Page last updated: April 2024

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Thyroid Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2020 edition). This webpage was last updated in April 2024.

Expert content reviewers:

This information was developed based on international clinical practice guidelines and with help from a range of health professionals and people affected by thyroid cancer:

- A/Prof Diana Learoyd, Endocrinologist, Northern Cancer Institute, and Northern Clinical School, The University of Sydney, NSW

- Dr Gabrielle Cehic, Nuclear Medicine Physician and Oncologist, South Australia Medical Imaging (SAMI), and Senior Staff Specialist, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, SA

- Dr Kiernan Hughes, Endocrinologist, Northern Endocrine and St Vincents Hospital, NSW

- Yvonne King, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council NSW

- Dr Christine Lai, Senior Consultant Surgeon, Breast and Endocrine Surgical Unit, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, and Senior Lecturer, Discipline of Surgery, University of Adelaide, SA

- A/Prof Nat Lenzo, Nuclear Physician and Specialist in Internal Medicine, Group Clinical Director, GenesisCare Theranostics, and The University of Western Australia, WA

- Ilona Lillington, Clinical Nurse Consultant (Thyroid and Brachytherapy), Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane Women’s Hospital, QLD

- Jonathan Park, Consumer.

What is thyroid cancer?

Thyroid cancer develops when the cells of the thyroid grow and divide in an abnormal way.

The thyroid

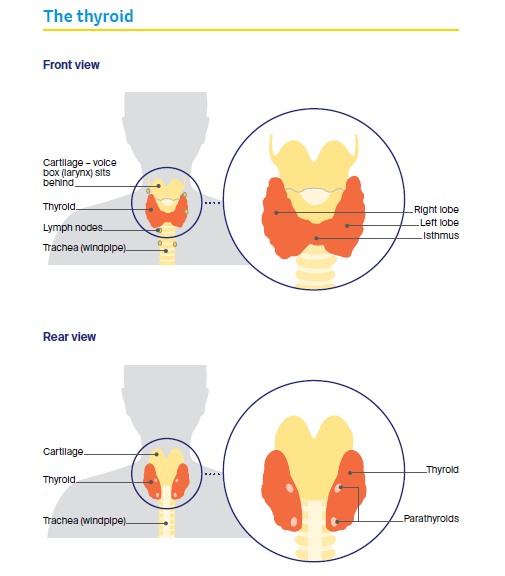

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland found at the front of the neck and just below the voice box (larynx). It has two halves, called lobes, which lie on either side of the windpipe (trachea).

The lobes are connected by a small band of thyroid tissue known as the isthmus. There are two main types of cells in the thyroid:

- follicular cells – produce and store the hormones T4 and T3, and make a protein called thyroglobulin (Tg)

- parafollicular cells (C-cells) – produce the hormone calcitonin.

The role of the thyroid

The thyroid is part of the endocrine system, which is a group of glands that makes and controls the body’s hormones.

The thyroid makes two hormones (T4 and T3) that control the speed of the body’s processes, such as heart rate, digestion, body temperature and weight. This speed is known as your metabolic rate.

The thyroid also produces the hormone calcitonin, which plays a role in controlling the body’s calcium levels.

The role of thyroid hormones

The hormones T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (tri-iodothyronine) are known as the thyroid hormones. To make these hormones, the thyroid needs iodine, which is found in a range of foods such as seafood and iodised salt.

To keep the body working properly, it is important that the thyroid makes the right amounts of T4 and T3. This is controlled by the pituitary gland, which is located at the base of the brain.

Changes in thyroid hormone levels affect your metabolism by slowing down or speeding up the body’s processes.

Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism)

If you don’t have enough thyroid hormones, your metabolism slows down. As a result, you may feel tired or depressed, and gain weight easily.

Other symptoms may include difficulty concentrating, constipation, brittle and dry hair and skin, sluggishness and fatigue. In severe cases, heart problems could occur.

Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism)

If you have too many thyroid hormones, your metabolism speeds up. As a result, you may lose weight, have increased appetite, feel shaky and anxious, or have rapid, strong heartbeats (palpitations).

Over time, untreated hyperthyroidism can result in loss of bone strength and problems with heart rhythm.

