Page last updated: November 2025

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Breast Cancer - Information for people affected by cancer (2024 edition). This webpage was last updated in November 2025.

Expert content reviewers:

This information is based on Australian clinical practice guidelines for early breast cancer and international guidelines for advanced breast cancer. It was developed with the help of a range of health professionals and people affected by breast cancer:

- Dr Diana Adams, Medical Oncologist, Macarthur Cancer Therapy Centre, NSW

- Prof Bruce Mann, Specialist Breast Surgeon and Director, Breast Cancer Services, The Royal Melbourne and The Royal Women’s Hospitals, VIC

- Dr Shagun Aggarwal, Specialist Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, Prince of Wales, Sydney Children’s and Royal Hospital for Women, NSW

- Andrea Concannon, consumer

- Jenny Gilchrist, Nurse Practitioner Breast Oncology, Macquarie University Hospital, NSW

- Monica Graham, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA

- Natasha Keir, Nurse Practitioner Breast Oncology, GenesisCare, QLD

- Dr Bronwyn Kennedy, Breast Physician, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse and Westmead Breast Cancer Institute, NSW

- Lisa Montgomery, consumer

- A/Prof Sanjay Warrier, Specialist Breast Surgeon, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW

- Dr Janice Yeh, Radiation Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC

What is breast cancer?

Breast cancer is the abnormal growth of cells in the breast. It usually starts in the lining of the breast ducts or lobules, and can grow into cancerous (malignant) tumours.

Most breast cancers are found when they are invasive. This means that the cancer has spread from the breast ducts or lobules into the surrounding breast tissue.

Invasive breast cancer can be early, locally advanced or advanced (metastatic). Advanced breast cancer is when cancer cells have spread (metastasised) outside the breast and nearby lymph nodes to other parts of the body.

About 5% of cancers are advanced when breast cancer is first diagnosed.

This information has been prepared to help you understand more about early and locally advanced breast cancer, and includes a short section on advanced (metastatic) breast cancer.

The breasts

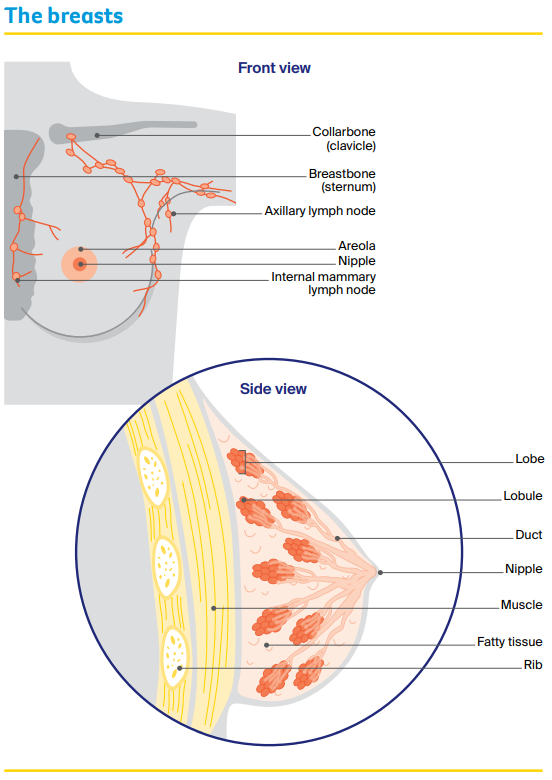

The breasts sit on top of the upper ribs and a large chest muscle. They cover the area from the collarbone (clavicle) to the armpit (axilla) and across to the breastbone (sternum).

Some breast tissue extends into the armpit and is called the axillary tail. Female breasts are mostly made up of:

- lobes – each breast has 12–20 sections called lobes.

- lobules – each lobe contains glands that can produce milk. These milk glands are called lobules or glandular tissue.

- ducts – the lobes and lobules are connected by fine tubes called ducts. The ducts carry milk to the nipples when breastfeeding.

- fatty/fibrous tissue – all breasts contain some fatty or fibrous tissue (including connecting tissue called stroma), no matter what their size.

Most younger women have dense or thicker breasts, because they contain more lobules than fat. Male breasts have ducts and fatty/fibrous tissue. They contain no, or only a few, lobes and lobules.

