Page last updated: November 2025

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Ovarian Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2024 edition). This webpage was last updated in November 2025.

Expert content reviewers:

This information was developed based on Australian and international clinical practice guidelines, and with the help of a range of health professionals and people affected by ovarian cancer:

- Dr Antonia Jones, Gynaecological Oncologist, The Royal Women’s Hospital and Mercy Hospital for Women, VIC

- Dr George Au-Yeung, Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Centre, VIC

- Dr David Chang, Radiation Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

- Prof Anna DeFazio AM, Sydney West Chair of Translational Cancer Research, The University of Sydney, Director, Centre for Cancer Research, The Westmead Institute for Medical Research and Director, Sydney Cancer Partners, NSW

- Ian Dennis. Consumer (Carer)

- A/Prof Simon Hyde, Head of Gynaecological Oncology, Mercy Hospital for Women, VIC

- Carmel McCarthy, Consumer

- Quintina Reyes, Clinical Nurse Consultant – Gynaecological Oncology, Westmead Hospital, NSW

- Deb Roffe, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA.

Ovarian cancer starts when cells in one or both ovaries, the fallopian tubes or the peritoneum become abnormal, grow out of control and can form a lump called a tumour.

Cancer of the fallopian tube was once thought to be rare, but recent research suggests that many ovarian cancers start in the fallopian tubes.

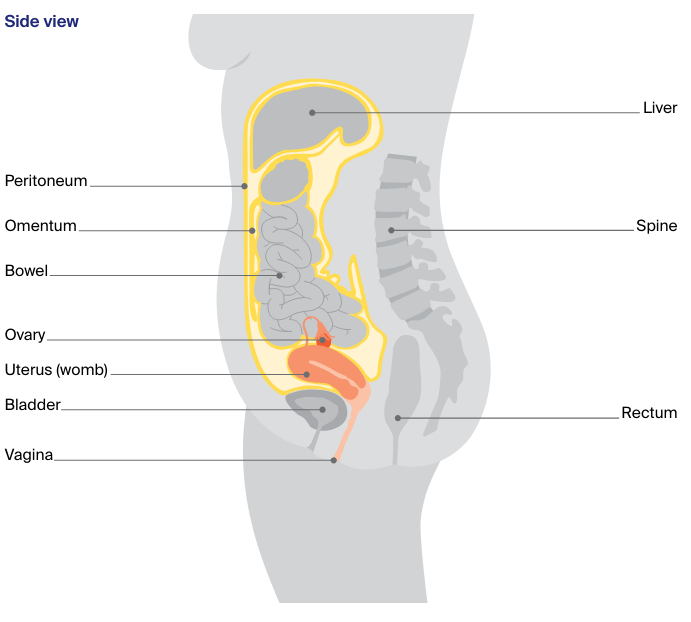

If ovarian cancer spreads from the ovaries, it is often to the organs in the abdomen and pelvis. It is common in some types of ovarian cancer for a large amount of fluid to build up in the abdomen (belly).

Sometimes an ovarian tumour is diagnosed as a borderline tumour (also known as a low malignant potential tumour). This tumour is not considered to be cancer but can still spread within the abdomen.

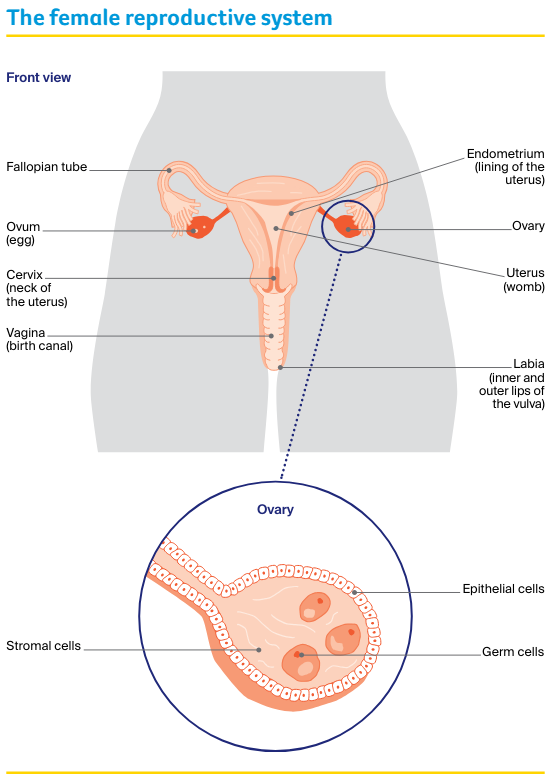

The ovaries

The ovaries are part of the female reproductive system, which also includes the fallopian tubes, uterus (womb), cervix (the neck of the uterus), vagina (birth canal) and vulva (external genitals).

