What is lymphoedema?

Lymphoedema is swelling (oedema) that develops when lymph fluid builds up in the tissues under the skin or sometimes deeper in the abdomen (belly) and chest areas. This happens because the lymphatic system is not working properly. It usually occurs in an arm or leg, but can also affect other parts of the body, such as the neck.

Lymphoedema can be either primary, when the lymphatic system has not developed properly, or secondary, following treatment for cancer. It can affect people at any time – during active cancer treatment, after treatment or in remission. It can also develop while you’re living with advanced cancer or during palliative treatment.

Lymphoedema can occur months or years after treatment and usually develops slowly.

The lymphatic system

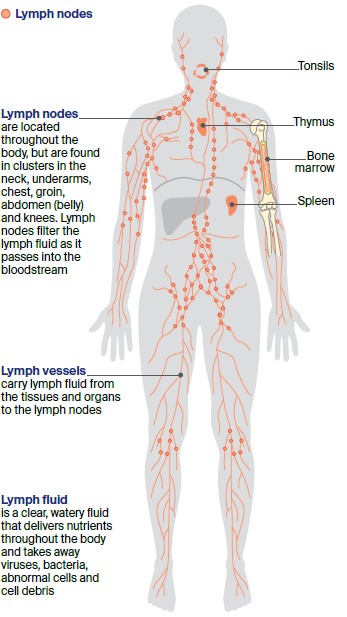

The lymphatic system is part of both the circulatory and immune systems. It consists of:

- Lymph vessels – a large network of thin tubes found throughout the body that carry lymph fluid from our tissues, organs and structures to the lymph nodes.

- Lymph fluid – this normally clear fluid travels to and from the tissues in the body, carrying nutrients and taking away bacteria, viruses, abnormal cells and cell debris.

- Lymph nodes (glands) – small, bean-shaped structures found along the lymph vessels. Lymph nodes are located throughout the body, including in the neck, underarms, chest, abdomen and groin. The lymph nodes filter lymph fluid as it passes through the body, before emptying most of the fluid into the bloodstream.

- Other lymph tissue – found in other parts of the body including the spleen, bone marrow, thymus and tonsils.

The lymph fluid, lymph nodes and lymph tissue contain white blood cells called lymphocytes, which help protect the body against disease and infection.

How common is lymphoedema?

Lymphoedema can occur following treatment for many different cancers. There is little statistical information about how common lymphoedema is following cancer treatment, and the incidence differs for each cancer type.

However, one Australian study estimated that lymphoedema occurs in over 20% of all cancer patients treated for gynaecological (vulvar/vaginal, ovarian, uterine and cervical), breast, prostate cancers or melanoma.

Signs and symptoms

Early intervention

Finding lymphoedema before you notice any signs can reduce the risk of developing swelling. If you are at risk of lymphoedema, ask your treatment team if regular screening check-ups are recommended for you and available near where you live. Early detection and early intervention using education, compression garments and exercise helps to reduce the impact of lymphoedema.

Early warning signs

Taking action quickly can reverse mild lymphoedema and help reduce the risk of developing severe lymphoedema. As soon as you notice any warning signs in the affected area, it’s important to see your lymphoedema practitioner or doctor. Early warning signs include:

- feeling of tightness, heaviness or fullness

- aching in the affected area

- swelling that comes and goes or is more noticeable at the end of the day (or on waking for head and neck cancer)

- clothing, shoes or jewellery feeling tighter than usual

- not being able to fully move the affected limb

- pitting of the skin (when gentle pressure leaves an indent on the skin).

Leaving lymphoedema untreated

If left untreated, lymphoedema can progress and cause a range of problems including:

- trouble moving around and doing your usual activities

- discomfort and sometimes pain

- difficulty fitting into clothes or shoes

- an increased risk of infections

- further hardening of the skin

- lymph fluid leaking from the skin (known as lymphorrhoea)

- very rarely, the development of lymphangiosarcoma, a soft tissue cancer.

