Page last updated: March 2024

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Vulvar Cancer - A guide for people affected by cancer (2023 edition). This webpage was last updated in March 2024.

Expert content reviewers:

This information was developed with the help of a range of health professionals and people affected by secondary bone cancer:

- Dr Craig Lewis, Conjoint Associate Professor UNSW, Senior Staff Specialist, Department of Medical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, NSW

- Dr Katherine Allsopp, Staff Specialist, Palliative Medicine, Westmead Hospital, NSW

- Michael Coulson, Consumer

- Caitriona Nienaber, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA

- David Phelps, Consumer

- Juliane Samara, Nurse Practitioner Specialist Palliative Care, Clare Holland House, Calvary Public Hospital Bruce, ACT

- A/Prof Robert Smee, Radiation Oncologist, Nelune Cancer Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital, NSW.

About the vulva

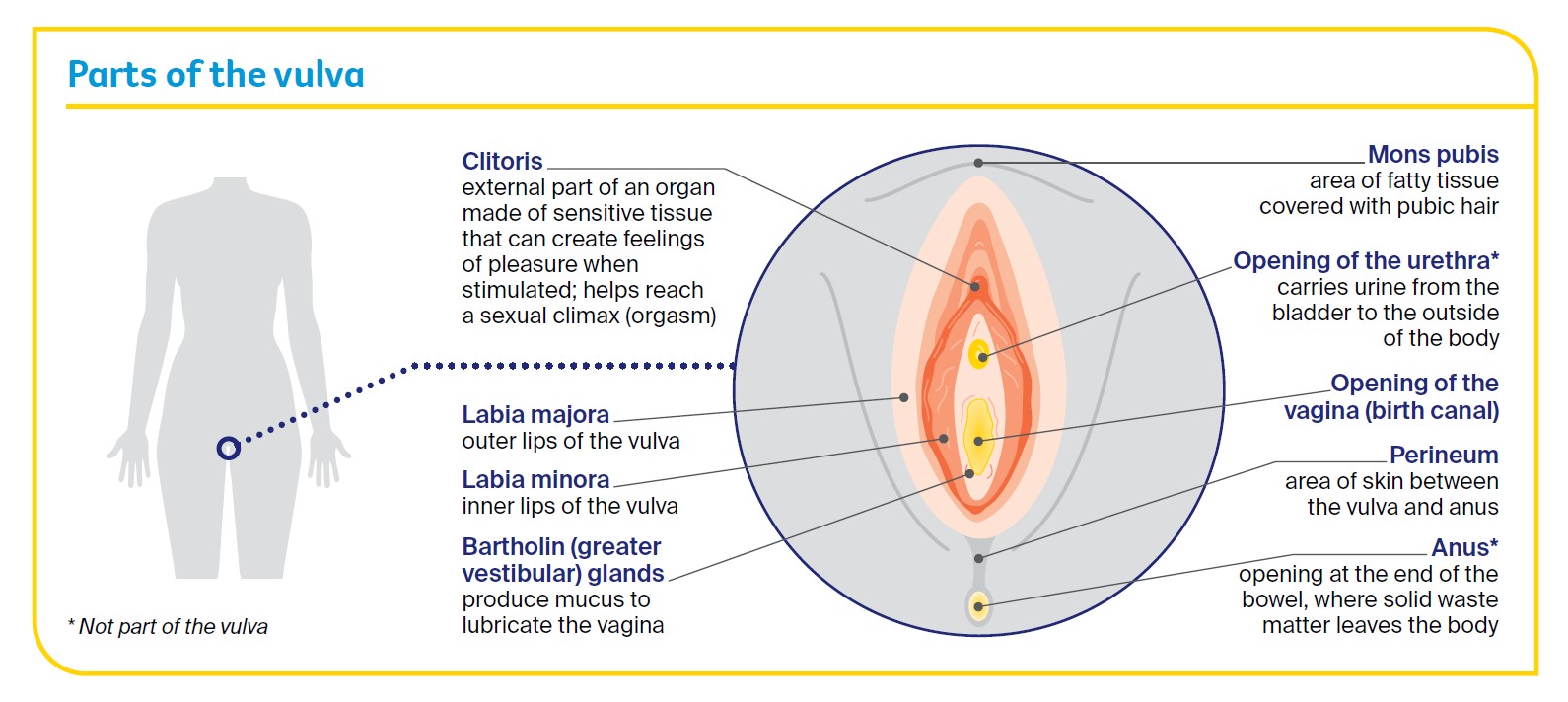

The vulva is a general term for a female’s external sexual organs (genitals). The main parts of the vulva are shown in the diagram below.

