Making treatment decisions

Sometimes it is difficult to decide on the type of treatment to have. You may feel that everything is happening too fast, or you might be anxious to get started. Check with your specialist how soon treatment should begin, as it may not affect the success of the treatment to wait a while. Ask them to explain the options, and take as much time as you can before making a decision.

- Know your options – Understanding the disease, the available treatments, possible side effects and any extra costs can help you weigh up the options and make a well-informed decision. Check if the specialist is part of a multidisciplinary team and if the treatment centre is the most appropriate one for you – you may be able to have treatment closer to home, or it might be worth travelling to a centre that specialises in a particular treatment.

- Record the details – When your doctor first says you have cancer, you may not remember everything you are told. Taking notes can help. If you would like to record the discussion, ask your doctor first. It is a good idea to have a family member or friend go with you to appointments to join in the discussion, write notes or simply listen.

- Ask questions – If you are confused or want to check anything, it is important to ask your specialist questions. Try to prepare a list before appointments. If you have a lot of questions, you could talk to a cancer care coordinator or nurse.

- Consider a second opinion – You may want to get a second opinion from another specialist to confirm or clarify your specialist’s recommendations or reassure you that you have explored all of your options. Specialists are used to people doing this. Your GP or specialist can refer you to another specialist and send your initial results to that person. You can get a second opinion even if you have started treatment or still want to be treated by your first doctor. You might decide you would prefer to be treated by the second specialist.

- It’s your decision – Adults have the right to accept or refuse any treatment that they are offered. For example, some people with advanced cancer choose treatment that has significant side effects even if it gives only a small benefit for a short period of time. Others decide to focus their treatment on quality of life. You may want to discuss your decision with the treatment team, GP, family and friends.

See Cancer care and your rights for more information.

Clinical trials

Your doctor or nurse may suggest you take part in a clinical trial. Doctors run clinical trials to test new or modified treatments and ways of diagnosing disease to see if they are better than current methods.

Over the years, trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer. If you decide to take part in a clinical trial, you can withdraw at any time.

Learn more

Cancer of the uterus is often diagnosed early, before it has spread. In many cases, surgery will be the only treatment needed. If cancer has spread beyond the uterus, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or hormone therapy may also be used.

Surgery

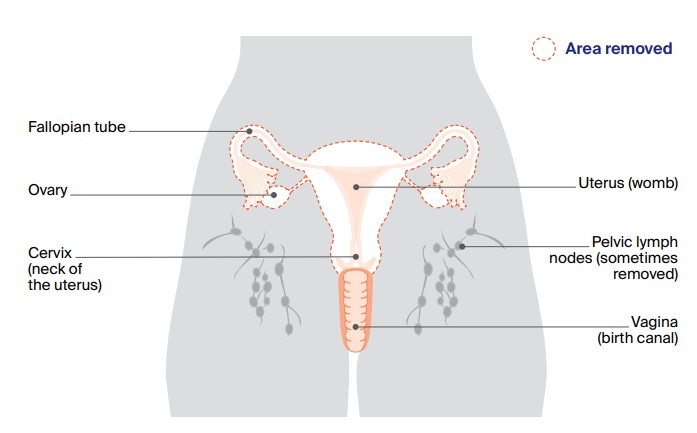

Cancer of the uterus is usually treated with an operation that removes the uterus and cervix (total hysterectomy), along with both fallopian tubes and ovaries (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy).

If your ovaries appear normal, you don’t have any risk factors, and it is an early-stage, low-grade cancer, you may be able to keep your ovaries. If the cancer has spread beyond the cervix, the surgeon may also remove a small part of the upper vagina and the ligaments supporting the cervix.

The hysterectomy can be done in different ways, depending on a number of factors, such as your age and build, the size of your uterus, the tumour size, and the surgeon’s specialty and experience.

- Keyhole surgery (laparoscopic hysterectomy) – A surgeon inserts a laparoscope (a thin tube with a light and camera) and instruments through about four small cuts in the abdomen (belly). The uterus and other organs are removed through the vagina.

- Robotic-assisted hysterectomy – This is a special form of keyhole surgery. The instruments and camera are inserted through four small cuts and controlled by robotic arms guided by the surgeon, who sits next to the operating table.

- Open surgery (abdominal hysterectomy or laparotomy) – The surgery is performed through the abdomen. A cut is usually made from the pubic area to the belly button. The uterus and other organs are then removed.

Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Most people with cancer of the uterus will have this operation, which removes the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries (as shown by the dotted line). Sometimes one or more pelvic lymph nodes are also removed to help with staging.

A pathologist examines all removed tissue and fluids. The results will help confirm the type of cancer of the uterus, if it has spread (metastasised), and its stage and grade. The cancer may also be tested for particular gene changes.

