Page last updated: July 2025

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Thyroid Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2025 edition). This webpage was last updated in July 2025

Expert content reviewers:

This information was developed with help from a range of health professionals and people affected by thyroid cancer:

- A/Prof Diana Learoyd, Endocrinologist, GenesisCare North Shore, St Leonards and University of Sydney, NSW

- Sally Brooks, Senior Pharmacist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Monica Kwaczynski, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA

- Susan Leonard, Clinical Nurse Consultant – Thyroid Cancer, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD

- Juliette O’Brien OAM, Consumer

- Jonathan Park, Consumer

- A/Prof Robert Parkyn, Breast and Endocrine Surgeon, St Andrew’s Hospital and The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, SA

- A/Prof David Pattison, Director, Department of Nuclear Medicine and PET Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD

What is thyroid cancer?

Thyroid cancer happens when abnormal cells grow uncontrollably, and form a lump or tumour. There are different types of thyroid cancer. Some grow slowly and others grow quickly.

In rare cases, you can have more than one type of thyroid cancer at once. Benign thyroid nodules, also called adenomas, are not cancer.

Types of thyroid cancer

Common

- papillary – about 80% of all thyroid cancer cases, develops from the follicular cells and tends to grow slowly.

- follicular – about 10% of all thyroid cancer cases , develops from the follicular cells.

Rare

- medullary – about 6% of all thyroid cancer cases and develops from the parafollicular cells (C-cells). Can run in families and may be associated with tumours in other glands.

- oncocytic – about 3% of all thyroid cancers, also called oxyphilic or Hürthle cell carcinoma and develops from the follicular cells.

- anaplastic – about 1% of all thyroid cancer cases and develops from papillary or follicular thyroid cancer. Grows quickly and is usually found in people aged over 60.

