is a drug treatment that targets specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading.

The drugs circulate through the body like chemotherapy but they work in a more focused way and may have fewer side effects than chemotherapy. However, targeted therapy does not work for all cancer types or all people.

How targeted therapy works

The body constantly makes new cells to help us grow, replace worn-out tissue and heal injuries. Healthy cells multiply and die in an orderly way. Cancer cells are different – they multiply faster and keep growing.

This happens because of changes in the genes of the cancer cells. These gene changes affect the proteins that allow the cancer cells to grow and survive; they also create features within or on the surface of the cancer cells that can be targeted.

Each targeted therapy drug acts on a particular feature of the cancer cell. Your doctor may call this the “molecular target”. The drug will only be given if tests show that the cancer cells have the target.

Targeted therapy may kill the cancer cells or slow their growth, causing the signs and symptoms of cancer to reduce or disappear. These drugs often have to be taken long term, but many people continue their usual activities and enjoy a good quality of life.

Who can have targeted therapy?

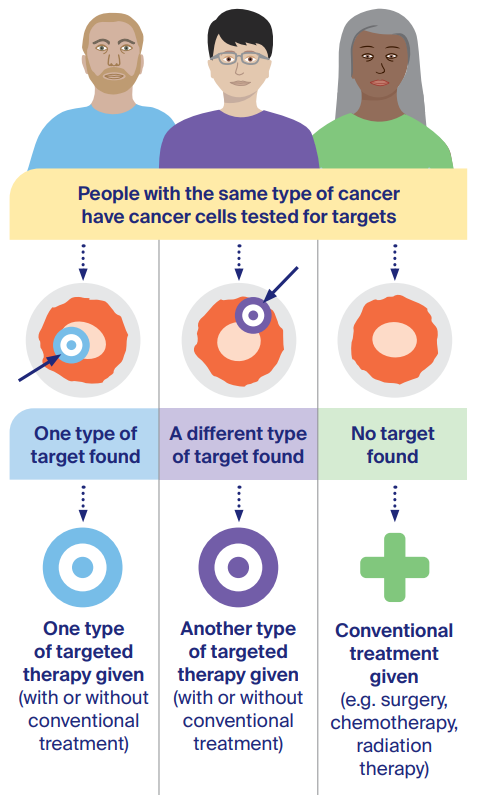

For some types of cancer, your doctor will test a tissue sample to see if the cells contain a particular target that is allowing the cancer to grow. People with the same cancer type may be offered different treatments based on their test results.

The chance of having cancer cells with a suitable target for a particular targeted therapy may be much higher or lower depending on the type of cancer.

How cancer is treated

Because each cancer is unique, people may have different treatment plans, even if they have the same type of cancer. The three most common cancer treatments are:

Other treatments used for some types of cancer include:

Targeted therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and hormone therapy are different types of drug therapy. They are known as systemic treatment because the drugs circulate and kill cancer cells throughout the body.

Cancer treatments may be used on their own or in combination. For example, you may have surgery to remove a tumour, followed by targeted therapy to stop the cancer returning. Sometimes, targeted therapy is combined with chemotherapy.

Doctors will recommend the best treatment for you based on the type and stage of cancer, its genetic make-up, your age and your general health.

How targeted therapy differs from chemotherapy

Targeted therapy and chemotherapy are both types of systemic treatment, but they work in different ways.

Chemotherapy drugs affect all cells that multiply quickly. This means the drugs can kill cancer cells and also damage other cells that multiply quickly, such as healthy cells in the mouth, stomach, bone marrow or hair.

This is why chemotherapy side effects may include mouth ulcers, nausea, low numbers of blood cells (leading to infections or anaemia) and hair loss.

Targeted therapy drugs focus on the cancer cells, while limiting damage to healthy cells.

Many people experience fewer side effects with targeted therapy. Some side effects, however, can be serious. Sometimes, the target is on healthy cells as well as cancer cells, and this can lead to particular side effects.

