For many people, lung cancer is diagnosed at an advanced stage. The main goal of treatment is to manage symptoms and keep them under control for as long as possible. As you may have a number of symptoms, you may be given a combination of treatments.

Your guide to best cancer care

A lot can happen in a hurry when you’re diagnosed with cancer. The guide to best cancer care for lung cancer can help you make sense of what should happen. It will help you with what questions to ask your health professionals to make sure you receive the best care at every step.

Read the guide

Breathlessness

Many people with lung cancer have difficulty breathing and shortness of breath (dyspnoea) before or after diagnosis. These can occur for several reasons, such as the cancer itself and a reduction in lung function, a decrease in fitness level due to reduced physical activity or a build-up of fluid between the linings of the lung (pleural effusion).

Types of surgery that can help improve this symptom include a pleural tap to drain the fluid, pleurodesis to stop fluid building up again and an indwelling pleural catheter. You may also be referred to a pulmonary rehabilitation course to learn about how to manage breathlessness, which will include exercise training, breathing techniques and tips for pacing yourself.

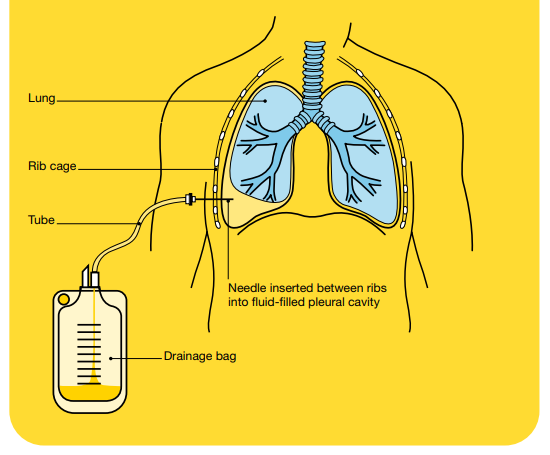

Having a pleural tap

For some people, fluid may build up in the space between the two layers of thin tissue covering the lung (pleural cavity). This is called pleural effusion and can put pressure on the lung, making it hard to breathe. A pleural tap can relieve this symptom. The procedure is also known as pleurocentesis or thoracentesis.

To drain the fluid, your doctor or radiologist numbs the area with a local anaesthetic and inserts a hollow needle between your ribs into the pleural cavity. The fluid can then be drained, which will take about 30–60 minutes. You don't usually have to stay overnight in a hospital after a pleural tap. A sample of the fluid is sent to a laboratory for testing.

Pleurodesis

Pleurodesis means closing the pleural cavity. Your doctors might recommend this procedure if the fluid builds up again after you have had a pleural tap. It may be done by a thoracic surgeon or respiratory physician in one of two ways, depending on how well you are and your preferences:

VATS pleurodesis

This method uses a type of keyhole surgery called video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). You will be given a general anaesthetic, then a tiny video camera and operating instruments will be inserted through small cuts in the chest. After all fluid has been drained, the surgeon then puffs some sterile talcum powder into the pleural cavity. This causes inflammation that helps fuse the two layers of the pleura together and prevents fluid from building up again.

Bedside talc slurry pleurodesis

If you are unable to have a general anaesthetic, a pleurodesis can be done under local anaesthetic while you're in bed. A small cut is made in the chest, then a tube is inserted into the pleural cavity. Fluid can be drained through the tube into a bottle. Next, talcum powder mixed with salt water (a "slurry") is injected through the tube into the pleural cavity. To help distribute the talc slurry throughout the pleural cavity, nurses will help you move into various positions for about 10 minutes at a time. The entire process takes about an hour.

Pleurodesis usually requires a hospital stay of two or three days. After the procedure, some people experience a burning pain in the chest for 24-48 hours, but this can be eased with medicines.

Indwelling pleural catheter

An indwelling pleural catheter is a small tube used to drain fluid from around the lungs. It may be offered to people who repeatedly experience a build-up of fluid in the pleural cavity that makes it hard to breathe and who are unable to or prefer not to have pleurodesis.

Using local anaesthetic, the doctor inserts the catheter through the chest wall into the pleural cavity. One end of the tube remains inside the chest, and a small length remains outside the body for drainage. This end is coiled and tucked under a small dressing.

When fluid builds up and needs to be drained (usually once or twice a week), the end of the catheter is connected to a small bottle. You can manage the catheter at home with the help of a community nurse. Your family or a friend can also be taught how to clear the drain.

Improving breathlessness at home

It can be distressing to feel short of breath, but a range of simple strategies and treatments can provide some relief at home, including:

- Treating other conditions – other conditions, such as anaemia or a lung infection, may also make you feel short of breath, and these can often be treated.