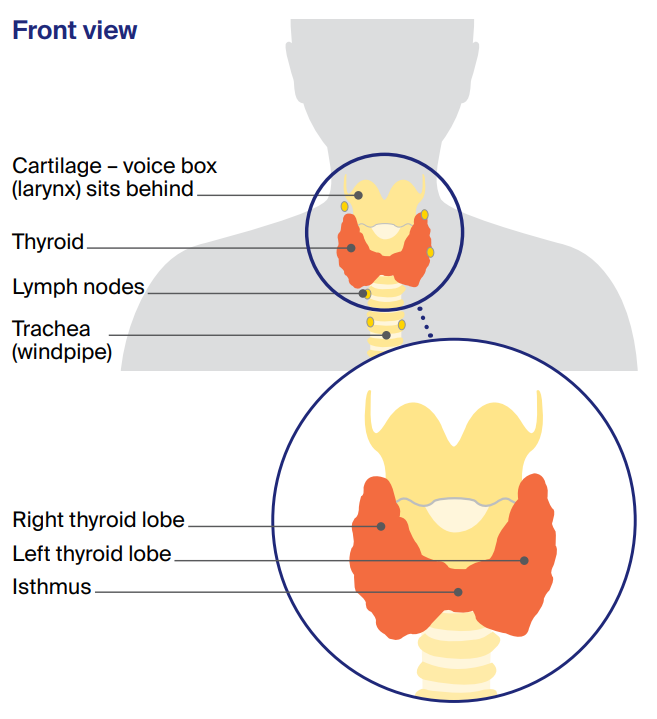

The thyroid

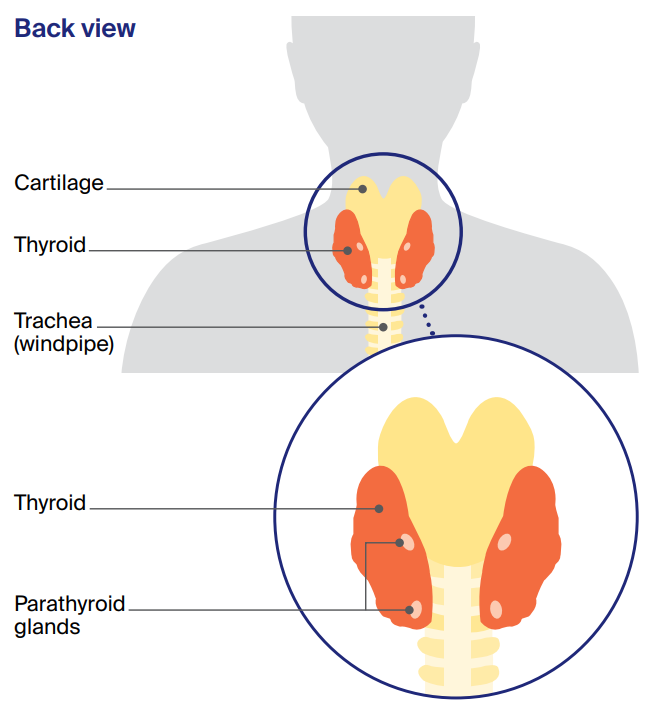

This butterfly-shaped gland sits at the front of the throat. The thyroid has two halves, called lobes. These two lobes sit on either side of the windpipe (trachea), just below the voice box (larynx).

The lobes are connected by a small band of thyroid tissue called the isthmus. Behind the thyroid are four small glands called the parathyroid glands.

The thyroid and the parathyroid glands make hormones that are important for how your body works.

How the thyroid works

The thyroid has different types of cells that make hormones to control your metabolic rate, including your heart rate, how fast you digest food, your body temperature and weight. These hormones are called T4 and T3.

There are two main types of cells in the thyroid:

- Follicular cells – These cells make and store the hormones T4 and T3, and make a protein called thyroglobulin (Tg).

- Parafollicular cells (C-cells) – These cells make the hormone calcitonin.

How common is thyroid cancer?

About 4300 people are diagnosed with thyroid cancer each year in Australia, and rates are increasing. Women are more than twice as likely to develop thyroid cancer as men.

Although it is the most common type of cancer that affects women aged 20–24, most of the people diagnosed with thyroid cancer are women in their 40s, 50s and 60s, and men in their 50s, 60s and 70s.

Learn more

What are the symptoms of thyroid cancer?

Thyroid cancer usually develops slowly, without obvious signs, but symptoms may include:

- a lump or nodule in the neck (usually painless, may grow gradually)

- swelling in the neck

- trouble swallowing

- difficulty breathing

- changes to the voice (e.g. hoarseness that doesn’t go away)

- swollen lymph nodes in the neck (may grow slowly over months or years)

- a cough that doesn’t go away.

Even though a painless lump in the neck is a typical sign of thyroid cancer, most of the time this is not a thyroid cancer. Usually, an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) or an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) is not a sign of thyroid cancer.

“People were a little dismissive because thyroid cancer has a good outlook. They said, ‘If you’re going to get cancer, that’s the best type to get’. But I didn’t find this very helpful. The word ‘cancer’ made me feel gutted and afraid.” Jenny

What are the risk factors?

The exact cause of most thyroid cancers is not known, but some things may increase your risk.

- Radiation exposure – A small number of thyroid cancers may be from radiation therapy to the head or neck as a child; living in an area with high levels of radiation; or radiation exposure at work (e.g. medical or military). Thyroid cancer usually takes 10–20 years to develop after significant radiation exposure.

- Family history – About 5% of thyroid cancers are linked to a family history. Having a parent, child or sibling with papillary thyroid cancer (see table, right), or an inherited genetic condition, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Cowden syndrome, may increase your risk. Some people inherit a faulty gene, the RET gene, that can cause familial medullary thyroid cancer (FMTC) or the thyroid condition multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN).

- Thyroid conditions – Having thyroid nodules, an enlarged thyroid (called a goitre) or inflammation of the thyroid (thyroiditis) only slightly increases your chance of developing thyroid cancer.

Having too much or too little iodine can affect your thyroid function. Whether this increases the risk of thyroid cancer is still being investigated.

The thyroid hormones

The two main hormones made in the thyroid are T4 (thyroxin) and T3 (triiodothyronine). To keep the body’s metabolism working properly, it is important that the thyroid makes the right amounts of T4 and T3.

This balance is controlled by a hormone called thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which is made in the pituitary gland, near the brain.

If levels of T4 and T3 are low, the pituitary gland makes TSH, which tells the thyroid to make more hormones. If T4 and T3 levels are too high, the pituitary gland makes less TSH.

The thyroid gland and parathyroid glands also make the hormone calcitonin, which balances calcium levels in the blood.