For example, the EGFR gene may be on healthy skin cells as well as the cancer cells, so the targeted therapy can cause a rash.

When it is used

Using targeted therapy to treat cancer has improved survival rates for several types of cancer, and many people respond well. However, targeted therapy is not an option for everyone with cancer.

In Australia, targeted therapy drugs are now available for a range of cancers, including:

- blood cancers such as leukaemia and lymphoma;

- common cancers such as bowel, breast, lung and melanoma; and

- other cancers such as cervical, head and neck, kidney, liver, ovarian, sarcoma, stomach and thyroid.

For most of these cancers, targeted therapy is available only when the cancer is advanced. For some types, however, it may also be available for early-stage cancer to improve the chance of a good outcome.

New drugs are becoming available all the time. Talk to your doctor about the latest options. Targeted therapy may be used:

- before surgery to reduce the size of a cancer (neoadjuvant therapy)

- after surgery to destroy any remaining cancer cells (adjuvant therapy)

- to treat cancer after initial treatments if the cancer has come back (recurrent disease) or hasn’t responded to other treatments

- as initial treatment for advanced cancer that has certain gene changes

- as long-term treatment to try to prevent the cancer coming back or growing (called maintenance treatment).

Most targeted therapy drugs are not safe to use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Ask your doctor for advice about contraception.

If you may want to have children in the future, talk to your doctor about your options (e.g. storing sperm or eggs) before starting targeted therapy. If you become pregnant while taking targeted therapy, let your medical team know immediately.

Will it work?

The cancer must contain the particular target or the drug won’t work. The response to targeted therapy varies widely. In some cancers, four out of five people assessed as suitable for a particular targeted therapy drug will respond.

For other cancers, the rate of success is much lower. This is due to a range of factors, including how many of the cancer cells carry the target.

Cancer cells can eventually stop responding to a targeted therapy drug even if it works at first. If this happens, you may be offered another targeted therapy drug or a different type of treatment.

Less commonly, a targeted therapy drug may cause serious side effects and the treatment plan will need to be adjusted (e.g. a lower dose or different drug may be tried).

Knowing if it is working

You will have regular check-ups with your doctor, blood tests and different types of scans to see whether the cancer has responded to treatment with targeted therapy.

A good response from targeted therapy will make a cancer shrink or even disappear completely from scans. In some cases, the cancer remains stable, which means it doesn’t grow in size on scans, but also does not shrink or disappear.

People with stable disease can live for a long time and have a good quality of life.

Access and cost

Ask your cancer specialist if there is a suitable targeted therapy for you. This will depend on the type and stage of the cancer.

Your specialist may also need to test the cancer to see if one of the currently available drugs is an option. If you have not already had surgery or a biopsy, you may need to have a biopsy so a tissue sample can be collected.

Many more targeted therapy and other new drugs are being studied in clinical trials. Talk with your specialist about the latest developments and whether there are any trials that might be right for you.

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) covers most of the cost of many prescription medicines, including some targeted therapy drugs.

Medicines not on the PBS are usually expensive, but you may be able to receive them as part of a clinical trial or at a reduced cost through a compassionate access program.

Question checklist

It is important to ask your specialist questions, especially if you feel confused or uncertain about your treatment. If you have a lot of questions, you could also talk to a cancer care coordinator or nurse.

You may want to make a list of questions before appointments and include some of these questions:

- Is targeted therapy available as part of my treatment plan? If not, why not?

- Which targeted therapy drug are you recommending? Does it have different names?

- Will it be my only treatment, or will I also have other treatments?

- How much will targeted therapy cost? Is there any way to reduce the cost if I can’t afford it?

- Are there any clinical trials that would give me access to new types of targeted therapy?

- How often am I likely to have targeted therapy?

- How long will I receive targeted therapy?

- Where will I have targeted therapy? Will I need to come to the hospital or treatment centre for an IV infusion or injection, or will I be taking tablets or capsules at home?

