What is testicular cancer?

Cancer that develops in the cells of a testicle is called testicular cancer or cancer of the testis (plural: testes). Usually only one testicle is affected, but in some cases both are affected.

As testicular cancer grows, it can spread to lymph nodes in the abdomen or to other parts of the body, such as the bones, lungs or liver. About 90 to 95 per cent of testicular cancers start in the cells that develop into sperm, which are known as germ cell tumours. Rarely, germ cell tumours can grow in other parts of the body, such as the brain, middle of the chest and back of the abdomen. These tumours are called extragonadal germ cell tumours, and are treated in a similar way to testicular cancer.

Anyone with a testicle can get testicular cancer, including transgender women, non-binary people or intersex people. For more information, see LGBTQI+ People and Cancer.

The testicles

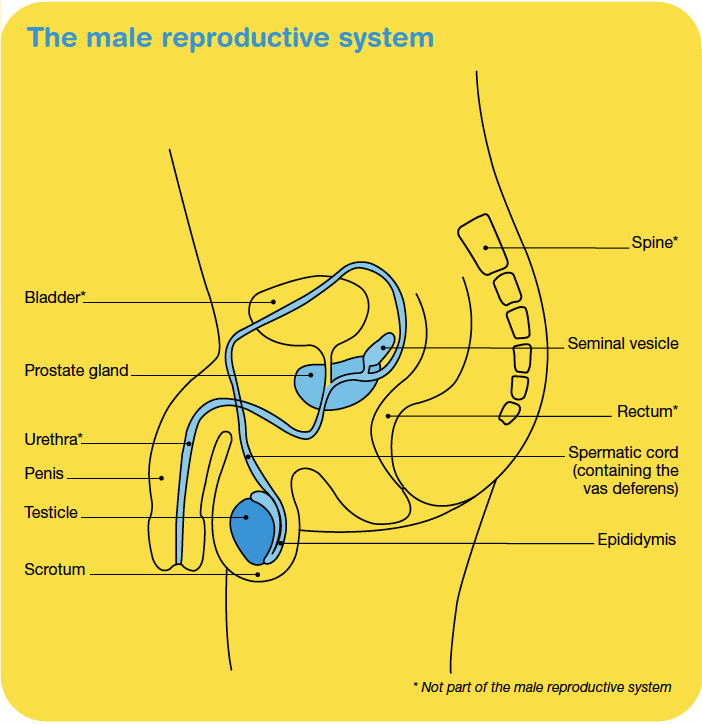

The testicles are part of the male reproductive system, which also includes the penis, prostate and a collection of tubes that carry sperm. The testicles are also called testes (or a testis, if referring to one).

The testicles produce and store sperm. They also produce the sex hormone testosterone, which is responsible, among other functions, for the development of facial hair, a deeper voice and increased muscle mass, as well as sexual drive (libido).

Shape and position in the body

The testicles are two small egg‑shaped glands that sit in a loose pouch of skin called the scrotum which hangs behind the penis. A tightly coiled tube at the back of each testicle called the epididymis stores immature sperm. The epididymis connects the testicle to the spermatic cord, which runs through the groin region into the pelvis and contains blood vessels, nerves, lymph vessels and a tube called the vas deferens. The vas deferens carries sperm from the epididymis to the prostate gland.

Ejaculation

When an orgasm occurs, millions of sperm from the testicles move through the vas deferens. The sperm then join with fluids produced by the prostate and seminal vesicles to make semen. Semen is ejaculated from the penis through the urethra during sexual orgasm.

The lymphatic system helps to protect the body against disease and infection. Working like a drainage system, it removes lymph fluid from body tissues back into the blood. It is made up of a network of thin tubes called lymph vessels connected to groups of small, bean-shaped lymph nodes. Usually, lymph fluid from the testicles drains into lymph nodes in the abdomen (belly).

How common is testicular cancer?

Testicular cancer is not common, but it is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among young men aged 20–39 (apart from common skin cancers). In Australia, about 960 men are diagnosed with testicular cancer each year, accounting for about 1% of all cancers in men.

Learn more about cancer statistics and trends

Types of testicular cancer

The most common testicular cancers are called germ cell tumours. There are two main types:

- Seminoma tumours – tend to develop more slowly than non-seminoma tumours. They usually occur between the ages of 25 and 45, but can also occur in older people.

- Non-seminoma tumours – tend to develop more quickly than seminoma cancers and are more common in people in their late teens and early 20s. There are four main subtypes of non-seminoma tumours including teratoma, choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumour and embryonal carcinoma.