What is vulvar cancer?

Vulvar cancer is the abnormal growth of cells in any part of the vulva. It is also called vulval cancer or cancer of the vulva. It most commonly develops in the skin of the labia majora, labia minora and the perineum.

Less often, it involves the clitoris, mons pubis or Bartholin glands.

As the cancer grows, it can spread to areas near the vulva, such as the vagina, bladder or anus.

How common is vulvar cancer?

Vulvar cancer is rare – about 420 women are diagnosed each year in Australia. It is more likely to affect women who have gone through menopause (stopped having periods), but it can occur at any age.

Anyone with a vulva can get vulvar cancer – women, transgender men, non-binary people and intersex people.

For more information, speak to your doctor or see LGBTQI+ People and Cancer.

Main types of vulvar cancer

The main types of vulvar cancer are:

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

- Vulvar (Mucosal) Melanoma

The types of vulvar cancer are named after the cells they start in.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma is the most common type of vulvar cancer, making up abour nine out of 10 cases. SCC starts in thin, flat (squamous) skin cells covering the surface of the vulva. Verrucous carcinoma is a rare subtype that looks like a large wart and grows slowly

Vulvar (Mucosal) Melanoma makes up less than one out of 10 cases of vulvar cancer, and starts in skin cells (melanocytes) found in the lining of the vulva.

There are also rarer types of vulvar cancer. These include:

- sarcomas

- adenocarcinomas

- Paget disease of the vulva

- basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).

Vulvar cancer risk factors

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Many cases of vulvar cancer are caused by infection with HPV, which is a very common virus in people who are sexually active. HPV often causes no symptoms.

Only some types of HPV cause cancer, and most people with HPV don’t develop vulvar or any other type of cancer.

It can be many years between infection with HPV and the first signs of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) or vulvar cancer.

Learn more

Vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL)

Having vulvar SIL increases the risk of developing vulvar cancer. This condition changes the vulvar skin, and may cause itching, burning or soreness.

Other risk factors

- the skin conditions vulvar lichen planus, vulvar lichen sclerosus or extramammary Paget disease

- having had an abnormal cervical screening test or cancer of the cervix or vagina

- smoking tobacco (which can make cancer more likely to develop in people with HPV). Call Quit 13 7848 for help quitting.

- being aged over 70 (a little over half of all vulvar cancers are in women over 70)

- having a weakened immune system.

Finding support

When you call the Cancer Council support line on 13 11 20, you’ll talk to a cancer nurse and get the support you need.

It’s free, confidential, and available for anyone affected by cancer who has a question – those diagnosed as well as their family, friends, and carers.

Contact cancer support

Vulvar cancer symptoms

Early vulvar cancer often has no obvious symptoms. It is commonly diagnosed after having vulvar symptoms for months or years. These may include:

- an ulcer that won’t heal

- a lump, sore, swelling or wart-like growth

- itching, burning and soreness or pain in the vulva

- thickened, raised skin patches (may be red, white or dark brown)

- a mole on the vulva that changes shape or colour

- blood, pus or other discharge coming from an area of skin or a sore spot in the vulva (not related to your menstrual period)

- hard or swollen lymph nodes in the groin area.

Many women don’t look at their vulva, so they don’t know what is normal for them. The vulva can be difficult to see without a mirror, and you may feel uncomfortable examining your genitals.

If you feel any pain in your genital area or notice any of these symptoms, visit your general practitioner (GP) so they can examine the area you are concerned about. Don’t let embarrassment stop you getting checked.

Precancerous vulvar cell changes

Sometimes the squamous cells in the vulva start to change. These changes may be precancerous. This means there is an area of abnormal tissue (a lesion) in the vulva that is not cancer, but may develop into cancer over time if left untreated.

These lesions are called vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). They can be classified as:

- low grade (LSIL), which may go away without treatment and is linked to human papillomavirus (HPV)

- high grade (HSIL), which may develop into vulvar cancer and is linked to HPV

- differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), which may develop into vulvar cancer and is not usually linked with HPV but is linked with the skin condition lichen sclerosus.

Most cases of vulvar SIL don’t develop into vulvar cancer. Your doctor will explain the treatment options suitable for you.

Understanding Vulvar Cancer

Download our Understanding Vulvar Cancer fact sheet to learn more and find support

Download now Order for free