Risk factors

Whether or not you develop lymphoedema after treatment for cancer depends on the location of the cancer, its stage and the type of treatment. While the risk is lifelong, most people who are at risk never develop lymphoedema. Some factors increase the risk:

- surgery to remove lymph nodes – the more nodes removed, the greater the risk of developing lymphoedema

- radiation therapy

- taxane-based chemotherapy drugs

- an infection in the limb at risk of developing lymphoedema

- carrying extra body weight (overweight or obesity)

- injury of the lymphatic system – for example, a tumour growing near a lymph node or vessel can block the flow of lymph fluid

- underlying primary lymphoedema

- inflammatory disorders such as arthritis

- not being able to move around easily.

Reducing your risk

There are several things you can do to help reduce your risk of developing lymphoedema after treatment. If you notice changes in the affected part of your body, see your doctor immediately.

Use the affected area normally

- Don’t try to protect the affected limb by limiting its movement – moving the limb normally will keep the lymph fluid flowing.

- Avoid repeated heavy lifting that may result in strain or injury, such as moving heavy boxes or furniture. This does not include exercise or strength (resistance) training.

- Avoid pressure from clothing, underwear and jewellery.

Look after your skin

- Keep your skin clean. Wash with a pH-neutral soap and avoid scented products.

- Moisturise your skin every day. Dry and irritated skin is more likely to tear and break.

- Protect your skin and cuticles – don't cut your cuticles during nail care; wear gloves for gardening, housework and handling pets; use insect repellent to prevent insect bites; avoid cutting or burning your skin when cooking; wear protective clothing, a broad-brimmed hat, sunglasses and sunscreen when in the sun.

- Seek medical help urgently if you notice redness, heat, pain or think you may have a skin infection.

Exercise regularly

- Keep physically active to help the lymph fluid flow.

- Do regular exercise such as swimming, yoga, bike riding, aquarobics, walking or running. Gardening and housework also count as exercise.

- It’s okay to do resistance training – increase the weight and intensity gradually. Be guided by how your limb responds, and cool down slowly.

- Start any exercise slowly and build-up gradually.

- Visit an accredited exercise physiologist or physiotherapist to develop an exercise program.

See Exercise and Cancer for more information.

Maintain a healthy body weight

- Aim to stay in a healthy weight range. Carrying extra weight can be a risk factor for developing lymphoedema.

- Eat a variety of nutritious food each day – see Nutrition and Cancer for more information.

Tips for travelling

Travel – by plane, train, bus or car – has not been shown to increase the risk of lymphoedema. Even so, you may choose to take simple precautions while travelling like wearing loose-fitting clothing, moving regularly and drinking plenty of water. People with lymphoedema, or who have had lymph nodes removed as part of cancer treatment, may be advised to wear a compression garment during long-distance travel. Talk to your lymphoedema practitioner or doctor before you go.

Recognising and managing infections

If lymph fluid can’t drain properly, bacteria can multiply and an infection may start in the affected area or sometimes more generally in the body. People with lymphoedema are at higher risk of getting a serious infection known as cellulitis. Signs of cellulitis include redness, painful swelling, warm skin and fever, and feeling generally unwell.

See your doctor immediately, as antibiotics may be necessary. Talk to your doctor about an 'in case' prescription for antibiotics, so you can start antibiotics as soon as you notice symptoms. If you have cellulitis several times during the year, taking antibiotics for an extended period may help.

Treating symptoms early will improve management of cellulitis. Having one episode of cellulitis increases the risk of further infections.

Diagnosis and staging

Your practitioner will ask about your medical history and assess the level of swelling and any pitting, thickening or damage to the skin. The size of the affected limb will be compared to the other limb, and any differences assessed.

If lymphoedema is diagnosed, it will be staged from 0 (least severe) to 3 (most severe). All stages of lymphoedema need ongoing treatment and care.

Lymphoedema practitioners

Lymphoedema usually requires care from a range of health professionals, including lymphoedema practitioners.

Lymphoedema practitioners may be an occupational therapist, physiotherapist or nurse with specialist training in treating and managing lymphoedema. They assess people with lymphoedema, develop treatment plans, prescribes compression garments, and provides ongoing treatment and care.

They may work as part of a lymphoedema service in a public or private hospital or in private practice.

Find a practitioner

Treatment and management

The aim of treatment is to improve the flow of lymph fluid through the affected area. This will help reduce swelling and improve the health of the swollen tissue, lowering risk of infection, making movement easier and more comfortable, and improving wellbeing.