- If I am taking the treatment at home, can I get the prescription filled at any pharmacy?

- What should I do if the pharmacy cannot fill my prescription?

- Do I have to be careful with over-the-counter medicines or supplements? What food/drinks should I avoid while taking targeted therapy?

- What should I do if I forget to take the targeted therapy drug?

- What side effects should I watch out for or report?

- Who do I contact if I get side effects?

- How can side effects be managed?

- Will the drugs affect my immune system?

- Can I still have vaccinations?

How it is given

Targeted therapy is usually prescribed by a medical oncologist or haematologist. It may be given on its own or combined with chemotherapy or other types of cancer drugs.

Some targeted therapy drugs are given in repeating cycles, with rest periods in between. Others are taken every day without any breaks.

Cancer treatments are usually given in line with protocols that set out which drugs to have, how much and how often. Your specialist may need to adjust the protocols to your individual situation.

Targeted therapy is given in different ways:

- as tablets or capsules that you can swallow

- as an intravenous (IV) infusion into a vein, either through a drip in your arm or into a port (a small device inserted under the skin of the chest or arm)

- as an injection under the skin.

Reactions and precautions

When targeted therapy is given as an infusion, some people react to the infusion process (e.g. skin rashes, nausea, difficulty breathing). Reactions can occur during the infusion or several hours afterwards.

You will be monitored and may be given medicines to help prevent this. Reactions are more common with the first couple of infusions, so they may be given at a slower rate than later treatments.

How long you have targeted therapy depends on the aim of the treatment, how the cancer responds and any side effects you may have.

In many cases, targeted therapy tablets or capsules need to be taken daily for many months or even years. Your treatment team can give you more details.

In some cases, you may need to take special precautions to protect other people in your household while you are having targeted therapy. Talk to your doctor about any safety measures that you may need to take.

Possible side effects

Although targeted therapy does less damage to healthy cells, it can still have side effects. These vary for each person. Some people have only a few mild side effects, while others may have more.

Skin problems are a common side effect of targeted therapy. Different drugs may cause:

- sensitivity to sunlight, skin redness, swelling and dry, flaky skin

- a rash that looks like acne or pimples on the face, scalp or upper body (acneiform rash)

- a skin reaction on the palms and soles, which may include redness, burning, pain, skin peeling and blistering, and thickened skin (called hand–foot syndrome).

Other side effects may include fever, tiredness, joint aches, nausea, headaches, dry or itchy eyes with or without blurred vision, diarrhoea and constipation, bleeding and bruising, and high blood pressure.

Less commonly, some targeted therapy drugs can affect the way the heart, thyroid or liver work, or increase the risk of getting an infection. It may also cause inflammation of the lungs (pneumonitis). If left untreated, some side effects can become serious.

Managing side effects

Targeted therapy side effects can begin within days of starting treatment, but more often they occur weeks or even months later.

Most side effects are temporary, lasting from a few weeks to a few months, and will gradually improve over time or once you stop taking the drug. In rare cases, however, some side effects may be permanent.

Your treatment team can help you manage any side effects of targeted therapy, which often need a different approach to side effects from other cancer treatments.

For example, skin problems from targeted therapy may be more severe or last longer than skin problems from chemotherapy, and you may be prescribed an antihistamine or steroid cream to help with the itching and dryness.

In some cases, your treatment team will modify the dose of the targeted therapy drug to see if that helps ease the side effects.

Reporting side effects

Some rare side effects, such as heart and lung problems, can become serious and even life-threatening if not treated. It is important to tell your treatment team about any new or worsening side effects.

Ask the doctor or nurse which side effects to look out for or report, and who to contact (including after hours).

Some people worry about telling their doctor about side effects because they don’t want to stop the treatment, but most side effects can be better managed when they are reported early.

Your doctor may be able to prescribe medicine to prevent or reduce side effects. In some cases, you may need to take a break from treatment to prevent side effects becoming too serious and causing long-term damage.