The ovaries produce eggs. They also make the hormones oestrogen and progesterone, which control the release of eggs (ovulation) and the timing of periods (menstruation).

Ovaries are made up of:

- epithelial cells – found on the outside of the ovary in a layer known as the epithelium

- germ (germinal) cells – found inside the ovaries, which eventually mature into eggs (ova)

- stromal cells – form connective (supporting) tissue within the ovaries, and make the hormones oestrogen and progesterone.

The ovaries are two small, walnut-shaped organs. They are found in the lower part of the abdomen. There is one ovary on each side of the uterus, close to the end of each fallopian tube.

Other organs and structures near the ovaries include the:

- bladder – stores urine (pee)

- bowel – helps the body break down food

- rectum – stores faeces (poo)

- peritoneum – the lining of the abdomen

- omentum – the curtain of fatty tissue that hangs in front of the large bowel like an apron.

Ovulation and menstruation

During ovulation, from puberty through to menopause, one ovary – or occasionally both – releases an egg. The egg travels through the fallopian tube to the uterus.

If a pregnancy does not occur, some of the lining of the uterus is shed and flows out of the body. This flow is called a period or menstruation.

Menopause

As you get older, the ovaries gradually make less oestrogen and progesterone. When levels of these hormones fall low enough, periods stop. This is known as menopause. After menopause, you can’t have a child naturally.

Your guide to best cancer care

A lot can happen in a hurry when you’re diagnosed with cancer. The guide to best cancer care for ovarian cancer can help you make sense of what should happen.

It will help you with what questions to ask your health professionals to make sure you receive the best care at every step.

Read the guide

Types of ovarian cancer

There are many types of ovarian cancer. The three main types start in different cells found in the ovary.

Epithelial

- the most common type of ovarian cancer (about 90% of cases)

- starts on the surface layer (epithelium) of the ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum

- the most common subtypes include serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous

- serous is the most common subtype; it’s divided into high grade and low grade

- mostly occurs over the age of 60

Stromal cell (or sex cord-stromal tumours)

- rare cancer (about 10% of cases)

- starts in the cells that form the connective tissue in the ovaries and make the hormones oestrogen and progesterone

- may produce extra hormones, such as oestrogen

- usually occurs between the ages of 40 and 60

Germ cell

- rare type of ovarian cancer (less than 10% of cases)

- starts in the egg-producing (germinal) cells found inside the ovary

- usually occurs under the age of 40.

Non-cancerous ovarian tumour

- also known as a borderline tumour

- abnormal cells that form in the tissue covering the ovary

- doesn’t grow into the supportive tissue (stroma)

- grows slowly

How common is ovarian cancer?

Each year, about 1785 Australians are diagnosed with ovarian cancer – this includes cancers of the fallopian tube. Over 80% of people diagnosed are over the age of 50, but ovarian cancer can occur at any age.

It is the ninth most common cancer in females in Australia.

Ovarian cancer mostly affects women, but anyone with ovaries can get it. Transgender men and intersex people can also get ovarian cancer if they have ovaries. For information specific to you, speak to your doctor.

More on ovarian cancer statistics and trends

Symptoms

The symptoms of ovarian cancer can be similar to other common conditions. This can make it difficult to diagnose early. Symptoms are more likely to develop as the cancer grows.

Symptoms for ovarian cancer include:

- pressure, pain or discomfort in the abdomen or pelvis

- a swollen or bloated abdomen

- appetite changes (e.g. not feeling like eating, feeling full quickly)

- changes in toilet habits (e.g. constipation, diarrhoea, passing urine more often, increased wind)

- indigestion and feeling sick (nausea)

- feeling very tired

- unexplained weight loss or weight gain

- changes to periods such as heavy or irregular bleeding, or vaginal bleeding after menopause

- pain when having sex.