Your doctor may talk to you about underactive and overactive thyroid symptoms, which are explained below:

Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism)

Without enough thyroid hormone, your metabolism slows down. You may feel tired, sluggish, fatigued or depressed; gain weight; have difficulty concentrating; be constipated; and have brittle, dry hair and skin.

In severe cases, heart problems could occur.

Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism)

If you have too much thyroid hormone, your metabolism speeds up. As a result, you may lose weight and have increased appetite; feel shaky and anxious; or have rapid, strong heartbeats (palpitations).

Over time, untreated hyperthyroidism can result in loss of bone strength and problems with heart rhythm and function.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will feel your neck. If they find any swelling or a lump (called a nodule), you’ll usually have one or more of the following tests.

Common tests

Blood tests

Your thyroid hormone levels will be checked. The thyroid can still work normally with most thyroid cancers, so these levels may not be affected. If medullary thyroid cancer is suspected, calcitonin levels will also be checked.

An ultrasound

This painless scan shows the size of the thyroid, and if any nodules (lumps) are solid, cystic (full of fluid) or a mix. The nodule will usually be rated as high or low risk, and this will help decide whether a biopsy is needed.

An ultrasound can also show if nearby lymph nodes may be affected.

A biopsy

This may be done as a fine needle aspiration (FNA) during an ultrasound. The area may be numbed before a thin needle is inserted to collect a sample of cells. An ultrasound guides the needle to the right spot.

The sample is sent to a pathologist who checks it under a microscope for cancer cells. A surgical biopsy may be done if it’s unclear from other tests whether the nodule or lymph node is cancerous.

It involves surgery to remove thyroid tissue for testing (partial thyroidectomy). It can be difficult to tell if follicular tumours are cancerous from an FNA, so a surgical biopsy may be needed to check this.

Genomic tests

These blood or tissue tests look for changes (mutations) in the genes. These tests are not often needed for thyroid cancer and aren’t covered by Medicare.

You doctor may suggest these tests if they suspect medullary thyroid cancer or certain cancers that need targeted therapy. Genomic tests may show whether thyroid cancer is unlikely, which may help avoid surgery in some cases.

Imagings scans

A CT or PET-CT scan may be used to see if cancer has spread from the thyroid to other parts of the body. A full body scan is sometimes done after radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment to check if any cancer cells remain.

Staging thyroid cancer

Staging describes the size of the cancer and how far it may have spread. It may not be possible to know the stage until after surgery.

The cancer is usually classified as low, intermediate or high risk. You may be given an idea of what to expect (prognosis), based on the cancer type, how advanced it is, and if it has spread.

Treatment

Your treatment will depend on the type and stage of the cancer, and your age and general health.

Most people will have a combination of surgery, thyroid hormone replacement therapy and, sometimes, RAI treatment. Less often, people may also have targeted therapy, radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

Treatment types

Active surveillance

Some people may not need treatment right away. This is called active surveillance, and means having regular ultrasounds and check-ups.

- It is usually only for small papillary thyroid cancers that haven’t spread, or small, low-risk cancers.

- It may also be used after partial thyroidectomy surgery when only part of the thyroid remains.

- Some people choose active surveillance if treatment side effects would make them feel worse than the cancer itself.

- A specialist thyroid radiologist will need to map the tumour. If this shows that the cancer is close to muscle, the vocal nerve, windpipe or oesophagus, you will usually need to have surgery.

- Your doctor will explain changes to watch out for.

- You can usually start treatment later if you change your mind, or the cancer grows or spreads.

