About the vagina

Sometimes called the birth canal, the vagina is a muscular tube about 7-10 cm long that extends down from the cervix to the vulva (external genitals). The vaginal opening is where menstrual blood flows out of the body, sexual intercourse occurs, and a baby leaves the body.

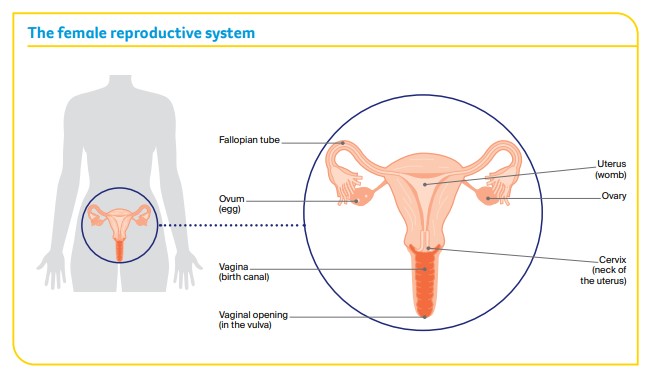

The vagina is part of the female reproductive system, which also includes the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vulva.

Vaginal cancer

Cancer in the vagina can be either a primary or secondary cancer. The two types of cancer are different and are often treated differently.

Vaginal cancer is one of the rarest types of cancer affecting the female reproductive system (gynaecological cancer). About 120 women are diagnosed with vaginal cancer each year in Australia.

Anyone with a vagina can get vaginal cancer – women, transgender men, non-binary people and intersex people. For more information, speak to your doctor or see LGBTQI+ People and Cancer.

Primary vaginal cancer

This is cancer that starts in the vagina. The two main types of primary vaginal cancer are named after the cells they start in.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- starts in thin, flat (squamous) skin cells lining the vagina

- most common type (about 9 out of 10 cases)

Adenocarcinoma

- develops from the mucusproducing (glandular) cells in the vagina

- includes clear cell carcinoma

- less common type (less than 1 out of 10 cases)

There are also rarer types of vaginal cancer. These include melanomas, which start in skin cells called melanocytes; sarcomas, which start in the muscle; and lymphomas, which start in the white blood cells.

Secondary vaginal cancer

This is cancer that has spread (metastasised) to the vagina from a primary cancer in another part of the body, such as the cervix, uterus, vulva, bladder or bowel. Secondary vaginal cancer is much more common than primary vaginal cancer. For information about secondary vaginal cancer, speak to your treatment team.

Precancerous vaginal cell changes

Sometimes the squamous cells in the lining of the vagina start to change. These changes may be precancerous. This means there is an area of abnormal tissue (a lesion) in the vagina that is not cancer, but may develop into cancer over time if left untreated.

These lesions are called squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL), which used to be known as vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). Lesions can be classified as either:

- low grade (LSIL), which may go away without treatment

- high grade (HSIL), which may develop into vaginal cancer if left untreated.

SIL usually has no symptoms and is often caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). Most cases of SIL don’t develop into vaginal cancer. Your doctor will explain the treatment options suitable for you.

Cancer of the neovagina

Some people choose to have surgery to create a vagina. This is called a neovagina and it may use tissue from the vulva, penis or abdominal wall, or from the bowel.

A cancer can develop in a neovagina, but it is exceptionally rare. This is not primary vaginal cancer, but cancer that develops in the tissue used to create the neovagina.

If you have a neovagina, talk to your doctors about appropriate follow-up examinations and signs to look out for.

Risk factors

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Many cases of vaginal cancer are caused by infection with HPV, which is a very common virus in people who are sexually active. About 4 out of 5 people will become infected with one type of genital HPV at some time in their lives. HPV often causes no symptoms. Only some types of HPV cause cancer, and most people with HPV don’t develop vaginal or any other type of cancer. It can be many years between infection with HPV and the first signs of HSIL or vaginal cancer.

Other risk factors

Although HPV infection and vaginal HSIL are the main risk factors, other things that increase the risk include:

- previously having HSIL of the cervix or cervical cancer

- smoking tobacco (which can make cancer more likely to develop in people with HPV)

- being aged over 70 (almost half of all vaginal cancers are in women over 70)

- having a weakened immune system

- exposure to a drug called diethylstilbestrol (DES), which was prescribed to pregnant women from the 1940s to the early 1970s to prevent miscarriage. The female children of women who took DES have a small but increased risk of developing clear cell carcinoma of the vagina.

Symptoms

Early vaginal cancer often has no obvious symptoms. If symptoms do occur, they most often include:

- bloody vaginal discharge (not related to your menstrual period)

- pain during sexual intercourse

- bleeding after sexual intercourse

- a lump in the vagina.

Rarer symptoms include pain in the pelvic area or rectum; and bladder problems, such as blood in the urine (wee) or passing urine often or during the night.

Not everyone with these symptoms has vaginal cancer. If you have any ongoing symptoms, make an appointment to see your general practitioner (GP). Don’t let embarrassment stop you getting checked.

Understanding Vaginal Cancer

Download our Understanding Vaginal Cancer fact sheet to learn more and find support

Download now Order for free

Expert content reviewers:

Prof Alison Brand, Director, Gynaecological Oncology, Westmead Hospital, NSW; Gemma Busuttil, Radiation Therapist, Crown Princess Mary Cancer Centre, Westmead Hospital, NSW; Kim Hobbs, Clinical Specialist Social Worker, Gynaecological Cancer, Westmead Hospital, NSW; Dr Ming-Yin Lin, Radiation Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Dr Lisa Mackenzie, Clinical Psychologist Registrar, HNE Centre for Gynaecological Cancer, Hunter New England Local Health District, NSW; Anne Mellon, CNC – Gynaecological Oncology, HNE Centre for Gynaecological Cancer, Hunter New England Local Health District, NSW; A/Prof Tarek Meniawy, Medical Oncologist, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital and The University of Western Australia, WA; Dr Archana Rao, Gynaecological Oncologist, Senior Staff Specialist, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD; Tara Redemski, Senior Physiotherapist – Cancer and Blood Disorders, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD; Angela Steenholdt, Consumer; Maria Veale, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council QLD.

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Vaginal Cancer (2023 edition). This webpage was last updated in October 2023.