The lymphatic system

The lymphatic system is an important part of the immune system, which protects against disease and infection. The lymphatic system drains excess fluid from body tissues into the blood.

It is made up of a network of thin tubes called lymph vessels. These vessels connect to groups of small, bean-shaped lymph nodes (or glands).

There are lymph nodes throughout the body, including in the armpits, neck, abdomen, groin and chest (near the breastbone).

The first place breast cancer cells usually spread to is the lymph nodes in the armpits (axillary lymph nodes) or to the lymph nodes near the breastbone (internal mammary lymph nodes).

Your guide to best cancer care

A lot can happen in a hurry when you’re diagnosed with cancer. The guide to best cancer care for breast cancer can help you make sense of what should happen.

It will help you with what questions to ask your health professionals to make sure you receive the best care at every step.

Read the guide

Types of breast conditions

Non-invasive breast conditions

These are conditions where the abnormal cells have not invaded nearby tissues. Also called carcinoma in situ.

- Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) – abnormal cells in the ducts of the breast, which may develop into invasive breast cancer. Treatment is the same as invasive breast cancer, but chemotherapy is not used.

- Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) – abnormal cells in the breast lobules, which does not develop into cancer but increases risk of developing cancer including in the other breast. LCIS is usually treated with surgery, and hormone therapy may be used. More regular mammograms or other scans needed to check for any changes.

Invasive breast conditions

Invasive means that the cancer cells have grown and spread beyond the breast ducts/lobules and into the surrounding tissue.

The two main types of invasive breast cancer are named after the breast area that they start in:

- Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) – starts in the breast ducts. About 80% of breast cancers are IDC.

- Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) – starts in the breast lobules. About 10% of breast cancers are ILC.

Less common breast cancers include inflammatory breast cancer, medullary carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, Paget disease of the nipple (or breast) and papillary carcinoma.

Phyllodes tumour is a rare breast condition that may be benign or malignant.

If invasive breast cancer spreads beyond the breast tissue and the nearby lymph nodes it is called advanced or metastatic breast cancer. For more information, call us on 13 11 20 or visit Breast Cancer Network Australia.

How common is breast cancer?

There are about 20,000 people diagnosed with breast cancer in Australia every year.

Women

In Australia, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women (apart from common skin cancers), with one in eight women diagnosed by age 85.

Young women can get breast cancer, but it is more common over the age of 40, and the risk increases with age. In rare cases, pregnant or breastfeeding women can get breast cancer.

See a doctor about any persistent lump noticed during pregnancy.

Men

About 220 men (most aged over 60) are diagnosed with breast cancer each year. It is treated in the same way as for women.

For more information, visit Cancer Australia or Breast Cancer Network Australia.

Transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse people

Any transgender woman taking medicines to boost female hormones and lower male hormones has a higher breast cancer risk (compared with a man).

A transgender man who has had breasts removed in a nipple-sparing mastectomy can still get breast cancer, although the risk is low.

See LGBTQI+ People and Cancer for more information.

Learn more

Risk factors

Many factors can increase your risk of breast cancer, but they do not mean that you will definitely develop it. You can also have none of the known risk factors and still get breast cancer. If you are worried, speak to your doctor.

Personal factors

- Being female is the biggest risk factor – 99% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed in women.

- Risk increases with age for both men and women.

- About three quarters of breast cancer cases are in women over the age of 50. Free breast screening is available.

- Dense breast tissue (as seen on a mammogram) increases your risk.

- Breast implants do not increase breast cancer risk, but some implants are linked with a type of cancer called lumphome. See the Therapeutic Goods Administration website for more information.

Lifestyle factors

- Being overweight or gaining weight after menopause. Losing weight to a healthy range can lower this.

- Drinking alcohol – the more that you drink, the higher your risk. If you choose to drink, the alcohol guidelines suggest you drink no more than 10 standard drinks a week, and no more than four standard drinks on any one day.

- Not getting enough exercise or not being physically active.

- Smoking tobacco.

Family history

- About 5–10% of breast cancers are due to an inherited breast cancer gene such as BRCA1 or BRCA2.

- Most people with breast cancer do not have a strong family history. However, having several close relatives (e.g. mother, sister, aunt) on the same side of the family who have had breast or ovarian cancer may increase your risk.