The surgery will be performed under a general anaesthetic. Your surgeon will discuss the most appropriate surgery for you, and explain the risks and benefits.

The type of hysterectomy you have depends on a number of factors, such as: your age and build; the size of your uterus; the tumour size; and the surgeon’s specialty and experience.

What to expect after surgery

When you wake up after the operation, you will be in a recovery room near the operating theatre. Once you are fully conscious, you will be transferred to the ward.

- Tubes and drips – You will have an intravenous drip in your arm to give you medicines and fluid, and a tube (catheter) in your bladder to collect urine (wee). These will usually be removed the day after the operation.

- Length of stay – You will stay in hospital for about 1–4 days. How long you stay will depend on the type of surgery you had and how quickly you recover. Most people who have keyhole surgery will be able to go home on the first or second day after the surgery (and occasionally on the day of surgery).

- Pain – As with all major surgery, you will have some discomfort or pain. The level of pain will depend on the type of operation. After keyhole surgery, you will usually be given pain medicine to swallow. If you have open surgery, you may be given pain medicine in different ways such as through a drip into a vein (intravenously), via a local anaesthetic injection into the abdomen (a transverse abdominis plane or TAP block), via a local anaesthetic injection into your back, with a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system, a machine that allows you to press a button for a measured dose of pain relief.

While you are in hospital, let your doctor or nurse know if you are in pain so they can adjust your medicines to make you as comfortable as possible. Do not wait until the pain is severe. After you go home, you can continue taking pain medicine as needed.

- Wound care – You can expect some light vaginal bleeding after the surgery, which should stop within 2 weeks. Your treatment team will talk to you about how you can keep the wound/s clean to prevent infection once you go home.

- Blood clot prevention – You will be given a daily injection of a blood thinner to reduce the risk of blood clots. Depending on your risk of clotting, you may be taught to give this injection to yourself so you can continue it for a few weeks at home. You may also be advised to wear compression stockings for up to four weeks to help the blood in your legs circulate well and prevent clots.

- Constipation – The medicines used during and after surgery can cause constipation (difficulty having bowel movements). Talk to your treatment team about how to manage this – they may suggest medicines to help prevent or relieve constipation. Once your surgeon says you can get out of bed, walking around can also help.

- Test results – Your doctor will have all the test results about a week after the operation. Whether more treatment is necessary will depend on the type, stage and grade of the disease, and the amount of remaining cancer, if any. If the cancer is at a very early stage, you may not need further treatment.

Taking care of yourself at home after a hysterectomy

Your recovery time will depend on the type of surgery you had, your age and general health. In most cases, you will feel better within 1–2 weeks and should be able to fully return to your usual activities after 4–8 weeks.

If you don’t have support from family, friends or neighbours, ask your nurse or a social worker at the hospital whether it is possible to get help at home while you recover.

- Rest up – When you get home from hospital, you will need to take things easy for the first week.

- Nutrition – To help your body recover from surgery, eat a well-balanced diet that includes a variety of foods. Include proteins such as lean meat, fish, eggs, milk, yoghurt, nuts, and legumes/beans

- Work – You will probably need 4–6 weeks of leave from work, depending on the type of surgery and nature of your job. People who have had keyhole surgery and have office jobs that don’t require heavy lifting can often return to work after 2–4 weeks.

- Driving – You will need to avoid driving after the surgery until you are able to move freely without pain.

- Lifting – You may be advised to avoid heavy lifting (more than 3–4 kg) for 4–6 weeks. This will depend on the way the surgery was done.

- Bowel problems – It is important to avoid straining during bowel movements (pooing).

- Bathing – Your doctor may advise taking showers instead of baths for 4–5 weeks after surgery.

- Exercise – Your treatment team will probably encourage you to walk the day of the surgery. Exercise has been shown to help people manage some treatment side effects and speed up a return to usual activities. To avoid infection, it’s best to avoid swimming for 4–5 weeks after surgery.

- Sex – Sexual intercourse should be avoided for about 8–12 weeks after surgery. Ask your doctor or nurse when you can have sex again, and explore other ways you and your partner can be intimate, such as massage.

Side effects after surgery

You may experience some side effects and changes from surgery, including:

- Menopause – If your ovaries are removed and you have not been through menopause, removal will cause sudden menopause.

- Impact on sexuality – The changes you experience after surgery may affect how you feel about sex and how you respond sexually. You may notice changes such as vaginal dryness and loss of libido.

- Lymphoedema – The removal of lymph nodes from the pelvis can stop lymph fluid from draining normally, causing swelling in the legs (or sometimes the vulva) known as lymphoedema. The risk of developing lymphoedema is low following most operations for cancer of the uterus, but it is higher in women who had a full lymphadenectomy, followed by external beam radiation therapy.