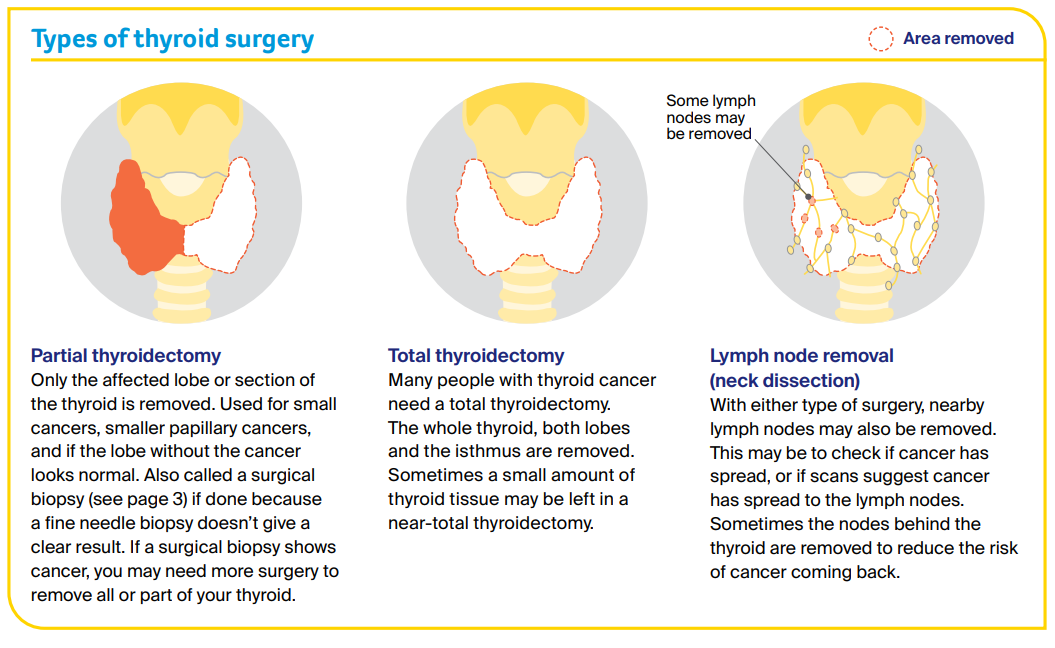

Surgery

Surgery is the most common treatment for thyroid cancer. You will be given a general anaesthetic, and the surgeon will make a cut (usually 3–5 cm) across your neck.

How much tissue and how many lymph nodes are removed will depend on how far the cancer has spread. You usually stay in hospital for 1–2 nights, but it may be a little longer.

The wound will have stitches, adhesive strips or small clips and you’ll be told how to avoid an infection. Tissue removed during surgery is tested to find the type of cancer, whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes and if you need other treatment.

More surgery is sometimes needed to remove other tissue, any remaining thyroid or the thymus gland. If the whole thyroid is removed, you will need thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Some people who have part of their thyroid removed will also need thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Depending on the type and stage of thyroid cancer, you may need RAI treatment or, in rare cases, other treatments.

Thyroid hormone replacement therapy

When the whole thyroid is removed, your body can’t make enough T4 (thyroxine) hormone. You’ll need to take tablets for the rest of your life to keep a healthy metabolism and reduce the risk of cancer returning.

This is because T4 stops your pituitary gland releasing too much TSH, which can help thyroid cancer grow. If there’s a high risk of cancer returning, you will take a high dose of T4 – called TSH suppression.

To find the right dose, you’ll have blood tests every 6–8 weeks to begin with. A small number of people experience side effects at first, including anxiety, problems sleeping, racing heart and sweating.

Tips for taking T4 medicine

- Have it at the same time every day (e.g. before breakfast or before bed).

- Take it on an empty stomach and wait 30 minutes before you eat anything.

- Wait two hours before taking other medicines or tablets, including calcium or iron supplements, as these affect the stomach’s ability to absorb the T4.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist whether your T4 medicine needs to be kept in the fridge. Some T4 medicines may need to be kept cold to maintain the T4 level in the tablets. If you are travelling, the medicine will usually last for up to 30 days out of the fridge, but check before you go.

- If you miss a dose, you should usually take it as soon as you remember, but if it’s almost time to take the next dose, skip the dose you missed.

- Check with your doctor if it’s safe to continue taking other medicines or supplements.

- Tell your doctor if you are pregnant or planning to get pregnant – you may need a higher T4 dose.

- Don’t stop taking T4 medicine without talking to your doctor first.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

EBRT is only suggested for thyroid cancer that has a high risk of coming back. It may be used if surgery hasn’t removed all the cancer near important structures such as the windpipe.

EBRT may be used for medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancers (which do not respond to RAI). Rarely, it is used as palliative treatment – to relieve symptoms if the cancer has spread.