Types of thyroid cancer

There are several types of thyroid cancer. It is possible to have more than one type at once, although this is unusual.

- papillary (about 70-80% of all thyroid cancer cases) – develops from the follicular cells and tends to grow slowly.

- follicular (about 10% of all thyroid cancer cases) – develops from the follicular cells and includes Hürthle cell carcinoma, a less common subtype.

- medullary (about 6% of all thyroid cancer cases) – develops from the parafollicular cells. It can run in families and may be associated with tumours in other glands.

- oncocytic (about 3% of all thyroid cancer cases) - develops from thyroid follicles. Also known as oxyphilic or Hürthle cell carcinoma.

- anaplastic (about 1% of all thyroid cancer cases) – may develop from papillary or follicular thyroid cancer. It tends to grow quickly and usually occurs in people over 60 years old.

How common is thyroid cancer?

About 2900 people are diagnosed with thyroid cancer each year in Australia. Thyroid cancer can occur at any age.

It affects almost three times as many women as men – it is the seventh most common cancer affecting Australian women of all ages, and the most common cancer diagnosed in women aged 20–24.

Diagnoses of thyroid cancer in Australia have increased in recent years, with almost four times as many cases estimated in 2019 as there were in 1982.

Some of this increase is due to the improved quality and greater use of diagnostic scans, such as ultrasounds.

This has led to the detection of smaller, often insignificant, thyroid cancers that would otherwise not have been found.

Learn more

Signs and symptoms

Thyroid cancer usually develops slowly, without many obvious symptoms. However, some people experience one or more of the following:

- a painless lump in the neck (the lump may grow gradually)

- trouble swallowing

- difficulty breathing

- changes to the voice, e.g. hoarseness

- swollen lymph glands (lymph nodes) in the neck (the lymph nodes may slowly grow in size over months or years).

Although a painless lump in the neck is a typical sign of thyroid cancer, thyroid lumps are common and turn out to be benign in 90% of adults. Having an underactive or overactive thyroid is not typically a sign of thyroid cancer.

“Sometimes I felt people were a little dismissive because thyroid cancer has a good outlook. They would say, ‘If you’re going to get cancer, that’s the best type to get’. But I didn’t find this very helpful. Hearing the word ‘cancer’ made me feel gutted and afraid.” Jenny

Risk factors

The cause of thyroid cancer is unknown, but some factors are known to increase the risk of developing it. Having a risk factor does not necessarily mean that you will develop thyroid cancer. Most people with thyroid cancer have no known risk factors.

Exposure to radiation

A small number of thyroid cancers are due to having radiation therapy to the head and neck area as a child or living in an area with high levels of radiation, such as the site of a nuclear accident.

Thyroid cancer usually takes 10–20 years to develop after significant radiation exposure.

Family history

Only around 5% of thyroid cancer runs in families. Having a parent, child or sibling with papillary thyroid cancer may increase your risk.

Some inherited genetic conditions, such as familial adenomatous polyposis or Cowden syndrome, may also increase your risk of developing papillary thyroid cancer.

Most cases of medullary thyroid cancer do not run in families. However, some people inherit a faulty gene called the RET gene. This gene can cause familial medullary thyroid cancer (FMTC) or multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN).

If you are concerned about having a strong family history of thyroid cancer, talk to your doctor. They may refer you to a genetic counsellor or a family cancer clinic to assess your risk.

Other factors

People who are overweight or obese possibly have a higher risk of developing thyroid cancer.

Other thyroid conditions, such as thyroid nodules, an enlarged thyroid (known as a goitre) or inflammation of the thyroid (thyroiditis), only slightly increase the chance of developing thyroid cancer.

Studies have also linked having too much and too little iodine with a possible higher risk of thyroid cancer.

Health professionals

Your general practitioner (GP) will organise the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist, such as an endocrinologist or endocrine surgeon, who will arrange further tests.

If thyroid cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

During and after treatment you will see a range of health professionals, which may include an ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgeon, nuclear medicine specialist, head and neck surgeon, radiation oncologist and counsellor.

The health professionals you see will depend on whether the cancer has spread.