Mild lymphoedema (stages 0-1) is usually managed with exercise, skin care and compression therapy. Moderate or severe lymphoedema (stages 2–3) usually needs complex lymphoedema therapy (CLT). Less commonly, you may have laser treatment, lymph taping and surgery.

Lymphoedema treatments

Skin care

It is important to keep your skin in good condition to prevent infections.

Exercise

Any physical activity – such as walking and/or strength (resistance) training – can help reduce the severity of lymphoedema. Water-based exercise can be helpful as it provides support and compression.

Aim for about 150 minutes of moderate exercise each week. Exercise may need to be modified if certain movements make symptoms worse. If you usually wear a compression garment, you should also wear it while exercising. A lymphoedema practitioner, exercise physiologist or physiotherapist can design an exercise program for you.

Massage therapy

Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) – This is a specialised type of massage to the affected area that moves fluid towards lymph nodes that are draining normally. It must be performed by a lymphoedema practitioner.

Simple lymphatic drainage (SLD) – This is a simplified form of MLD, which your lymphoedema practitioner may teach you or a carer to do daily. Research into how well MLD and SLD work in managing lymphoedema is ongoing.

Compression therapy

Compression therapy involves applying different levels of pressure to the affected area to reduce and contain swelling, and soften any thickened tissue. Compression for the treatment of lymphoedema needs to be used on an ongoing basis. If stopped, the swelling will usually return.

Not everyone with lympheodema can have compression therapy, as it can be dangerous for people with a range of conditions.

There are different ways to apply compression. Bandages and wraps are used to stimulate the lymph fluid, remove the fluid and reduce swelling:

- applied by a trained lymphoedema practitioner

- often used in intensive treatment (called CLT)

- uses non-elastic bandages or wraps and secured with Velcro

- changed regularly as the swelling reduces

- worn day and night.

Compression garments:

- are used to maintain improvements

- must be professionally fitted to ensure the pressure and fit are correct

- self-applied (you put them on yourself)

- worn during the day as soon as possible after getting up – you may wear a lighter garment at night

- can be off-the-shelf or custom-made

- may be a stocking (leg), sleeve (arm), glove/gauntlet (hand), bra/singlet/vest (breast or chest), leotard (trunk), bike shorts with padding, scrotal supports (genitals), or head and neck garment

- available in different skin tones

- ask your lymphoedema practitioner whether you should wear a garment during airplane travel.

Intermittent pneumatic compression (often called a pump)

A compression pump may be used for people who find it difficult to move around or to perform SLD. This machine inflates and deflates a plastic garment placed around the affected area to stimulate lymphatic fluid. You may need to have MLD or SLD before using the pump.

The pump can be used at home but it’s important that a trained practitioner shows you how to use the pump and adjust the pressure to your needs. You can buy or hire a pump to use at home.

Complex lymphoedema therapy (CLT)

For most people, CLT helps control the symptoms of lymphoedema. It includes a treatment phase and a maintenance phase. During the treatment phase, a lymphoedema practitioner provides a combination of regular skin care, exercises, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), and compression bandaging.

It may take a few days or up to several weeks to reduce the swelling and then you will be fitted with a compression garment. You will also be taught how to take over the management of your lymphoedema. During the maintenance phase, you continue to look after your skin and exercise regularly.

Wearing the compression garments prescribed by your practitioner will help maintain the improvements made in the treatment phase. It is recommended that you see your lymphoedema practitioner for regular reviews, but this may vary depending on your circumstances.

Laser treatment

This treatment uses low-level laser to target cells in the lymphatic system. This may reduce the volume of lymph fluid in the affected area, any thickening of the skin and pain.

Your lymphoedema practitioner will use a handheld device or a larger scanner to apply infra-red-light beams to the affected area. You will not feel any heat. There is some evidence that laser treatment works well when used with lymphatic drainage and compression therapy. Research is still continuing into this treatment.

Lymph taping

Some early research suggests that a special tape (called kinesiology tape) can help lymph fluid drain from the affected area. The tape is different from strapping tape, and your lymphoedema practitioner will tell you whether this could be part of your management plan.

Surgery

Most people are able to manage lymphoedema with CLT, but surgery may be an option when lymphoedema doesn’t respond to other treatments or you are not satisfied with standard treatment.