- Vaginal vault prolapse – This is when the top of the vagina drops towards the vaginal opening because the structures that support it have weakened. To help prevent prolapse, it is important to do pelvic floor exercises several times a day.

Treatment of lymph nodes

Cancer cells can spread from the uterus to the pelvic lymph nodes. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, you may have additional treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Lymph nodes can be checked in two ways:

Lymphadenectomy (lymph node dissection) – For more advanced or higher-grade tumours, the surgeon may remove some lymph nodes from the pelvic area to see if the cancer has spread beyond the uterus.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy – This test helps to identify the pelvic lymph node that the cancer is most likely to spread to first (the sentinel node). Your doctor will inject a dye into the cervix that flows to the sentinel lymph node, which will be removed for testing.

Radiation therapy

For cancer of the uterus, radiation therapy is commonly used as an additional treatment after surgery to reduce the chance of the disease coming back. This is called adjuvant therapy. In some cases, radiation therapy may be recommended as the main treatment if other health conditions mean you are not well enough for a major operation.

There are two main ways of delivering radiation therapy – internally or externally. Some people are treated with both types of radiation therapy.

Internal radiation therapy (brachytherapy)

Internal radiation therapy may be used after a hysterectomy to deliver radiation directly to the top of the vagina (vaginal vault) from inside your body. This is known as vaginal vault brachytherapy.

During each treatment session, a plastic cylinder (the applicator) is inserted into the vagina. The applicator is connected by plastic tubes to a machine that contains a small, radioactive seed (made of metal). Next, this seed moves from the machine into the applicator where it delivers a targeted dose of radiation to the area affected by cancer. After a few minutes, the seed is returned to the machine. The applicator is taken out of the vagina after each session.

This type of brachytherapy does not need any anaesthetic and each treatment session usually takes only 20–30 minutes. You are likely to have 3–6 treatment sessions as an outpatient over 1–2 weeks.

If you are having radiation therapy as the main treatment and haven’t had a hysterectomy, the internal radiation therapy may involve placing an applicator inside the uterus. This is done under anaesthetic or sedation, and may require a short hospital stay

External beam radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) directs the radiation at the cancer and surrounding tissue from outside the body. For cancer of the uterus, the lower abdominal area and pelvis are treated, but if the cancer has spread (metastasised), other areas may also be treated.

Planning for EBRT may involve a number of visits to your doctor to have more tests, such as blood tests and scans. Each EBRT session lasts about 30 minutes, with the treatment itself taking only a few minutes.

You will lie on a treatment table under a large machine known as a linear accelerator, which delivers the radiation. The treatment is painless (like having an x-ray), but may cause side effects. You will probably have EBRT as daily treatments, Monday to Friday, for 5–6 weeks as an outpatient. It’s very important that you attend all of your scheduled sessions to ensure you receive enough radiation to make the treatment effective.

Side effects of radiation therapy

The side effects you experience will vary depending on the type and dose of radiation, and the areas treated. Brachytherapy tends to have fewer side effects than EBRT. Side effects often get worse during treatment and just after the course of treatment has ended. They usually get better within weeks, through some may continue for longer. Some side effects may not show up until many months or years after treatment, and these are called late effects.

Short-term side effects can include:

- fatigue

- bowel and bladder problems

- nausea and vomiting

- vaginal discharge

- skin redness, soreness and swelling.

Long-term or late effects can include:

How cancer treatment affects fertility

If you have not yet been through menopause, having a hysterectomy or radiation therapy for cancer of the uterus will mean you won’t be able to become pregnant.

A small number of women with early-stage, low-grade uterine cancer choose to wait until after they have had children to have a hysterectomy. These women may be offered hormone therapy and carefully monitored while waiting to have surgery.

Learn more about fertility and cancer

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells. Chemotherapy may be used:

- for certain types of cancer of the uterus that are more aggressive

- when cancer comes back after surgery or radiation therapy to try to control the cancer and to relieve symptoms

- if the cancer does not respond to hormone therapy

- if the cancer has spread beyond the pelvis when first diagnosed

- during radiation therapy (chemoradiation) or after radiation therapy.

Chemotherapy is usually given by injecting the drugs into a vein (intravenously). You may be treated as an outpatient or, very rarely, you may need to stay in hospital overnight. You will have a number of treatments, sometimes up to six, every 3–4 weeks over several months.