EBRT directs high-energy radiation beams precisely to the affected area, to kill cancer cells or damage them so they cannot grow, multiply or spread.

Before treatment, the radiation therapist takes CT scans to work out the exact area to be treated and may make small marks on your skin.

This ensures the same part of your body is targeted during each treatment session. You may be fitted for a plastic mesh treatment mask, to keep you in position so radiation is given to the same area each session.

You can see and breathe through the mask, but it may feel uncomfortable, so talk to the radiation therapy team if you feel anxious. You will lie very still on a table as the machine moves around you but does not touch you.

The radiation session is painless, and you won’t feel anything. Most people have treatment weekdays for one to several weeks. However, treatment is different for everyone – so how often, and for how long you have treatment, can vary.

Treatment sessions usually take about 10 minutes, but it can take up to 30 minutes to position the machine correctly.

Feeling tired, having difficulty swallowing, having a sore throat, a dry mouth, and red, dry, itchy, sore or ulcerated skin are common side effects with EBRT for thyroid cancer.

For some people, side effects don’t happen right away – they may begin after the first few sessions. Most side effects will go away within a few weeks or months after treatment ends.

Your treatment team can help you prevent or manage any side effects if they happen.

Radioactive iodine treatment

Also called radioactive iodine ablation or thyroid ablation, this treatment destroys any remaining cancer cells and thyroid tissue left after surgery. It uses radioactive iodine (RAI) or I-131 that you take as a tablet in hospital.

RAI kills thyroid cells and thyroid cancer cells while having little effect on other body cells. You have RAI treatment weeks or months after surgery, when any swelling has gone down.

RAI is used for:

- papillary, follicular or oncocytic cancer

- cancer that has spread to lymph nodes

- cancer with a high risk of coming back

RAI is not used:

- for medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancers (which don’t take up iodine)

- if you are pregnant or breastfeeding (RAI will be done at a later time)

How to prepare for RAI treatment

Limit foods high in iodine

From two weeks before RAI treatment, avoid seafood, iodised salt, sushi, some dairy foods and certain food colourings.

Tell your doctor about recent imaging scans

Any CT or other scans using iodine dye (contrast) in the past two months can affect RAI treatment.

Raise TSH levels

For RAI treatment to work, you need to have a high level of TSH in your body. To raise TSH levels, you will usually have injections of a synthetic type of TSH hormone (called rhTSH).

You are given an rhTSH injection each day for the two days before your RAI treatment.

In rare cases, instead of injections, you may raise your TSH levels by stopping your thyroid hormone replacement medicine for 3–4 weeks.

You will need blood tests, to check that TSH levels are high enough, before you have RAI treatment. Talk to your doctor about ways to manage any hypothyroidism symptoms that develop in this period.

Your doctor will explain when to start taking your thyroid hormone replacement after RAI treatment.

RAI may have a short-term effect on eggs and sperm, so wait 6 months before trying for a baby. You need normal thyroid hormone levels before getting pregnant. Ask your doctor about fertility and RAI.

Having RAI treatment

You go to hospital the day you start treatment. After swallowing the RAI tablet, your body fluids will be radioactive for a few days, so you will need to stay in hospital for 1-3 days.

Ask your team questions before you go to hospital, so you know what to expect. Once the radiation has dropped to a safe level, you can go home.

If you had the synthetic TSH injections, this usually takes a day. A few days after treatment, you will usually have a full body scan to check for any remaining thyroid cells.

It’s normal for the scan to find some thyroid cells in the neck as small amounts of healthy thyroid tissue remain after surgery. RAI takes several months to destroy this tissue.

The scan may also show if cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other areas. Side effects are usually temporary and drinking lots of water helps the radiation pass out of your body faster, reducing your bladder’s exposure to radiation.

Some side effects, such as tiredness, are often from thyroid hormone withdrawal, and improve when your levels return to normal.

The salivary glands may absorb some iodine, leaving a dry mouth or taste and smell changes for a few weeks. You may have dry or watery eyes.

Safety precautions during RAI treatment

While in hospital you will be in a room by yourself. You may not be allowed visitors, or only short visits where people stay 2–3 metres away from you. Pack an electronic device, book or game so you’re not bored.