- Several close relatives on the same side of the family with prostate or pancreatic cancer may increase your risk.

Hormonal factors

- Long-term use of menopause hormone therapy (MHT) containing both oestrogen and progesterone.

- Taking the oral contraceptive pill (the pill) for a long time may slightly increase the risk.

- You or your mother using diethylstilboestrol (DES) during pregnancy.

- Transgender women taking gender-affirming hormones for more than five years.

Medical history

- Having been previously diagnosed with breast cancer, LCIS or DCIS.

- Some non-cancerous conditions of excessive growth of breast cells (atypical ductal hyperplasia or ADH).

- Having radiation therapy to the chest area for Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Males with a rare genetic syndrome called Klinefelter syndrome. Those with this syndrome have three sex chromosomes (XXY) instead of the usual two (XY).

Reproductive factors

- Never having given birth to a child.

- Starting your first period (menstruating) before the age of 12.

- Being older than age 30 when you gave birth to your first child .

- Never having breastfed a child.

- Going through menopause after the age of 55.

Does breast cancer run in families?

Most people with breast cancer don’t have a family history, but a small number may have inherited a gene fault (also called a mutation) that increases their breast cancer risk.

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 – these are the most common gene mutations linked to breast cancer. Women in families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 are at increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers. Men in families with BRCA2 may be at increased risk of breast and prostate cancers.

- Other genes linked to breast cancer – these include ATM, BARD1, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, and TP53. More gene mutations linked to breast cancer are being found all the time. A genetic test called an extended gene panel test checks for the most common types of genes linked with breast cancer.

To find out if you have inherited a gene mutation, talk to your doctor or breast cancer nurse about visiting a family cancer clinic or genetic oncologist. Your specialist may also be able to order genetic tests.

In particular, women diagnosed before 40 years, those with triple negative breast cancer diagnosed before 60 years, and men with breast cancer should ask for a referral.

Genetic testing is covered by Medicare for some, but not all, people; ask your doctor about this.

Learn more

Symptoms

Breast cancer sometimes has no symptoms, so regular checks are important for women aged 40 and over. Breast changes may not mean cancer, but see a doctor if you notice:

- a lump, lumpiness or thickening, especially in just one breast

- a change in the size or shape of the breast or swelling

- a change to the nipple – change in shape, crusting, sores or ulcers, redness, pain, a clear or bloody discharge, or a nipple that turns in (inverted nipple) when it used to stick out

- a change in the skin – dimpling or indentation, a rash or itchiness, scaly appearance, unusual redness or other colour changes

- swelling or discomfort in the armpit or near the collarbone

- ongoing, unusual breast pain not related to your period.

Health professionals

You may be sent for tests after a screening mammogram, or your general practitioner (GP) may arrange tests to check your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist or breast clinic.

If breast cancer is diagnosed, you will see a breast surgeon or a medical oncologist, who will talk to you about your treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care. You may not see all members of the MDT.

Question checklist

Asking your doctor questions will help you make an informed choice. You may want to include some of these questions in your own list.

Diagnosis

- What type of breast cancer do I have?

- Has the cancer spread? If so, where has it spread? How fast is it growing?

- Are the latest tests/treatments for this cancer available in this hospital?

- Will a multidisciplinary team be involved in my care?

- Are there clinical guidelines for this type of cancer?

Treatment

- What treatment do you recommend? What is the aim of the treatment?

- Are there other treatment choices for me? If not, why not?

- If I don’t have the treatment, what should I expect?

- How long do I have to make a decision?

- I’m thinking of getting a second opinion. Can you recommend anyone?

- How long will treatment take? Will I have to stay in hospital?

- Are there any out-of-pocket expenses not covered by Medicare or my private health cover? Can the cost be reduced if I can’t afford it?

- How will we know if the treatment is working?

- Are there any clinical trials or research studies I could join?

Side effects

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment?

- Will I have a lot of pain? What will be done about this?

- Can I work, drive and do my normal activities while having treatment?

- Will the treatment affect my sex life and fertility?

- Should I change my diet or physical activity during or after treatment?

- Are there any complementary therapies that might help me?

After treatment

- How often will I need check-ups after treatment?

- If the cancer returns, how will I know? What treatments could I have?