Often, when side effects are managed before they become too severe, treatment can continue again once things have improved. At times, taking the drug at a lower dose will still be effective and can prevent the side effects from returning.

Targeted therapy drugs can interact with many common medicines and cause harmful side effects.

It is important to let your doctor know about any other medicines or vitamin or herbal supplements you are taking so they can check for any known problems. It is also a good idea to talk with your cancer specialist before having any vaccinations.

Types of targeted therapy drugs

There are many different types of targeted therapy drugs. They are put into groups based on how they work. The two main groups are:

Monoclonal antibodies

The body’s immune system makes proteins called antibodies to help fight infections. Monoclonal antibodies are manufactured (synthetic) versions of these natural antibodies.

They lock onto a protein on the surface of cells or surrounding tissues to affect how cancer cells grow and survive. Types include:

-

- angiogenesis inhibitors – reduce the blood supply to a tumour to slow or stop it growing.

- HER2-targeted agents – target the protein HER2, which cause cancer cells to grow uncontrollably.

- anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies – target the protein CD20 found on some B-cell leukaemias and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

- antibody drug conjugates – target the cancer with a high dose of chemotherapy without damaging healthy cells.

Some monoclonal antibodies are also classified as immunotherapy because they use the immune system to fight cancer.

Small molecule inhibitors

These drugs are small enough to get inside cancer cells and block certain proteins that tell cancer cells to grow. Types include:

- TKIs – block proteins called tyrosine kinases from sending signals that tell cancer cells to grow, multiply and spread.

- mTOR inhibitors – block mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a protein that tells cancer cells to grow and spread.

- PARP inhibitors – block poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), a protein that repairs damaged DNA in cancer cells.

- CDK inhibitors – block cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) from sending signals that tell cancer cells to grow, multiply and spread.

New drugs become available every year, so talk to your cancer specialist for the latest information.

“When I was first diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia, I was put on imatinib. I had severe side effects, so my haematologist put me on dasatinib. I’ve been on this for over 8 years with excellent results. As the leukaemia is still detected in blood tests, there’s no plan to discontinue the treatment.” Patricia

Gene changes and cancer cells

Genes are made up of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). Each human cell has about 20,000 genes, and most genes come in pairs, with one copy inherited from each parent.

As well as telling the cell what to do and when to grow and divide, genes provide the recipe for cells to make proteins. These proteins carry out specific functions in the body.

When a cell divides, it makes a copy of itself, including all the genes it contains. Sometimes copying mistakes can happen, causing changes (mutations or alterations) in the genes.

If these mistakes affect the genes that tell the cell what to do, a cancer can grow. Most gene changes that cause cancer build up during a person’s lifetime (acquired gene changes).

Some people are born with a gene change that increases their risk of cancer (an inherited faulty gene, also known as hereditary cancer syndrome).

Only about 5% of cancers are caused by an inherited faulty gene. Targeted therapy drugs may act on targets from either acquired or inherited gene changes.

Testing for targeted therapy

To find out if the cancer contains a gene change that may respond to a particular targeted therapy drug, your doctor will take a sample from the cancer or your blood, and send it to a laboratory for testing.

It may take from a few days to a few weeks to receive the results. The testing may find specific mistakes in that cancer, whether they are acquired gene changes found only in the cancer cells, or inherited changes that are also present in normal cells.

The testing may involve a simple test known as staining, or more complex tests known as genomic or molecular testing.

Family testing

If the cancer contains a faulty gene that may be linked to a hereditary cancer syndrome, or if your personal or family history suggests a hereditary cancer syndrome, your doctor will refer you to a family cancer service or genetic counsellor.

They may suggest genetic testing. Knowing that you have inherited a faulty gene may help your doctor work out what treatment to recommend.

It could also allow you to consider ways to reduce the risk of developing other cancers, and it is important information for your blood relatives.

Medicare rebates are available for some genetic tests. You may need to meet certain eligibility requirements. Visit the Health Centre for Genetics Education for more information and to find a public family cancer clinic.