What is bone cancer?

Bone cancer can develop as either a primary or secondary cancer and these two types are different.

- Primary bone cancer means that the cancer starts in a bone. It may develop on the surface, in the outer layer or from the centre of the bone. As a tumour grows, cancer cells multiply and destroy the bone. If left untreated, primary bone cancer can spread to other parts of the body. Primary bone cancer is also known as bone sarcoma.

- Secondary (metastatic) bone cancer means that the cancer started in another part of the body, such as the breast or lung, and has spread to the bones.

The bones

A typical healthy adult has over 200 bones, which:

- support and protect internal organs

- are attached to muscles to allow movement

- contain bone marrow, which produces and stores new blood cells

- store proteins, minerals and nutrients, such as calcium.

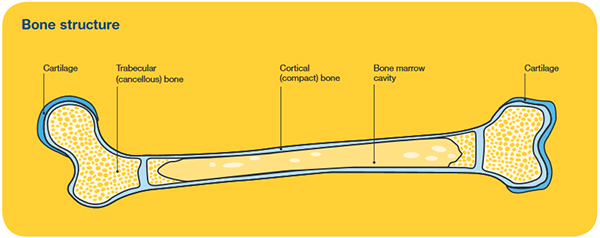

The bones are made up of different parts, including a hard outer layer (known as cortical or compact bone) and a spongy inner core (known as trabecular or cancellous bone), where bone marrow is found. Cartilage is the tough material at the end of each bone that allows one bone to move against another. This meeting point is called a joint.

How common is primary bone cancer?

Bone cancer is rare. About 250 Australians are diagnosed with primary bone cancer each year. It affects people of all ages, but is most often seen in people aged 10–25 and over 50. If it develops later in life, it may be linked to another bone condition.

Your guide to best cancer care

A lot can happen in a hurry when you’re diagnosed with cancer. The guide to best cancer care for sarcoma (bone and soft tissue tumours) can help you make sense of what should happen. It will help you with what questions to ask your health professionals to make sure you receive the best care at every step.

Please note: work is currently underway to refresh the guide to best cancer care for sarcoma.

Read the guide

Types of primary bone cancer

There are more than 30 types of primary bone cancer. The most common types include:

Osteosarcoma (about 35% of bone cancers)

- starts in cells that grow bone tissue

- often affects the arms, legs and pelvis, but may occur in any bone

- occurs in children and young adults with growing bones and older people in their 70s and 80s

- most are high-grade tumours.

Chondrosarcoma (about 30% of bone cancers)

- starts in cells that grow cartilage

- often affects the bones in the upper arms and legs, pelvis, ribs and shoulder blade

- most often occurs in middle-aged and older people

- slow-growing form of cancer that rarely spreads to other parts of the body

- most are low-grade tumours.

Ewing sarcoma (about 15% of bone cancers)

- affects cells in the bone or soft tissue that multiply rapidly and is often associated with a large lump

- often affects the pelvis, legs, ribs, spine, upper arms

- common in children and young adults

- are all high-grade tumours.

Some types of cancer affect the soft tissues around the bones. These are known as soft tissue sarcomas, and may be treated differently. For more details, talk to your doctor or call Cancer Council on 13 11 20.

What are the risk factors?

The causes of most bone cancers are unknown, but some factors that increase the risk include:

Previous radiation therapy (radiotherapy)

Radiation therapy to treat cancer increases the risk of developing bone cancer. The risk is higher for people who have high doses of radiation therapy at a young age. Most people who have radiation therapy will not develop bone cancer.

Other bone conditions

Some people who have had Paget’s disease of the bone, fibrous dysplasia or multiple enchondromas are at higher risk of developing bone cancer. Some studies also suggest that people who have had a soft tissue sarcoma have an increased risk of developing bone cancer.

Genetic factors

Some inherited conditions such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome increase the risk of bone cancer. People with a strong family history of certain types of cancer are also at risk. Most bone cancers are not hereditary. Some people develop bone cancer due to genetic changes that happen during their lifetime, rather than inheriting a faulty gene.

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptom is strong pain in the affected bone or joint. The pain gradually becomes constant and doesn’t improve with mild pain relievers such as paracetamol. It may be worse at night or during activity. Other symptoms can include:

- swelling over the affected part of the bone

- stiffness or tenderness in the bone

- problems with moving around, for example, an unexplained limp

- loss of feeling in the affected limb

- unexplained fractured bone

- unexplained weight loss

- tiredness.

Most people who have these symptoms do not have bone cancer. If you have symptoms for more than two weeks, you should see your general practitioner (GP).

Diagnosis

If you are experiencing symptoms that could be caused by bone cancer, your doctor will take your medical history and perform a physical examination. Bone cancer can be difficult to diagnose and it is likely that you will have some of the following tests:

- x-rays – painless scans of the bones, which can reveal bone damage or the creation of new bone.

- blood tests – to help check your overall health.

- CT or MRI scans – a special computer used to scan and create pictures to highlight any bone abnormality.

- PET scan – you will be injected with a small amount of radioactive glucose solution to highlight any cancerous areas on the scan.

- bone biopsy – removes some cells and tissues from the outer part of the affected bone for examination under a microscope. The biopsy may be done in one of two ways. In a core biopsy, a local anaesthetic is used to numb the area, then a thin needle is inserted into the bone under CT guidance to take a sample. In an open or surgical biopsy, the surgeon will cut through the skin under general anaesthesia to remove a piece of bone.

If Ewing’s sarcoma is suspected, you will have a procedure to examine cells from the inner part of the affected bone. A thin needle is used to remove a sample of fluid (aspirate) from the bone marrow.

Selecting the bone site to biopsy

A bone biopsy is a highly specialised test. It is best that the biopsy is done at a specialist treatment centre, preferably where you would be treated if it is cancer. The site to biopsy must be carefully chosen so it doesn’t cause problems if further surgery is needed. It is important that a bone biopsy is performed by a doctor who is an expert in bone cancer. This also helps ensure the sample is useful and reduces the risk of the cancer spreading.

Staging primary bone cancer

Many cancers are staged using a system that divides them into four stages. But bone cancer is different. It is usually divided into localised or advanced. Ask your doctor to explain the stage of cancer to you.

- Localised - The cancer contains low-grade cells; found in the bone in which it started. It can be removed by surgery (resectable) or not removed completey (non-resectable).

- Advanced (metastatic) - The cancer is any grade and has spread to other parts of the body (e.g. the lungs).

Grading

Grading describes how quickly a cancer might grow.

- Low grade – the cancer cells look similar to normal cells. They are usually slow-growing and less likely to spread.

- High grade – the cancer cells look very abnormal. They grow quickly and are more likely to spread.

Understanding Primary Bone Cancer

Download our Understanding Primary Bone Cancer fact sheet to learn more.

Download now

Expert content reviewers:

Dr Richard Boyle, Orthopaedic Oncology Surgeon, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; Dr Sarat Chander, Radiation Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; James Hyett, Consumer; Rebecca James, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA; Dr Warren Joubert, Senior Staff Specialist Medical Oncology, Division of Cancer Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD; Kristyn Schilling, Clinical Nurse Consultant – Cancer Outreach Program, St George Hospital, NSW; Prof Paul N Smith, Orthopaedic Surgeon, Orthopaedics ACT.

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Primary Bone Cancer - A guide for people affected by cancer (2019 edition). This webpage was last updated in May 2021.