When you go home, you will need to take some safety measures for the first few days. These include:

- sleeping alone

- washing clothes, towels and sheets separately

- washing your hands, especially before making food

- sitting down to pee and closing the lid when you flush.

Other treatments

Most thyroid cancers respond well to common treatments, but a small number may need other options or newer treatments.

Targeted therapy

This drug treatment attacks specific features of cancer cells, to stop the cancer growing and spreading. It is given as a daily tablet, which you take for several years.

Targeted therapy may be suggested if RAI treatment isn’t working. It may also be available on clinical trials for rare or aggressive thyroid cancers.

Learn more

Chemotherapy

This may be used in combination with radiation therapy to treat anaplastic thyroid cancer or when advanced thyroid cancer has not responded to RAI treatment or targeted therapy.

Chemotherapy is given by injection into a vein (intravenously), with the number of sessions and length of treatment varying from person to person.

Learn more

Immunotherapy

This is a drug treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. It’s not commonly used for most thyroid cancers, but may be available through clinical trials for anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Learn more

Radiopeptide therapy

This radioactive nuclear medicine may be available through clinical trials for advanced medullary thyroid cancer.

A protein (peptide) combined with a small amount of radioactive substance (radionuclide) is given intravenously, through a needle into a vein. It targets cancer cells and delivers a high dose of radiation that kills or damages them.

It is also called peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).

What to expect after thyroid surgery

Voice changes

Most people feel better and return to usual activities within 1–2 weeks, but recovery may take longer. Sometimes surgery affects the nerves to the voice box, making your voice tired, hoarse or weak.

This usually improves with time, but for a small number of people some changes may be permanent.

Pain, eating and exercise

Pain medicine usually helps if you are sore from surgery. How you are positioned during surgery may give you a stiff neck or back for a while. Massage and physiotherapy may help.

For a couple of weeks, avoid heavy lifting, intense exercise like running, and turning your head quickly. It will hurt to swallow for a few days, so eat soft foods.

Your throat may feel stiff for a few months but this usually improves gradually.

Low calcium levels

If surgery affects the parathyroid glands, your blood calcium levels will be checked. Low calcium (hypocalcaemia) may cause headaches, tingling in your hands, feet and lips, and muscle cramps.

You may need vitamin D or calcium supplements until your parathyroid glands recover (or permanently). Take calcium supplements at least two hours after thyroid hormone replacement tablets.

Scarring

You will have a horizontal scar on your neck above the collarbone. This is usually about 3–5 cm long and in a natural skin crease. At first, this scar will look red, but should fade with time.

Your doctor may suggest using special tape to help the scar to heal. Keep the area moisturised and avoid sun to help the scar fade faster. Your pharmacist, doctor or nurse may suggest a suitable cream.

“I had no real side effects other than a scar, which has faded. I recovered quickly and was back at work after a couple of weeks. After the surgery, I was put on T4 (thyroxine) to get my hormones stable.” Jenny

Follow-up appointments

After your treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check the cancer hasn’t come back or spread.

During these check-ups, you may have a physical examination, blood tests, an ultrasound or other scans. You will also be able to discuss how you’re feeling and mention any concerns you may have.

Questions for your doctor

This checklist may be helpful when thinking about the questions you want to ask your doctor.

- What type of thyroid cancer do I have? Has it spread?

- Are there clinical guidelines for this type of thyroid cancer?

- What treatment do you recommend? What are the risks and possible side effects?

- If I don’t have the treatment, what can I expect?

- How long do I have to make a decision? Are there any other treatment options for me?

- How long will treatment take? Will I have to stay in hospital?

- How will we know if the treatment is working?

- Do I need to take any safety precautions after this treatment?

- Will treatment affect my fertility or my sex life?

- Can I work, drive and do my normal activities while having treatment?

- How will my thyroid hormone levels be monitored?

- Will I need to take medicine after treatment?

- How often will I need check-ups after treatment?

Thyroid cancer clinical trials

Cancer clinical trials are research studies that test whether a new approach to prevention, screening, diagnosis, or treatment works better than current methods and is safe.

There are clinical trials for thyroid cancer open to recruitment in Victoria. This list shows the most recently updated thyroid cancer studies on the Victorian Cancer Trials Link (VCTL).

Visit the VCTL to find more thyroid cancer clinical trials.