Side effects of chemotherapy

The side effects of chemotherapy vary greatly and depend on the drugs you receive, how often you have the treatment, and your general fitness and health. Side effects may include feeling sick, vomiting, fatigue, hair loss, ringing or buzzing in the ears (tinnitus) and numbness and tingling in the hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy). Most side effects are temporary and steps can often be taken to prevent or reduce their severity.

Chemoradiation

High-risk endometrial cancer is often treated with EBRT in combination with chemotherapy to reduce the chance of the cancer coming back after treatment is over. When radiation therapy is combined with chemotherapy, it is known as chemoradiation. The chemotherapy drugs make the cancer cells more sensitive to radiation therapy.

If you have chemoradiation, you will usually receive chemotherapy once a week a few hours before some radiation therapy sessions. Once the radiation therapy is over, you may have another 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy on its own.

Side effects of chemoradiation include fatigue, diarrhoea, needing to pass urine more often or in a hurry, cystitis, dry and itchy skin in the treatment area, numbness and tingling in the hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy), ringing or buzzing in the ears (tinnitus)and low blood counts. Low numbers of blood cells may cause anaemia, infections or bleeding problems.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy may also be called endocrine therapy or hormone blocking therapy. Hormones such as oestrogen and progesterone are substances that are produced naturally in the body. They help control the growth and activity of cells. Some cancers of the uterus depend on oestrogen or progesterone to grow. These are known as hormone-dependent or hormone-sensitive cancers and can sometimes be treated with hormone therapy.

Hormone therapy may be recommended for uterine cancer that has spread or come back (recurred), particularly if it is a low-grade cancer. It is also sometimes offered as the first treatment if surgery has not been done (e.g. when a woman with early-stage, low-grade uterine cancer chooses not to have a hysterectomy because she wants to have children, or if a person is too unwell for surgery).

The main hormone therapy for hormone-dependent cancer of the uterus is progesterone that has been produced in a laboratory. High-dose progesterone is available in tablet form (usually medroxyprogesterone) or through a hormone-releasing intrauterine device (IUD) called a Mirena, which is placed into the uterus by your doctor.

Side effects of hormone therapy

The common side effects of progesterone treatment include breast tenderness, headaches, tiredness, nausea, menstrual changes and bloating. In high doses, progesterone may increase appetite and cause weight gain. If you have an IUD, it may move out of place and need to be refitted by your doctor.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a type of drug treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

An immunotherapy drug called pembrolizumab (used in combination with the targeted therapy drug lenvatinib, see below) may be an option for some people with endometrial cancer that has spread (metastatic disease) or is no longer responding to treatment with chemotherapy.

Side effects of immunotherapy

Common side effects include: fatigue; being or feeling sick (nausea); skin rash and itching; joint pain; diarrhoea; dry eyes; and joint pain.

Rarely, immunotherapy can affect the lungs, bowel or thyroid gland and these side effects can sometimes be life-threatening.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a drug treatment that attacks specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading.

A targeted therapy drug called lenvatinib may be used to treat endometrial cancer that has spread or come back, or to boost the effectiveness of immunotherapy

Side effects of targeted therapy

Common side effects include: fatigue; being or feeling sick (nausea); diarrhoea; constipation; sore mouth; blood pressure changes; appetite loss; bleeding and bruising; skin problems; joint aches; and headache. Less common side effects, such as heart problems and stroke, can also occur.

Palliative treatment

Palliative treatment helps to improve people’s quality of life by managing symptoms of cancer without trying to cure the disease. Many people think that palliative treatment is for people at the end of their life, but it can help at any stage of advanced cancer of the uterus. It is about living as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can.

As well as slowing the spread of cancer, palliative treatment can relieve any pain and help manage other symptoms. It is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, social and spiritual needs. The team also supports families and carers.

Understanding Cancer of the Uterus

Download our Understanding Cancer of the Uterus booklet to learn more and find support

Download now Order for free

Expert content reviewers:

A/Prof Orla McNally, Consultant Gynaecological Oncologist, Director Oncology/Dysplasia, Royal Women’s Hospital, Honorary Clinical Associate Professor, University of Melbourne, and Director of Gynaecology Tumour Stream, Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre, VIC; A/Prof Yoland Antill, Medical Oncologist, Peninsula Health, Parkville Familial Cancer Centre, Cabrini Health and Monash University, VIC; Grace Guerzoni, Consumer; Zeina Hayes, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council Victoria; Bronwyn Jennings, Gynaecology Oncology Clinical Nurse Consultant, Mater Hospital Brisbane, QLD; A/Prof Christopher Milross, Director of Mission and Radiation Oncologist, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; Mariad O’Gorman, Clinical Psychologist, Liverpool Cancer Therapy Centre and Bankstown Cancer Centre, NSW

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Cancer of the Uterus - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2023 edition). This webpage was last updated in November 2023.