Other tumours

Mixed tumours

Sometimes testicular cancer can include a mix of seminoma cells and non-seminoma cells, or a combination of the different subtypes of non-seminoma cells (mixed tumours). When there are seminoma and non-seminoma cells mixed together, doctors treat the cancer as if it were a non-seminoma cancer.

Stromal tumours

A small number of testicular tumours start in cells that make up the supportive (structural) and hormone-producing tissue of the testicles. These are called stromal tumours. The two main types are Sertoli cell tumours and Leydig cell tumours. They are usually benign and are removed by surgery. Other types of cancer, such as lymphoma, can also involve the testicles.

Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS)

Most testicular cancers begin as a condition called germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS). This was previously called intratubular germ call neoplasia (ITGCN). In this condition, the cells are abnormal, but they haven’t spread outside the area where the sperm cells develop. GCNIS is not cancer but it may develop into cancer after many years.

GCNIS has similar risk factors to testicular cancer. It is hard to diagnose because there are no symptoms and it can only be found by testing a tissue sample. Once diagnosed, some cases of GCNIS will be carefully monitored. Other cases will be treated with radiation therapy or with surgery to remove the testicle.

Risk factors

The causes of testicular cancer are unknown, but certain factors may increase the risk of developing it, including:

- Personal history – If you have previously had cancer in one testicle, you are more likely to develop cancer in the other testicle. Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) is also a risk factor.

- Undescended testicles – Before birth, testicles develop inside the abdomen. By birth, or within the first six months of life, the testicles should move down into the scrotum. If the testicles don't descend by themselves, doctors perform an operation to bring them down. Although this reduces the risk of developing testicular cancer, people born with undescended testicles are still more likely to develop testicular cancer than those born with descended testicles.

- Family history – If your father or brother has had testicular cancer, you are slightly more at risk of cancer. Family history is only a factor in a small number (about 2 per cent) of people who are diagnosed with testicular cancer.

- Infertility – Having difficulty conceiving a baby (infertility) can be associated with testicular cancer.

- HIV and AIDS – There is some evidence that people with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) have an increased risk of testicular cancer.

- Physical features – Some people are born with an abnormality of the penis called hypospadias. This causes the urethra to open on the underside of the penis, rather than at the end. People with this condition are at increased risk of developing testicular cancer.

- Cannabis use - There is some evidence linking regular cannabis use with the development of testicular cancer.

- Intersex variations - The risk of testicular cancer is higher in people with some intersex variations, such as partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, particularly when the testicles remain in the abdomen.

Symptoms

In some people, testicular cancer does not cause any noticeable symptoms, and it may be found during tests for other conditions. When there are symptoms, the most common ones include a swelling or a lump in the testicle (often painless) or a change in a testicle’s size or shape.

These symptoms don’t necessarily mean you have testicular cancer. They can be caused by other conditions, such as cysts, which are harmless lumps in the scrotum. If you find a lump, it is important to see your doctor for a check-up.

Occasionally, testicular cancer may cause other symptoms such as:

- a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum

- a feeling of unevenness between the testicles

- pain or ache in the lower belly (lower abdomen), testicle or scrotum

- enlargement or tenderness of the breast tissue

- back pain

- stomach-aches.

Health professionals

Your general practitioner (GP) will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist called a urologist who will arrange further tests. If testicular cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options.

Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see various health professionals which may include a fertility specialist, medical oncologist, anaesthetist and psychologist, who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Understanding Testicular Cancer

Download our Understanding Testicular Cancer booklet to learn more.

Download now

Expert content reviewers:

Dr Benjamin Thomas, Urological Surgeon, The Royal Melbourne Hospital and The University of Melbourne, VIC; A/Prof Ben Tran, Genitourinary Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and The University of Melbourne, VIC; Dr Nari Ahmadi, Urologist and Urological Cancer Surgeon, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; Helen Anderson, Genitourinary Cancer Nurse Navigator, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD; Anita Cox, Youth Cancer – Cancer Nurse Coordinator, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD; Dr Tom Ferguson, Medical Oncologist, Fiona Stanley Hospital, WA; Dr Leily Gholam Rezaei, Radiation Oncologist, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, NSW; Dheeraj Jain, Consumer; Amanda Maple, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA; Jessica Medd, Senior Clinical Psychologist, Department of Urology, Concord Repatriation General Hospital and Headway Health, NSW.

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Testicular Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2023 edition). This webpage was last updated in August 2023.