To work out whether surgery is right for you, your specialist will consider the extent of the swelling, how often you get infections and your general health. It is best to have surgery for lymphoedema in a specialist centre.

As with all surgery, there are significant risks involved. These include scarring, nerve damage, blood clots, infection, loss of mobility, further damage to the lymphatic system, and continuing lymphoedema. Most people still need to wear a compression garment after surgery.

Examples of surgery for lymphoedema include:

- Liposuction – In some people, the lymphoedema fluid changes into fatty tissue, but CLT doesn’t reduce the fat. Liposuction removes fat from under the skin of the affected area and the limb will look smaller. It should only be an option when CLT cannot reduce the swelling. This treatment is not a cure for lymphoedema – it’s essential to continue wearing a compression garment.

- Lymphatic reconstruction (anastomosis) – This uses microsurgery to repair or create a new pathway for the lymph fluid to drain out of the area. This technique appears to work better for people with early-stage lymphoedema. Further research on the long-term impact on people who have undergone this surgery is needed.

- Lymph node transfer – This involves transferring healthy lymph nodes from an unaffected area of the body to the affected limb. Further research is required into whether this technique is effective in the long term.

Medicines

There is no proven drug treatment for lymphoedema and some medicines may make it worse. There is little evidence to support taking naturopathic medicines or supplements such as selenium to help reduce lymphoedema symptoms. Talk to your doctor before taking any supplements or medicines to ensure they are not harmful.

Caring for the affected area

If possible, you should:

- keep cool in summer as the heat may make swelling worse – have cold showers, stay indoors during the hottest part of the day, avoid sunburn, and drink plenty of water

- wear clothing and jewellery that fits well and doesn’t put pressure on the affected area

- tell health professionals that you have lymphoedema (or are at risk of lymphoedema) before having blood taken, injections, blood pressure monitoring or other procedures – it may be safe to use the affected arm, but your health professional will discuss this with you.

Coping with lymphoedema

Looking after your wellbeing

Lymphoedema can affect your body and mind, so it’s important to look after your wellbeing. Having lymphoedema can affect how you feel about yourself in several ways.

Some people find it helpful to talk with family and friends, while others seek professional help from a counsellor. You may find it helpful to talk with other people who are dealing with lymphoedema.

Paying for treatment

Treatment for lymphoedema can be expensive. There are options to help with these costs:

- If your GP refers you to a lymphoedema practitioner as part of a Chronic Disease Management Plan, you may be eligible for a Medicare rebate for up to five visits each year.

- Compression garment subsidy schemes are run by all state and territory governments. There are also some federal subsidies through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. These schemes cover some, or all, of the cost of compression garments. People with permanent and significant disability may be eligible for support through the National Disability Insurance Scheme. For more information, visit lymphoedema.org.au.

- If you have private health insurance, check with your provider whether you are entitled to a rebate on compression garments and lymphoedema therapy.

Get financial and legal support.

Understanding Lymphoedema

Download our Understanding Lymphoedema fact sheet to learn more

Download now

Expert content reviewers:

A/Prof Louise Koelmeyer, Director, Australian Lymphoedema Education, Research and Treatment (ALERT) Program, and Associate Professor, Macquarie University, NSW; Prof John Boyages AM, Founding Director and Honorary Professor at the ALERT Program, Macquarie University, NSW; Dr Nicola Fearn, Occupational Therapist and Accredited Lymphoedema Therapist, The Lymphoedema Clinic Wollongong, and Senior Research Officer, St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, NSW; Jennifer Gilbert, Clinical Nurse Consultant – Lymphoedema, Icon Cancer Centre, Chermside, QLD; Megan Howard, Senior Physiotherapist and Lymphoedema Physiotherapist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Caitriona Nienaber, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA; Dr Amanda Pigott, Clinical Specialist Occupational Therapy, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD; Prof Neil Piller, Director, Lymphoedema Clinical Research Unit, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, SA, and Patron, Lymphoedema Association of Australia; Ashlynne Pointon, Consumer; Dr Cathie Poliness, Breast Surgeon, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Tara Redemski, Senior Physiotherapist – Cancer and Blood Disorders, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD.

Page last updated:

The information on this webpage was adapted from Understanding Lymphoedema - A guide for people affected by cancer (2023 edition). This webpage was last updated in September 2023.