If you have any of these symptoms and they are new for you, are severe or continue for more than two to three weeks, it is best to have a check-up.

Keep a note of how often the symptoms occur and make an appointment to see your general practitioner (GP).

Ovarian Cancer Australia has produced a diary for recording symptoms. You can also use it to help talk about your health concerns with your doctor.

Contact cancer support

Call our cancer information and support line on 13 11 20 to talk to a cancer nurse and get the support you need.

It's available to anyone affected by cancer – those diagnosed, family, friends, and carers. Monday to Friday, 9am-5pm.

Get support

Risk factors

The causes of ovarian cancer are largely unknown, but factors that can increase the risk of developing ovarian cancer include:

- age – ovarian cancer is most common in women over 50 after periods have stopped, and the risk increases with age.

- genetic factors – up to 20% of serous ovarian cancers (the most common subtype) are linked to an inherited faulty gene, and a smaller proportion of other types are also related to genetic faults.

- family history – having close blood relatives (e.g. mother, sister) diagnosed with ovarian, uterine, breast or bowel cancers, or having Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.

- endometriosis – this condition is caused by tissue from the lining of the uterus growing outside the uterus.

- reproductive history – women who have not had children, who have had assisted reproduction (e.g. in-vitro fertilisation or IVF), or who have had children after the age of 35 may be slightly more at risk.

- lifestyle factors – some types of ovarian cancer have been linked to smoking or carrying extra weight.

- hormonal factors – for example, early puberty or late menopause. Some studies suggest that menopause hormone therapy (MHT), previously called hormone replacement therapy (HRT), may increase the risk of ovarian cancer if taken for five years or more, but the risk is very low.

Some factors reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer. These include having children before the age of 35, breastfeeding, using the combined oral contraceptive pill for several years, and having your fallopian tubes tied (tubal ligation) or removed.

Does ovarian cancer run in families?

Ovarian cancer most often occurs for unknown reasons but some cases are due to an inherited faulty gene.

Having an inherited faulty gene does not mean you will definitely develop ovarian cancer, and you can inherit a faulty gene without having a history of cancer in your family.

About 15% of women with ovarian cancer have an inherited fault in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes or other similar genes. This can also increase the risk of developing breast cancer and fallopian tube cancer.

Less commonly, a group of gene faults known as Lynch syndrome is associated with ovarian cancer and can also increase the risk of developing cancer of the bowel or uterus.

As other genetic conditions are discovered, they may be included in genetic tests for cancer risk.

More on family history and cancer

Health professionals

Your GP will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist called a gynaecological oncologist. The specialist will arrange further tests.

If ovarian cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care, including a gynaecological pathologist, radiologist, genetic counsellor and social worker, among others.

Question checklist

Asking your doctor questions will help you make an informed choice. You may want to include some of these questions in your own list.

Diagnosis

- What type of ovarian cancer do I have?

- Has the cancer spread? If so, where has it spread? How fast is it growing?

- Are the latest tests and treatments for this cancer available in this hospital?

- What sort of genetic testing can I have? Can I see a genetic counsellor?

- Will a multidisciplinary team be involved in my care?

- Are there clinical guidelines for this type of cancer?

Treatment

- What treatment do you recommend? What is the aim of the treatment?

- Are there other treatment choices for me? If not, why not?

- If I don’t have the treatment, what should I expect?

- How long do I have to make a decision?

- I’m thinking of getting a second opinion. Can you recommend anyone?

- How long will treatment take? Will I have to stay in hospital?

- Are there any out-of-pocket expenses not covered by Medicare or my private health cover? Can the cost be reduced if I can’t afford it?

- How will we know if the treatment is working?

- Are there any clinical trials or research studies I could join?

Side effects

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment?

- Will I have a lot of pain? What will be done about this?

- Can I work, drive and do my normal activities while having treatment?

- Will the treatment affect my sex life and fertility? What are my options?

- Should I change my diet or physical activity during or after treatment?

- Are there any complementary therapies that might help me?

After treatment

- How often will I need check-ups after treatment? Who should I see?

- If the cancer returns, how will I know? What treatments could I have?