- Sleep in a chair – use a recliner chair to help you sleep in a more upright position.

- Ask about medicines – talk to your doctor about medicines, such as a low dose of morphine, to ease breathlessness. Make sure your chest pain is well controlled, as pain may stop you breathing deeply.

- Check if equipment could help – to improve the capacity of your lungs, you can blow into a device called an incentive spirometer. You may be able to use an oxygen concentrator at home to deliver oxygen to your lungs, or a portable oxygen cylinder for outings. If you have a cough or wheeze, you may benefit from a nebuliser, a device that delivers medicine into your lungs.

- Modify your movement – some types of gentle exercise can help but check with your doctor first.

- Relax on a pillow – lean forward on a table with an arm crossed over a pillow to allow your breathing muscles to relax.

- Create a breeze – use a fan to direct a cool stream of air across your face if you feel short of breath when you're not exerting yourself. Sitting by an open window may also help.

- Find ways to relax – listen to a relaxation recording or learn other ways to relax. Some people find breathing exercises, acupuncture and meditation helpful.

Pain

Pain can be a symptom of lung cancer, but it can also be a side effect of treatment. If pain is not controlled, it can affect your wellbeing and how you cope with treatments.

There are different ways to control pain. Aside from medicines, various procedures can manage fluid build-up that is causing pain. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy can reduce pain by shrinking a lung tumour. Surgery may help treat pain from bones, for example, if the cancer has spread to the spine and is pressing on nerves (nerve compression).

Poor appetite and weight loss

Some people stop feeling interested in eating and lose weight even before lung cancer is diagnosed. These symptoms may be caused by the disease itself, or by nausea, difficulty swallowing, breathlessness, or feeling down.

Eating well will help you cope better with day-to-day living, treatment and side effects, and improve your quality of life. You may find it useful to talk to a dietitian who is experienced in treating people with cancer. A dietitian can help you find foods that you can manage and can recommend protein drinks and other supplements if needed.

Fatigue

It is common to feel very tired during or after treatment, and you may lack the energy to carry out day-to-day activities. Fatigue for people with cancer is different from tiredness, as it may not go away with rest or sleep. You may lose interest in things that you usually enjoy doing or feel unable to concentrate on one thing for very long.

Sometimes fatigue can be caused by a low red blood cell count, the side effects of drugs or a sign of depression and can be treated. There are also many hospital and other programs available to help you manage fatigue.

Difficulty sleeping

Getting a good night's sleep is important for maintaining your energy levels, reducing fatigue, and improving mood. Difficulty sleeping may be caused by pain, breathlessness, anxiety or depression. Some medicines can also disrupt sleep. If you already had sleep problems before the lung cancer diagnosis, these can become worse.

Your medicines may need adjusting or sleep medicines may be an option. You may also consider seeing a counsellor if you feel anxious or depressed.

Getting a better night's sleep

- Try to do some gentle physical activity every day as this will help you sleep better. Talk to a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist, who can tailor an exercise program, and an occupational therapist, who can suggest equipment to help you move safely.

- Limit or cut out the use of alcohol, caffeine, nicotine and spicy food.

- Avoid watching television or using a computer, smartphone or tablet, before bed, as their light tells your body it’s time to wake up.

- Follow a regular routine before bed and set up a calm sleeping environment. Ensure the room is dark, quiet and a comfortable temperature.

- Practice mindfulness and listen to a meditation recording or gentle relaxation music.

- Listen to our Sleep and Cancer podcast episode.

Understanding Lung Cancer

Download our Understanding Lung Cancer booklet to learn more.

Download now

Expert content reviewers:

A/Prof Nick Pavlakis, President, Australasian Lung Cancer Trials Group, President, Clinical Oncology Society of Australia, and Senior Staff Specialist, Department of Medical Oncology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW; Dr Naveed Alam, Thoracic Surgeon, St Vincent’s Private Hospital Melbourne, VIC; Prof Kwun Fong, Thoracic and Sleep Physician and Director, UQ Thoracic Research Centre, The Prince Charles Hospital, and Professor of Medicine, The University of Queensland, QLD; Renae Grundy, Clinical Nurse Consultant – Lung, Royal Hobart Hospital, TAS; A/Prof Brian Le, Director, Palliative Care, Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre – Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and The Royal Melbourne Hospital, and The University Of Melbourne, VIC; A/Prof Margot Lehman, Senior Radiation Oncologist and Director, Radiation Oncology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD; Susana Lloyd, Consumer; Caitriona Nienaber, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA; Nicole Parkinson, Lung Cancer Support Nurse, Lung Foundation Australia.

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Lung Cancer - A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends (2020 edition). This webpage was last updated in June 2021.